Forced to Make a Living:

The Vulnerability of Women Traders in the Thambuttegama Periodic Market, or Pola, in Sri Lanka

Fazeeha Azmi

Introduction

When a child is hungry, it says 'mother I am hungry', it doesn't say 'father I am hungry.' Men do not understand these things. That is why I became a pola trader; I have to feed my children. Still, pola women are looked down upon by the society. There is no other way here for us to survive.[1]

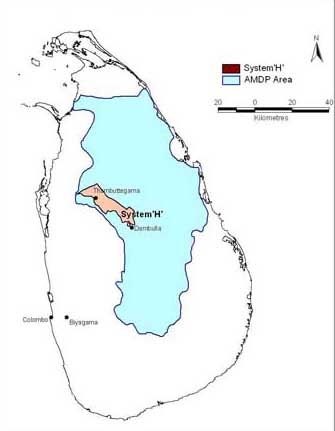

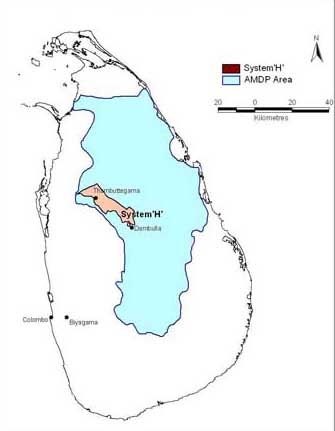

Sri Lanka has made strides towards bridging the gender gap but the counbtry still has a long way to go before women can take control of their own lives. Development policies adopted by the Sri Lankan Government in the recent past have placed a heavy focus on increasing women's economic participation. As a result, more women have gradually entered the labour force since the 1980s. However, a closer look at the situation reveals that Sri Lankan women continue to face gender inequalities, discrimination, exploitative situations and unequal opportunities.[2] This is especially the case in the economic sphere. Jayaweera Swarna notes that although women have increased access to paid employment, they are largely confined to low-paid, casual and marginal income-earning activities.[3] Their presence is high in labour-intensive industries such as the garment and plantation industries, and also among migrant labourers to Middle Eastern countries. Sri Lankan women's participation in the informal sector has also increased since the 1980s. In the informal sector, market trading is one area that provides employment opportunities for impoverished women. Little research has been conducted into women's involvement in periodic markets in rural areas in Sri Lanka or the problems faced by women working in these markets. The present study highlights and discusses the different forms of vulnerability experienced by women pola traders at the Thambuttegama pola, or periodic small market, which is located in System H (one of thirteen administrative systems) of the Accelerated Mahaweli Development Project of Sri Lanka (hereafter referred to as AMDP (see Map 1 below). The study also confirms that pola women's economic participation is merely a survival mechanism rather than one of empowerment.

The Accelerated Mahaweli Development Project of Sri Lanka

The AMDP is one of the largest multi-purpose development project schemes in Sri Lanka aimed at solving the country's socio-economic problems. Implemented in the late 1970s, the scheme aimed

|

|

to resettle 250,000 families, mainly headed by impoverished farmers, in the project area. The plan was based on the assumption that resettling farmers in different administrative units of the project area would improve the agricultural economy by providing irrigation facilities to previously uncultivated and under-cultivated land. The settlers in the AMDP can be grouped into three main categories. These are 1) the original settlers who lived in the area before the commencement of the project, 2) re-settlers or evacuee settlers who were resettled in Mahaweli settlements after losing their properties when dams were constructed under the AMDP, and 3) settlers from different parts of the country who were given land in the AMDP due to landlessness, poverty or political affiliation.[4]

Map 1. Location of the Accelerated Mahaweli Development Project (AMDP) and System H. Map prepared by Swarna Seneviratne, cartographer, Department of Geography, University of Peradeniya, Sri Lanka.

|

The settlement planning of the AMDP was based on the model of central place hierarchy.[5] Thus, in terms of facilitating trade, the planners attempted to develop a more accessible system for the settlers concerned. However, trading activities have also developed spontaneously outside the formal infrastructural process of the AMDP administrative blocks,[6] including in System H where I conducted my research. M.D. Nelson notes that under the trading activities spontaneously developed in the settlements, periodic markets or pola are important features.[7] These periodic markets dominate not only the economic landscape of the settlements, but also the social landscape where many settlers have carved out a niche. In the following section I discuss the nature of pola in both the national and the AMDP contexts. I also discuss the gender ramifications of the 'pola' market activity.

Periodic or pola markets are held on specific days once or twice a week at an allocated place. They are the main marketing channel for farmers to sell surplus production and to buy necessities. Goods sold at the periodic markets reach the consumers in different ways. In some cases, farmers sell their produce directly to consumers. Sometimes agents buy or collect the primary products from the hinterland and sell these on to the pola traders. Occasionally several steps occur before the produce reaches the market. These trading activities create a strong spirit of competition at pola. Periodic markets also serve as sites of social interaction where information, ideas and innovations are disseminated. Pola have long been an important economic and social unit in Sri Lanka's rural areas, although they are also found in urban areas. Pola traders are generally men, unlike the African context where the majority of traders are women.[8] While pola are dominated by men as sellers, buyers at these markets are frequently women and children.

Until the late 1970s, pola sales were mostly confined to agricultural products. Since the 1990s a wide variety of items are sold ranging from cellular phone covers to audio CDs. Goods on sale at the pola are usually separated by type, with different sections being set aside, for example, for vegetables, fruit, dried fish, fresh fish, ready-made clothes, locally made pottery, betel leaves, areca nuts and ornaments. Typically, there are also musicians, singers, beggars, fortune tellers and lottery ticket sellers at a pola in Sri Lanka.

The administration and maintenance of pola is the responsibility of local government authorities in each specific area. While some pola are administered directly by the local authority, others are tendered out to agents who subsequently lease out the stalls. There are also pola traders operating outside the area designated for the leased stalls. These traders, who for various reasons are unable to obtain a stall within the designated market area, are forced to pay a tax to a collector appointed by the local government.

