Dancing on the Weekend

Papua New Guinea Culture Schools in Urban Australia

Jacquelyn A. Lewis-Harris

-

Pacific expatriate communities throughout the urban centers of New Zealand, Australia and the United States foster groups of Pacific island artists that are committed to preserving and advancing various forms of customary art from their indigenous cultures. The rationale behind this activity varies with the community and country, but the intent—perpetuation of cultural practices and identity—is comparable among many Pacific diasporic communities.[1] The choreography and performance of old and new dance forms is one of the most public and popular communal interaction in the creation of these artistic endeavours is often more important and valuable, in certain aspects, than the final product. Due to these practices of choreography, costume design, headdress and textile construction and decoration, chants and customary singing, oral history retention, young people begin to better understand and respect their indigenous cultural traditions while gaining a healthy dose of self-esteem in embracing another facet of their ancestry. The process engages younger generations in partnerships with older members of the community and visiting relatives, providing invaluable cultural education for the younger members. In the Australian-Papua New Guinea communities, as opposed to their indigenous Papua New Guinean environment, women appear to be the key to many of the cultural preservation and dance education movements, acting as teachers, cultural arbiters, and performers.

-

This paper will examine the shifting of cultural knowledge from males in Papua New Guinea (PNG) to females in Australia, because of migration patterns, external social pressures and the death of knowledge keepers. It will provide a brief history of Papua New Guinean migration to Australia and the consequential formation of P.N.G. cultural groups, schools and dance troupes in the major urban areas. As the Motu Koita and Solien Besena women in Australia are very active in dance group formation, an abbreviated history of Motu Koita and Solien Besena cultural interaction will be presented as well as a description of their subsequent activities in Brisbane and Sydney. I will employ instances from the experiences of two Soilen Besena/Motu Koita female artists—Wendi Choulai and Theresa Barlow—to illustrate the unique role of women as cultural leaders and discuss their efforts to address the conundrums posed in preserving and promoting customary dance and certain art forms. Finally, youth involvement, the future continuation of the dance troupes, and the ripple effect of Choulai's groundbreaking performance piece at the 1996, Second Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art in Brisbane, Australia will be examined.

From Papua New Guinea to Australia – social clubs and weekend cultural schools

- Soilen Besena and Motu Koita women were part of the gradual post-colonial migration from P.N.G. to urban Australia between 1974 and 1976. Primarily married to English and Australian males who held positions as civic servants and government officials, the women quietly settled into middle-class neighbourhoods around Sydney, Brisbane and Melbourne. Several waves of women and their families came in the late 1980s and early 90s due to economic and social uncertainities in PNG By 2001, the first waves of Papuan immigrants, their children and miscellaneous spouses had increased the Papua New Guinean population to more than 23,600,[2] with 75 per cent of the population living in the states of New South Wales and Queensland. These migrants raised their children, acquired jobs, formed social groups and basically lived as close an Australian life-style, as possible.

-

As community populations grew, Papua New Guineans formed community-based social groups which became the nexus of cultural activity and social congregational points. By the year 2002, each Australian state or territory, with the exception of Western Australia, had at least one P.N.G. association in the largest town or city. The number of associations in each city was dependent upon the overall population size and the number of early Papuan migrants who had settled there. Sydney, for example, had two official associations: the P.N.G. - Australia Association, which was predominately comprised of Motu-Koita families who migrated before 1975 and the P.N.G. Wantoks' Association, which was comprised of a mix of older and recent Papua New Guinean migrants and temporary residents. In addition to providing social and cultural support to the adults, the P.N.G. associations' activities and weekend cultural schools supplied a positive atmosphere and education for the children. Association members were very concerned over the loss of cultural practices and knowledge as well as their children's lack of exposure to their indigenous culture. The majority of the organisers and instructors were women, thus providing a female-biased view of cultural history, men were not excluded but the demographics favoured women. The associations usually incorporated more than one cultural group's history and discussed PNG culture as a whole. Ranu Ingram James, one of the founding members of Drum Drum, a professional Papua New Guinean-Australian performance group, discussed her experience with the PNG culture schools held in Darwin:

We went to school during the week and we went to Papua New Guinea School on the weekends. And we learned about Papua New Guinea and did dancing and singing and cooking and all sorts of stuff about being Papua New Guinean. And we did that every day but it was a formal Papua New Guinean education thing that they did on a Saturday.[3]

-

The association schools' influence ebbed and flowed, as they were dependent upon groups of volunteer teachers who were willing to develop and maintain the classes. In 2007, Brisbane, Melbourne and Sydney groups were in the process of reviving their schools, but they were having difficulties, as the majority of the work fell upon the shoulders of a few women. These women were typically involved in many other community projects, including the semi-professional dance groups. It was interesting to note that while the status of the associations' schools were fluid and unstable, the dance groups derived from the cultural schools appear to have maintained a stable presence in the Australian cultural scene.