Although there are no time series data on the growth of periodic markets, several studies indicate that the numbers of periodic markets are on rise in rural Sri Lanka.[9] Certainly, there was a dramatic increase after the implementation of the AMDP.[10] This can be related to the spontaneous process of development and social change created by the AMDP scheme. Today, polas have become important in the economy of Mahaweli, where many small farmers sell their limited surplus to people in the hinterland, whose purchasing power is generally low, as well as to buyers from outside the area. Thambuttegama is a pre-Mahaweli township located in System H. (See Map 1.) With the township's incorporation into the AMDP, Thambuttegama flourished and is now a busy business town where wholesale and retail traders of agricultural products meet. After the establishment of the Thambuttegama Dedicated Economic Centre (DEC), pola in the area performed an important role in the collection and distribution of the agricultural products of the region.

My study was confined to the Thambuttegama local administrative unit in System H of the AMDP. I researched women traders from the Thambuttegama pola which is held each Wednesday. As was the case in many places, the pola in Thambuttegama did not have permanent building structures until March 2007. Prior to the construction of permanent stalls, the traders used temporary shelters or huts erected on open ground spaces from where they sold their goods each pola day. Some traders who were unable to secure stalls still continued to operate on pola days but, as mentioned above, they were required to pay tax to the local government authority for the space they occupied.[11] Many traders visited different polas which were conducted on different days of the week in the area. This pattern is called pola rawume or 'pola circuit.'

There has been a significant change in the economic activities undertaken by women in today's AMDP pola markets compared to the activities of women in the Mahaweli settlements of the past. As a survival strategy, many women no longer confine themselves to unpaid or underpaid labour at home or on family farms but now also undertake remunerated work outside the home. In the absence of gainful employment opportunities within the settlements, many migrate to urban areas and to Middle Eastern countries in search of wage labour. However, middle-aged and elderly women, in particular, are often not fortunate enough to find employment through such avenues. In response to increasing economic hardship, poverty and lack of access to productive land or support from the government and their husbands, some of the women who have been forced to remain in Mahaweli settlements have ended up as traders at periodic markets.

Women pola traders participate in an economic activity which is dominated by men and they face specific forms of vulnerability and powerlessness in their domestic, economic and social spheres of life. While compelled to participate in income-earning activities in a male domain to ensure the survival of their families, women pola traders also have the additional burden of meeting the prevailing norms of social obligations towards their families and also to the wider society. To non-pola society, pola women appear to be independent and courageous women with masculine qualities.[12] However, a closer look reveals that they face considerable gender inequalities, discrimination and unequal opportunities, and that they are more vulnerable than men to exploitative situations.

As Christiana Solomon asserts, generally, women who trade at markets are poor.[13] Poverty makes market women vulnerable to a range of disadvantages embedded in the conditions of the social, historical and political environments at both the local and global levels. They are therefore unable to withstand the adverse impacts of the shocks and stresses to which they are exposed. Robert Chambers defines vulnerability as defencelessness, insecurity, and exposure to risk, shocks and stresses, as well as difficulty in coping with such situations.[14] This definition suggests that vulnerability has two sides: one related to the external 'risk aspect,' the other to the internal 'coping capacity' necessary to deal with loss. While emphasising that poverty and vulnerability are different concepts,[15] Chambers also points out that losses can result in economic impoverishment, social dependence, humiliation and psychological harm. Although stresses, shocks and risks can arise from either situations created by human beings or natural calamities, the problems faced by women traders are largely pre-existing in the women's communities. Their ability to withstand or cope with stresses, shocks and risks depends on a range of factors. These include individual or household levels of human and physical assets, levels of production, income and consumption, and, importantly, the ability of individuals or households to diversify their sources of income and consumption to effectively reduce the effects of the risks that they face at any given time. Anju Malhothra and Mark Mather explain that women traders in the pola markets have low skills levels and very limited capital. Hence, few of the women traders have access to formal sector employment opportunities.[16] Others who lack access to land or other property in the settlements try to solve their problems through hard work, the only meagre resource they possess.

Coping capacity varies according to individuals, households and communities. From an ability to cope perspective, gender is an important attribute influencing the coping capacity of women in vulnerable situations. As a socially constructed concept, gender varies across different social contexts with different social norms and customs determining the roles of women and men in the family and community.[17] Since different societies have their own expectations in terms of gender roles, even an individual with a high coping capacity may be prevented by gender norms from exercising this capacity in vulnerable situations. Caroline Moser defines this as 'social control.'[18] Given that social norms are expressed through institutions,[19] such as the family, religion, culture and tradition, media, state policy, legal regulations, education, and the economy, it is not surprising that in the economic sphere certain jobs are assigned as either 'masculine' or 'feminine.' When men take on what are considered to be 'feminine' tasks they are ridiculed.[20] Similarly, if a woman takes on a job normally associated with masculity she is not only considered unfeminine, but she also becomes vulnerable in multiple ways–as will be discussed in greater detail below. There is a strong likelihood that continuous exposure to vulnerabilities generated in this way will eventually dis-empower women. On the other hand it could be argued that if enough women step outside their gender ascription, then more women will be encouraged that it is acceptable. In other words they will become role models.

The concept of empowerment has been approached and described variously focussing on aspects such as agency, participation, control over material and non-material assets, self-confidence and dignity.[21] However, the central concept in these approaches and definitions is 'power.' Although there are number of feminist perspectives on power, the present study draws on the work of Jo Rowlands who classifies four dimensions of power. These dimensions are 1. 'power from within' (psychological power evidenced by factors such as self-confidence, self-esteem and self-respect), 2. 'the power to' (the capacity to take action), 3. 'power with' (the collective forces whereby people cooperate with each other to solve a problem), and 4. 'power over' (the ability to resist force).[22] Rowlands also categorises the experience of empowerment at three different levels, namely the personal level, the collective level and the level of close relationships. She emphasises that each level is important in order to achieve full empowerment. Rowlands argues that personal empowerment involves 'developing a sense of self and individual confidence and capacity, and undoing the effects of internalised oppression.'[23] The relational dimension of empowerment relates to 'developing the ability to negotiate and influence the nature of a relationship and decisions made within it.'[24] The collective dimension of empowerment is defined as 'where individuals work together to achieve a more extensive impact than each could have had alone.'[25] I would argue that the 'personal' dimension of empowerment should be given particular attention as, in certain contexts, it is a pre-requisite for developing relational and collective dimensions of empowerment.[26] At the same time, it is also important to consider what personal, collective and close relationship dimensions of empowerment mean in different socio-economic and cultural contexts and how people, women especially, operating in these specific contexts might be adequately empowered to equitably access the resources of a society.

The field survey was carried out from March to mid-May 2007.[27] In-depth interviews were conducted with fourteen Thambuttegama pola women traders who were from three different types of settlement in System H. Although there are several pola in System H of the AMDP, administrative limitations restricted my research to the Thambuttegama pola. However, this was not a significant problem since this pola had comparatively large numbers of women traders.[28] My research period lasted ten weeks and included both pre-and post-New Year periods.[29] During the field visits, I observed that the pola attracted a large number of customers during the New Year season while the numbers of customers were less at other times of the year.

I interviewed the women pola traders at the pola itself. During my first visits I met the women in the morning either before they unpacked or while they were unpacking their goods. However, since the morning hours were their best trading times, the majority of women said they did not want to be interviewed before noon. Therefore, I used the mornings to make personal observations and conducted interviews in the afternoons. These interviews focused on exploring the potential for economic empowerment of women at pola and the means by which their vulnerabilities might be reduced. In addition to interviewing the pola women, I also held informal discussions with government officers and other key informants. These discussions assisted me in understanding the functions and administration of pola and the constraints and opportunities faced by pola traders generally and by women traders in particular.

The socio-economic backgrounds of the respondents are shown in Table 1 below. This table clearly indicates that the majority of the respondents were middle-aged or elderly, a trend that is apparent also at pola in other parts of the country. In one sense, however, this was an advantage since social and cultural restrictions become less rigid in Sri Lankan rural society as people age.[30] Generally, therefore, a pola woman's status increases with her age. In general, the informants had started to trade at pola after the death of their husbands or after they had been involved in divorce or separation. Since the burden of supporting family members, especially children and other dependents, then fell on these women, they were forced to find a way to supplement the family income.

Table 1. Socio-economic background of the informants

| Respondent no. |

Age |

Marital status |

Number of children |

Employment prior to pola trade |

Education |

| R 1 |

45 |

Divorced |

3 |

Did not work |

Year 9 |

| R2 |

54 |

Divorced |

3 |

Middle East migrant |

Year 5 |

| R3 |

66 |

Married |

7 |

Agricultural labourer |

No schooling |

| R4 |

57 |

Separated |

2 |

Middle East migrant |

GCE (O/L)* |

| R5 |

50 |

Separated and remarried |

4 |

Agricultural labourer |

Year 9 |

| R6 |

58 |

Widow |

6 |

Did not work |

Year 4 |

| R7 |

80 |

Widow |

10 |

Agricultural labourer |

No schooling |

| R 8 |

63 |

Separated |

6 |

Domestic aid |

Year 3 |

| R9 |

67 |

Separated |

7 |

Food seller |

No schooling |

| R10 |

51 |

Married |

5 |

Middle East migrant |

Year 10 |

| R11 |

48 |

Married |

4 |

Garment factory worker |

GCE (O/L) |

| R12 |

50 |

Divorced |

5 |

Did not work |

Year 10 |

| R13 |

63 |

Widow |

7 |

Agricultural labourer |

No schooling |

| R14 |

74 |

Widow |

9 |

Agricultural labourer |

No Schooling |

Source. Field work by author, March 2007–mid-May 2007.

* General Certificate of Education: O Level.

Education has important implications for the socio-economic status and potential of women. However, although the overall literacy rate of Sri Lankan women is the highest for women in the South Asia region,[31] the truth behind this average is relative. Women pola traders, like their counterparts throughout the rural economy, are generally less well educated than urban women. Table 1 shows that the education level of the respondents was relatively low. Most of the women who had attended school had been educated only up to primary level, although 14 percent had completed secondary education. Approximately 35 percent of the women had never been to school. Furthermore, the majority of the women interviewed did not possess any employment skills. This combination of lack of education and lack of employment skills meant that few of the women were able to improve their position by making use of the new employment opportunities created by the national economy or the expanding regional economy. Even for educated women, however, the limited number of jobs in the formal sector was also a problem due to gender role assumptions.

In terms of marital status, only 28 percent of the respondents were currently married with the majority being separated, divorced or widowed. This situation is typical at other pola in the country. The fact that the number of children among older women traders was high compared to those among the middle-aged traders is likely to be related to declining fertility rates in Sri Lanka, especially since the late 1970s.

Most of the women interviewed had previously been employed in marginal sectors of the economy. Some had worked as unpaid family labourers on their paddy land, while others had sought employment only after the death of their husbands. Prior to becoming traders at the pola, 35 per cent of the women had been agricultural labourers. Of the women who had received secondary education, 35 per cent had worked either as housemaids in Middle Eastern countries or in garment factories. The remainder had been engaged in menial jobs with severely limited wage rates. I will discuss how these women responded to an economy in transition, even though they were among the most vulnerable workers in Sri Lanka because of their relative lack of skills and education.

Women in the changing Mahaweli economy

Women and men are positioned in different ways in the local economy of Mahaweli. Since their arrival and incorporation into the AMDP, many Mahaweli women have performed various agricultural tasks in addition to their daily household duties. At the time of my research their main responsibilities were articulated by gender-specific roles, where women were mainly responsible for reproduction and the maintenance of household welfare, while men were responsible for their families' financial needs and activities outside the home.

Since the introduction of open economic policies in the 1970s, considerable changes have occurred in Sri Lanka's economy in terms of employment opportunities in general and for women in particular. The integration of Mahaweli's local economy into regional, national and international economies had considerable negative impact on the socio-economic roles of Mahaweli women.[32] This was because access to land, the main productive resource, was denied to women, against the customary inheritance pattern of the country.[33] Both the establishment of garment factories in the Free Trade Zones (FTZs) closer to Colombo, the capital of Sri Lanka, and the opening of employment opportunities in Middle Eastern countries attracted women workers from many parts of Sri Lanka. Such employment opportunities became accessible to Mahaweli women only after the 1990s. This latter group was left either without jobs or they were compelled to work in low paid, casual and marginal economic activities. For women unable to find employment elsewhere, the expansion or increase in the number of periodic markets in the Mahaweli settlements provided a much needed opportunity for earning an income. One respondent commented on these changes as follows:

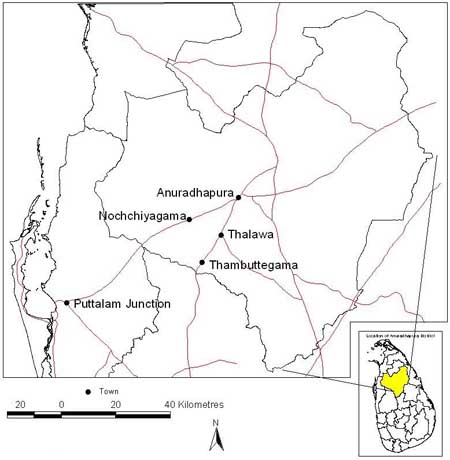

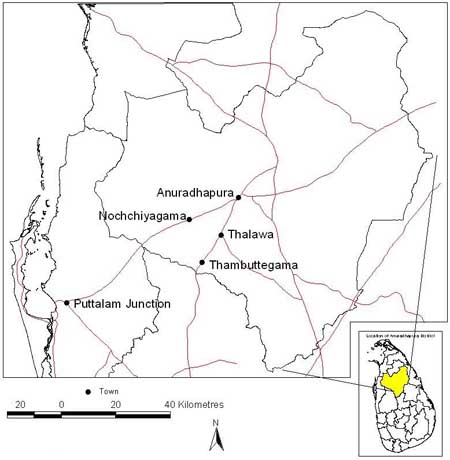

Unlike the past in the Mahaweli area these days you can see a lot of polas. Now you don't have to go to villages to collect vegetables. You can come to the Thambuttegama wholesale market and sell at the pola. On Wednesdays, I trade at Thambuttegama pola and I also trade at Puttalam Junction, Thalawa, Nochiyagama, and Anuradhapura pola. [See Fig. 2 for the location of these sites.] Transport is now easy. If my husband does not have coolie work he also joins me on other pola circuits. There is lorry which comes in the morning close to Thambuttegama wholesale market.[34]

Figure 1. Female traders in Thambuttegame Pola. Photograph taken by author, 4 April 2007.

Figure 1. Female traders in Thambuttegame Pola. Photograph taken by author, 4 April 2007.

|

Since its incorporation into the AMDP, Thambuttegama has developed into a multiple function township. The sudden population influx which accompanied resettlement changed the long established pattern of trade in the area which formerly was based mainly on surplus agricultural products. Following resettlement, however, new trade outlets flourished in Thambuttegama Township. AMDP has sponsored the construction of a network of minor and major roads that connect many previously remote centres, which has further facilitated the development of polas in the area.

Map 2 shows the pola attended by respondents. The recent set-up of the Thambuttegama Economic Centre and Dambulla Dedicated Economic Centre (DDEC) has made pola trading even more attractive,[35] with many women also using these centres to make wholesale purchases of vegetable or fruits for subsequent resale. Although traditionally traders went to villages to collect vegetables and fruit to sell at a pola, added family and community responsibilities mean that this is not always possible for women traders.

Map 2. Pola visited by female traders in Thambuttegama. Map prepared by Swarna Seneviratne, cartographer, Department of Geography, University of Peradeniya, Sri Lanka.

Map 2. Pola visited by female traders in Thambuttegama. Map prepared by Swarna Seneviratne, cartographer, Department of Geography, University of Peradeniya, Sri Lanka.

|

In the past, unpredictable transport arrangements, long distances and few consumers made pola trade very hectic and unattractive to many traders, especially women. However, the creation of the Thambuttegama and Dambulla economic centres has improved these adverse conditions and this has led in turn to a gradual increase in the number of traders. Pola trading has become particularly appealing to many financially weaker women who lack the capital necessary to be self-employed in other ways. During the time of my research it was a common sight to see women who live close to a main road but who are unable to trade at a pola constructing small stalls in front of their houses to sell vegetables or fruit either purchased from the wholesale centres or produced in their home gardens.

Women have also made use of the expansion of the national and global economies to undertake pola trading activities. Free Trade Zones (FTZs) are important economic landscapes created by the process of globalisation and they have provided direct and indirect employment for many Sri Lankans especially in the garment industries. One woman discussed how she retailed clothing goods she was able to buy cheaply from a Free Trade Zone:

I worked in Colombo as a domestic aid. I am very familiar with that area. My employer migrated to a foreign country, so I came back to the village. On my last day in their house, my employer's wife gave me 10,000 Rs to buy some ready-made clothes from a shop close to Biyagama Free Trade Zone to sell in our village. This business gave me lot of confidence. When all my children were married, I started to sell clothes that I buy from Biyagama at pola. Sometimes I would buy clothes from our own village, but these were not made to a good standard or were not in the latest fashion. [36]

Many women and men who lived in the towns located in close proximity to the Free Trade Zones made use of the fabric, or in the local term, 'cut pieces,' disposed of by garment factories, to sew frocks, curtains and bedspreads. Like Respondent 8, some of my informants bought finished clothes from such places and resold these at Thambuttegama pola.

Pola women and multiple vulnerabilities

During my visits to Thambuttegama in 2004, the pola, which was located in the city centre, operated out of temporary structures. However, in 2008, the market looked modern and very large, with permanent buildings and other facilities. During a recent follow-up visit to Thambuttegama, to find out how these new pola structures were operating, I noted an increase in the number of women. These women were selling a range of goods such as vegetables, fruits, food and readymade clothes. Some of them did not have a permanent place in the pola compound and were selling their products outside the market grounds. In order to understand why this was happening, I approached one of the women as she was getting ready to go home after business. She explained as follows:

I have been trading at this pola for the last twenty-four years. I started to sell tea at this pola along with my husband. My husband passed away. Now I am doing this business alone. Earlier, very few women traded at the pola. Even if they traded, most of them did the trading along with their husbands, but during the last fifteen years, the number of female traders has considerably increased. You know, men cannot find employment these days. There are conflicts in families due to this and many families are torn apart. Whoever fights, the family responsibility eventually falls into the hands of women. That is why we can see many female pola traders these days.[37]

Pressured by sub-standard living conditions, personal fate, poverty, landlessness, and unemployment, women in the Mahaweli settlements are forced to seek work outside the home. In addition to the local factors discussed above, the social, economic and political environments of the country during the last three decades have also placed increased burdens on poor women. In the following section I will discuss some of the specific vulnerabilities to which women traders at pola markets were subjected with reference to the data gathered during interviews.

Some of my interviewees articulated the fear that they would be evicted from their trading sites. Two of them expressed their anxieties as follows:

I do not know how long can I survive in this pola. I do not have a permanent stall. Who can pay the rent? It is too high. When they [officers or leasers] chase us, we run. What else could we do?[38]

I am eighty years old. I have been trading at pola since 1962. When my husband was alive, both of us were engaged in pola trade and we had permanent stalls. My husband passed away eighteen years ago. Since then I have not had a permanent stall. I come only to the Wednesday circuit now. Many women at this pola help me. They give me a small space to sell my vegetables. Yet tax collectors force me to pay the rent and they threaten me to vacate the space. I earn a small profit. How can I pay the rent?[39]

Like these two respondents, many women occupy illegal trading spaces and are therefore subjected to harassment by the local government authority or the leaser appointed by the authority. This was a major problem since their tiny profit margins meant that paying tax deprived them of any income at all. Further, women were sometimes deprived of the opportunity to trade. According to some respondents, space allocated to women was often appropriated by men. When this happened, rather than resist, women would cede their places to the men in order to ensure their future survival at the pola.

In order to create the free time to engage in pola trade it was necessary for women to renegotiate domestic tasks with husbands or others in the household. However, not all women were fortunate enough to have supportive males in their families, and, without grown-up daughters or other women upon whom to depend, these women were compelled to work both inside and outside the home. Many confided that they had to attend to their domestic work before they could go to a pola. One, in particular, explained:

I was the youngest female trader at the Thambuttegama pola. I started my business at the age of twenty-three and am still continuing. I divorced my husband when I was pregnant with my youngest daughter. Then I was twenty-one years. As my marriage was due to a love affair which my parents or sibling did not like, I did not have support from my family. I worked as an agricultural labourer for two years. Since the day I divorced my husband I have been doing the household duties alone. I do not ask my children to do household work. I give priority to their education. So I get up early in the morning and do all the household work and go to the pola. I return from the pola and prepare the dinner.[40]

Another respondent was more fortunate, explaining how she negotiated the household duties while she was away at work:

I worked in a garment factory before I became a pola trader. My husband lost one of his legs due to a quarrel in a land dispute. After that I quit the job in the garment factory to take care of him and the children. I ran a small business at home. During that time it was easy for me to manage household duties and the business. I did this business for three years but I could not get the capital back. People buy goods on loan and they never settle. So, I decided to trade at pola. My husband takes care of the children and prepares the meals when I am not at home. During the festival season in April lots of people come to the pola then, so I have to stay at the pola longer than during the other seasons. During those times, my daughters also help my husband with the household duties.[41]

In many rural families, children also perform household work. Girls in the family often help their mothers to take care of younger siblings, carry water and collect fire wood. A similar situation has been noted in the peak agricultural seasons in rural areas.[42] However, some women have no one to help. When I asked one woman trader, who was breast feeding her five month old son while selling fruit, why she brought the infant for the whole day to such a noisy, smelly and unhealthy environment, she replied:

My children are going to school and I chased away my husband as he depends only on my income. I cannot feed him too. I don't have anyone to take care of my son. I have to take him to the pola.[43]

This respondent was representative of many pola women who had to integrate household responsibilities with pola trading. Even if they were living with their husbands, prevailing gender ideologies and patriarchal values[44] concerning household work placed extra burdens on women traders. Some of the women who did not have permanent stalls mentioned the difficulty of securing a good place at the pola because, since they must complete household duties prior to leaving home, they always arrived at the market later than men traders. The extracts given here from the women trader's stories, clearly reveal their double burden of paid and unpaid work. After all the struggles that they faced at home, they had to come to pola. But their struggles did not end and many experienced sexual harassment—as one of my respondents explained:

Being a middle-aged or young female trader at a pola is extremely difficult. I sell breakfast and tea here. Some of them [male traders] are treating me like their own sisters, some are not. So they are approaching me for different purposes, but it depends on how you handle such people. If we are flexible, men make use of the opportunity. Many men at the polas whom I have been trading with have approached me for unwanted things, but I always tell them I am not the type of woman they expect. At Anuradhapura pola, you can see the pola activities going on until night, but I never stay after six in the evening. I don't understand why these men behave like this. I must say, not all men at pola are so. Due to some men, it is women who are affected.[45]

Sexual harassment by male traders was not openly mentioned in my initial interviews. This could have been due to the fact that Sri Lankan society regards women as totally or partially responsible for such situations.[46] However, the presence of sexual harassment was confirmed by the young woman quoted above during my third visit to the pola. Given the largely informal environment, some of the young pola women, especially, appear helpless in the face of what could be described as sexual harassment or exploitation. In contrast, middle-aged and elderly women traders are less vulnerable. Another respondent pointed out that some women had responded positively to men's approaches. Such women have financial problems in buying goods from the wholesale market, problems in finding a place at the pola to sell their products, or problems in transporting their goods to other polas. The disadvantaged condition of the women traders compounds their vulnerability thus rendering them victims to sexual exploitation. Another important problem women traders face in the pola was related to their power to bargain. One woman explained it this way:

I buy vegetables from the Thambuttegama wholesale market in the morning. I buy them using a loan and repay the money to the traders in the evening when the pola is over. I do not earn much profit. Some days I have gone home with 20 Rs, after shouting the whole day. I also have to pay the rent to the tax collector. We cannot bargain like men. I am not educated. I think you have to have university degree to trade at this pola. Consumers are cheating us. They look for cheaply priced vegetables and they come to women traders as they can be cheated easily. Consumers who come in the early hours of the pola select the good vegetables and those who come in the evening are left with damaged vegetables. Then we have to sell them at lower prices, yet we still have to pay back the wholesale trader the full price for the good vegetables. When we buy vegetables at the wholesale market we cannot choose the good ones, but when consumers buy, they choose the good ones and they ask us to reduce the price of the damaged ones. Men at the pola do not allow the consumers to select vegetables, but we cannot do this.[47]

Due to lack of bargaining (and, possibly, physical) power, many women at pola earned less profit than men. They also constantly came under threat from male traders at the pola for selling goods at lower prices. Sometimes the women went home without any profit after paying the tax for occupying the market space for the day. Although men were often able to negotiate with the tax collectors, many women did not have the necessary physical or psychological strength to negotiate in this way. Furthermore, while tax collectors were happy to enter into negotiations with male traders, they were less likely to cede any advantage to women whom they perceived to be below them in social status.

Male pola traders operated in many polas in System H. However, unlike the male traders, women traders were not in a position to travel longer distances and were forced to operate in one pola only. One of my respondents, a grandmother, explained her restriction on travel as follows:

I have seven children and five of them are married. Two of my daughters are working in the Middle East as housemaids. I am taking care of their children along with my youngest daughter who is still at home. Therefore I cannot go to other pola rawume in the area. I come only to the Wednesday circuit here. Earlier I used to go to Nochiyagama pola. Now, I cannot do so as I have to take care of my grandchildren.[48]

Women may have disproportionately faced mobility constraints that limited their ability to travel or sell at markets located some distance from their households and communities. Trading at markets requires mobility and social interaction. The majority of the male traders attended several different pola throughout the week. Debra Winslow Jackson,[49] in her study on 'Polas in central Sri Lanka,' notes that traders reap many advantages by attending several pola. They established good links with different customers and became familiar with places to stay overnight or to store goods. In addition, many male traders operated in groups, which maximised their profits and ensured full employment as they moved around the various pola in the area.[50] However, women traders could not work in this way due to home and community commitments. Women's mobility was also constrained by societal attitudes, age and physical capability:

Earlier I used to visit three pola, now I come to this pola only. I am old and I am sick. I do not even come regularly to the Thambuttegama pola.[51]

Mahaweli women's restricted mobility due to unpaid family farm work and household duties has been highlighted generally by a number of other researchers.[52] Lack of mobility makes women dependent upon just one or a few pola to sell their products. In common with Respondent 13 and unlike their male counterparts, many women at Thambuttegama pola have limited mobility. The majority of women traders preferred to operate at a particular pola. Proximity to their own village was a key factor in their choices.

Already women traders are neglected by the society. If we travel to more polas and if we stay overnight in a place for trading purposes, people will speak badly of us in the villages.[53]

In schools our children are looked down upon, even by teachers, if it is known that their mother is a pola trader.[54]

The foregoing statements outline the difficult conditions under which the women pola traders work. My research demonstrates how they were caught between societal expectations and survival. As in most traditional communities, the lives of pola women are governed by a set of socio-cultural values and norms. Hence, factors such as religious beliefs and rationalisation, cultural norms, behavioural norms, myths, perceptions, and moral values exert a strong influence on the pola women's socio-economic and cultural lives. Nevertheless, pola provide a viable means of livelihood for many impoverished women. Pola trade has given many women strength and confidence, even after becoming single parents with extra family responsibilities. Trading in pola did not require a large amount of capital and entry was relatively easy compared to other formal sector employment.

Conclusions

At the time of my research in the Mahaweli settlements, growing insecurity and poverty created conditions whereby women were breaking barriers and entering the public sphere to ensure their survival. Due to their exclusion from the economic benefits of the AMDP and their subordination within domestic and community contexts, women were forced to seek employment outside the home often in marginal sectors of the economy. Poverty, unemployment, or marital status difficulties made it imperative for women in Mahaweli to have their own source of income. The need to find paid work almost always added an extra burden to these already marginalised women.

The foregoing discussion has provided some insight into the magnitude and nature of the vulnerabilities experienced by women pola traders. Using data gathered from in-depth interviews and informal discussion, I have highlighted the different forms of vulnerability experienced by the women traders at Thambuttegama pola. These include fear of eviction, the double burden of combining paid work with domestic roles and responsibilities, negative socio-cultural attitudes towards pola women, limited mobility, less bargaining power than men enjoy and the risk of sexual harassment. Furthermore, pola women were concerned about their vulnerabilities both in the immediate context of the market environment and at the wider community level.

The sacrifices undertaken by pola women to improve their families' living conditions cannot be measured in monetary terms. The pathway out of poverty chosen by these women is not an easy one: it involves struggle, shame, fear, and hard work. Pola women are recognised as being economically important, yet they have been socially marginalised in the Mahaweli economy. For most of the women interviewed, trading at polas is simply a survival strategy.

The narratives discussed in this article show that participating in pola trading has increased the vulnerability of women pola traders with many losing self-esteem and a sense of dignity as a result of the nature of the work in which they are engaged. However, in terms of personal empowerment, they at least have the ability to respond to poverty and to challenge the norms of a male-dominated arena. They know how to interact with the outside world, and they have self-confidence. Nevertheless, since they do not have the ability to control the prevailing patriarchal ideologies in society, economic participation by pola women does not necessarily lead to any changes in their power status in terms of the relational dimension of empowerment. While the women often developed loose networks of cooperation between themselves, this kind of cooperation is very weak as they cannot compete with the male traders, nor can they negotiate as a group with government officers or local politicians who play important roles in the administration and allocation of stalls at polas.

Economic participation has empowered pola women to a certain extent at the individual level. However, I have demonstrated in this paper that economic participation has not helped the women achieve collective or close relationship empowerment as defined by Rowlands. I am, in fact, sceptical as to whether individual level empowerment alone can strengthen or lead to collective and close relationship empowerment, as the women face multiple forms of vulnerability at home, at the market place and in society.

In the future, women's economic improvement and empowerment programmes in Sri Lanka will need to give special attention to pola women. These women have a right to a life with dignity and steps must be taken to alleviate the various vulnerabilities they face. Attention should especially be paid to their safety at the pola. The important contribution the pola women make to the betterment of their own families and the overall economy must be recognised. Patriarchal attitudes should acknowledge the fact that the women are involved in both productive and reproductive roles. Future initiatives to empower women must take into consideration not only women's participation in economic activities but also the need to reduce their vulnerabilities. It is only through reducing vulnerabilities that women can be empowered in the long run.

Endnotes

[1] Respondent 2. Thambuttegama pola, 7 March 2007.

[2] Kamalini Wijethilake, Unraveling Histories: A Three Generational Study, Colombo: Centre for Women's Research (CENWOR), 2001, p. 59.

[3] Swarna Jayaweera, 'Women in education and employment,' in Women in Post Independence Sri Lanka, ed. Swarna Jayaweera, Colombo: Vijitha Yapa Publications, 2002, pp. 99–142.

[4] When selecting households for settlements, first priority was given to the first two categories. Government party members of parliament made the final selection of the third category. They gave priority to their party supporters.

[5] A 'central place' is a location where centralised functions are performed which offers a service or product to its surrounding market regions. See Ray M. Northam, Urban Geography, New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1979, p. 156.

[6] M.D. Nelson, Mahaweli Programme and Peasant Settlement Development in the Dry Zone of Sri Lanka, Peradeniya: University of Peradeniya, 2002, p. 116.

[7] Nelson, Mahaweli Programme and Peasant Settlement Development in the Dry Zone of Sri Lanka, p. 140.

[8] George Owusu and Ragnhild Lund, 'Markets and women's trade: exploring their role in district development in Ghana,' in Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift—Norwegian Journal of Geography, vol. 58, no. 3 (2004):113–124, p. 117.

[9] L.P. Rupasena, 'Preliminary analysis of rural periodic markers (polas) in the central and north central provinces of Sri Lanka,' in Rural Urban Interface in Sri Lanka, ed. M.M. Karunanayake, Nugegoda: Department of Geography, University of Sri Jayawardanepura, 2003, pp. 44–61.

[10] Rupasena, 'Preliminary analysis,' p. 44.

[11] For a permanent stall, the tender's levy was 250300 Sri Lankan Rupees ($US1 = 110 Rs; $AU1 = 100 Rs per day). For open ground, the rent varied from 150 Rs to 200 Rs, depending on the size of the ground each pola trader occupied.

[12] These views are derived from the informal discussions conducted with government officers, senior citizens and other women in System H.

[13] Christiana Solomon, 'The role of women in economic transformation: market women in Sierra Leone,' in Conflict, Security and Development vol. 6, no. 3 (2006):411–23, p. 416.

[14] Robert Chambers, 'Editorial introduction: vulnerability, coping, and policy,' in IDS Bulletin, vol. 20, no. 2 (1990):1– 7, p. 2.

[15] Robert Chambers, 'Poverty and livelihoods: whose reality counts?' in Environment and Urbanization, vol. 7, no. 1 (1995):173–204, p. 189.

[16] Anju Malhothra and Mark Mather, 'Do schooling and work empower women in developing countries? Gender and domestic decisions in Sri Lanka,' in Sociological Forum vol. 12, no. 4 (1997):599–630, p. 602.

[17] World Bank, Engendering Development: Through Gender Equality in Rights, Resources and Voices, New York: World Bank and Oxford University Press, 2001, p. 109.

[18] Caroline Moser, Gender Planning and Development: Theory Practice and Training, London: Routledge, 1993.

[19] Wijethilake, Unraveling Histories, p. 27.

[20] World Bank, Engendering Development: Through Gender Equality in Rights, Resources and Voice, p. 109.

[21] Robert Chambers, Challenging the Professions: Frontiers for Rural Development, London: Intermediate Technology Publications, 1993; Caroline Moser, 'Gender planning in the Third World: meeting practical and strategic gender needs,' in World Development, vol. 17, no. 11 (1989):1799–825, p. 1815; Naila Kabeer, 'Women's wages and intra-household power relations in urban Bangladesh,' in Development and Change, vol. 28, no. 2 (1997):261–302, p. 265; Naila Kabeer, 'Resources, agency and achievements: reflections on the measurement of women's empowerment,' in Development and Change, vol. 30, no. 3 (1999):435–64, p. 437; Jo Rowlands, Questioning Empowerment: Working with Women in Honduras, Oxford: Oxfam Publishing, 1997, pp. 13–14, 110–41; Srilatha Batliwala , 'The meanings of women's empowerment: new concepts from action,' in Population Policies Reconsidered: Health, Empowerment and Rights, ed. Gita Sen, Adrienne Germain and Lincoln Chen, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1994, pp. 127–38; Jane L. Parpart, Shirin M. Rai, and Kathleen Staudt, 'Rethinking em(power)ment, gender and development: an introduction,' in Rethinking Empowerment: Gender and Development in a Global/Local World, ed. Jane L. Parpart, Shirin M. Rai, and Kathleen Staudt, London, New York: Routledge, 2002, pp. 3–16.

[22] Kwok-Fu Wong, 'Empowerment as a panacea for poverty—old vine in new bottles? Reflections on the World Bank's conception of power,' in Progress in Development Studies, vol. 3, no. 4 (2003):307–22, p. 310; Jo Rowlands, Questioning empowerment, working with women in Honduras, p. 13.

[23] Rowlands, Questioning empowerment, working with women in Honduras, p. 111.

[24] Rowlands, Questioning empowerment, working with women in Honduras, p. 119.

[25] Rowlands, Questioning empowerment, working with women in Honduras, p. 115.

[26] Rowlands, 'Using the model: empowerment, gender and development,' p. 129.

[27] The field survey was conducted as part of my doctoral research.

[28] M.M. Karunanayake, Y.A.D.S Wanasinghe and R.M.K. Ratnayake, 'Dynamics of rural periodic market circuit in the Anuradhapura District of North Central Sri Lanka,' in Rural Urban Interface in Sri Lanka, ed. Karunanayake, Nugegoda: Department of Geography, University of Sri Jayawardanepura, 2003:62–103. Rupasena, 'Preliminary analysis,' p. 44.

[29] Sinhala, Hindu New Year, which falls on 14 April each year, is a very hectic period in terms of business in many towns as well as rural areas. Most people spend a large part of their savings on buying clothes for their families, preparing sweets and renovating their homes.

[30] Karunanayake et al., 'Dynamics of rural periodic market circuit.'

[31] Jayaweera, 'Women in education,' p. 120.

[32] Jayaweera, 'Women in education,' p. 120.

[33] Mahaweli (AMDP) is one of the re-settlement schemes in the country and there are several other re-settlement schemes already existing. In all such resettlement schemes, including Mahaweli, women's legal inheritance of land is denied. Most married women have indirect access to land through their husbands. However, in the case of divorce, separation or abandonment, even this right is lost. This has been a serious impediment to achieving a better standard of living for women. Regulations regarding land inheritance for women who live outside the settlement areas (rest of the country) are not the same. In the rest of the country, most women enjoy a legal inheritance right from their parents regardless of their gender.

[34] Respondent 10, Thambuttegama pola, 21 March 2007

[35] Female traders buy vegetables from wholesale vegetable markets for resale at polas.

[36] Respondent 8, Thambuttegam pola, 14 March 2007.

[37] Respondent 14, Thambuttegama pola, 2 May 2007.

[38] Respondent 6, Thambuttegama pola, 14 March 2007.

[39] Respondent 7, Thambuttegama pola, 14 March 2007.

[40] Respondent 1, Thambuttegama pola, 7 March 2007.

[41] Respondent 11, Thambuttegama pola, 28 April 2007.

[42] Anoja Wickramasinghe, 'Women's role in rural Sri Lanka,' in Different Places Different Voices: Gender and Development in Africa, Asia and Latin America, ed. Janet Henshall Momsen and Vivian Kinnaird, London and New York: Routledge, 1993, pp. 159–75.

[43] Respondent 12, Thambuttegama pola, 2 May 2007.

[44] Wijethilake Unraveling Histories, p. 30; Vinitha Jayasinghe, A New Vision: A Feminist Perspective in Sri Lanka, Rajagiriya: Pace Printers, pp. 74–75.

[45] Respondent 4, Thambuttegama pola, 14 March 2007.

[46] Jayasinghe, A New Vision, p. 111.

[47] Respondent 9, Thambuttegama pola, 4 April 2007.

[48] Respondent 13, Thambuttegama pola, 2 May 2007.

[49] Debora Winslow Jackson, 'Polas in central Sri Lanka: some preliminary remarks on the development and functioning of periodic markets,' in Agriculture in the Peasant Sector of Sri Lanka, ed. S.W.R.De.A. Samarasinghe, Colombo: Wesley Press, 1977, pp. 56–84.

[50] Nelson, 'Mahaweli Programme and Peasant Settlement Development in the Dry Zone of Sri Lanka,' p. 147.

[51] Respondent 3, Thambuttegama pola, 7 April 2007.

[52] Ragnhild Lund, 'Gender and place: examples from two case studies,' thesis submitted for the doctor rerum politicarum examination, Department of Geography, University of Trondheim, 1993, p. 9; Nedra Weerakoon Goonewardene, 'Policies and programmes of the Mahaweli Settlement Scheme and its impacts of the role and status of women,' in Women in Development in South Asia, ed. V. Kanesalingam, New Delhi: Macmillan India Limited, 1989, pp. 237–58, p. 248.

[53] Respondent 12, Thambuttegama pola, 2 May 2007.

[54] Respondent 5, Thambuttegama pola, 28 March 2007.

|

Figure 1. Female traders in Thambuttegame Pola. Photograph taken by author, 4 April 2007.

Figure 1. Female traders in Thambuttegame Pola. Photograph taken by author, 4 April 2007.

Map 2. Pola visited by female traders in Thambuttegama. Map prepared by Swarna Seneviratne, cartographer, Department of Geography, University of Peradeniya, Sri Lanka.

Map 2. Pola visited by female traders in Thambuttegama. Map prepared by Swarna Seneviratne, cartographer, Department of Geography, University of Peradeniya, Sri Lanka.