Cultural history of Solien Besena and Motu Koita interaction

-

In order to grasp a better understanding of the significance of Australian-based Solien Besena and Motu Koita women in the role of dance group leaders, it is important to discuss the interrelation of gender, dance and economics among the Motu Koita and Solien Besena people in PNG The Motu Koita people were a conglomerate of two dominate indigenous groups, that resided in the capital city Port Moresby, adjacent islands and lands along the central south coast of PNG They were one of the first groups to interact with the British and Australians and fall under colonial rule. The Koita have inhabited the Sogeri Plateau and immediate inland areas for some 3,000 years. They periodically dominated a large portion of the inland regions between Galley Reach and Port Moresby. The Koita developed a long-standing interrelationship with the Motu, sharing marriage partners, trade routes and costal village sites.[4] The Motu were late arrivals to this area, with their archaeological record dating between AD 1200 and 1700.[5] Arriving in three waves, near the present site of Port Moresby and adjacent coastal sites, they brought new technology, superior sea craft, ceramics and an extensive trade system.[6]

-

The Solien Besena are indigenous to Tatana Island, and comprise a dominant sub-group of the Motu Koita. During the 1800s, South Coast Papuans, Malaysian, Indonesian and European seamen were engaged in a lively trade of sandalwood, cedar, bird of paradise skins, turtle shell, bêche-de-mer, and pearl shell.[7] Among this group were Javanese plumage and bêche-de-mer traders from Surabaya, East Java in Indonesia, known around the Port Moresby area as 'Malays'.[8] The Solien Besena clan was founded in the late 1800s through the intermarriage of Solien, a Javanese beche-de-mer trader to Daihanai and Biria, two daughters of the Nenehi Motu chief of Tatana Island. Although the present ancestors do not know the exact date of this marriage, they acknowledge that it was before the Australian acquisition of coastal land adjacent to Tatana Island, in 1886.[9] Researchers acknowledge that Solien and other foreign men had gained a certain amount of influence in the community through their marriage into the local groups:

In 1886 the Australian government purchased 552 acres near the harbor to secure frontages by the shore before the Papuans occupied them on the advice of certain Malay and South Sea Islanders who had taken Motu women as wives and who use some influence over the aboriginal villagers.[10]

-

Solien's wives and relatives provided access to both local and regional lands in Port Moresby and the Galley Reach area to the west. In a positive and shrewd political gesture, Solien adopted his wives' culture and that of the neighbouring Roro, thus merging with the local Motu Koita people. Cultural transmission was primarily governed through trade alliances between the Roro, Nara and the dominant Motu Koita. Choreography, songs, apparel and costume materials were part of that exchange, which formed a loose cultural network that promoted certain stylistic commonalties, while retaining the idiosyncrasies that defined the individual cultures. The twenty-two original offspring and resultant children, in turn married people from the Doura, Motu-Koita and Nara groups with some of the women being married off to Motu Koita trading partners in the Rigo area.[11] The present day Solien Besena culture is a mixture of Motu-Koita, Roro, Doura and Surabaya, Javanese cultures. The female artists interviewed for this study are direct descendants of this Solien Besena group.

-

In PNG, Solien Besena males interacted and traded with all of these groups to obtain a variety of dance ensembles, choreography and music. Their dance tradition was dependent upon exchange and reciprocity between their trade and marriage partners. In regards to south coast dance and music ownership, Seligmann noted:

Both songs, dances are strictly copyrighted, and in the old days the unauthorized use of a song or dance might have led to war. The only legitimate manner for people to obtain the right to dance or song not their own was to buy it, as the folk of Hohodai village bought the rights to use the song maginogo.[12]

-

Ceremonial songs were usually sung in a series and were sold or traded together with the accompanying dance cycles.[13] This material and other cultural traditions were primarily transferred through the male line. Female's dance skirts, for example, were a part of this cultural trade:

For several generations, the Solien Besena of Central Province have obtained their dance skirts by trading shell lime, a major component in betel nut use. The coastal villages located between Brown River and Mekeo areas provide the majority of their shirts. As a consequence of this successful trading system, the Solien Besena women have no history of skirt production.[14]

-

All of the Solien Besena dances and a great portion of their dance costumes were obtained through their male trading partners. For example, the Gumo Roho funeral dance, which Wendi Choulai organised and performed in the 1996 Brisbane Triennial of Contemporary Art, was originally bought from the Roro through the Nenehi Motu, the founding mother's clan.[15]

-

Dance was one of the primary artistic traditions adapted by the Motu Koita and Solien Besena. Along the PNG south coast, this activity was a major part of all feasts, ceremonies and special occasions, such as a boy's initiation, the presentation of newly tattooed girls, agricultural fertility and mortuary ceremonies.[16] Seligmann noted that specific dances and songs were grouped together into classes named Ita, Turia, and Koriko.[17] Some of these dance cycles, as the Ita, in Koita and Roro funerary ceremonies, lasted for two to three days with groups of songs that complemented each dance round. In the distant past the Solien Besena had purchased the Ita dance complex and portions of it were later carried to Australia in the form of the Roroipe and Guma Roho. This method of cultural transmission between male trading partners placed extraordinary value upon dance and artistic production and in turn, escalated the preciousness of the various components. The monetary significance of dance components was transferred along generations, and in Australia the dance traditions and related objects became even more precious and controlled by senior women in the absence of male elders. The custodianship of the dance and its components was one of the major underlying factors in identity and ownership disputes, family relationships and female power among the Australian-based Solien Besena and Motu Koita groups.

Women as cultural instructors

-

My interviews and research have revealed that Soilen Besena and Motu Koita women in Australia create the majority of the dance groups through clan, community and church affiliations. There are rare exceptions where there are male organisers, as in the Adamson-Bray family dance group in Brisbane, but as a whole, women dominate the leadership roles. The group leaders are closely tied to their extended family and there are obligations that come with this relationship. These commitments include the teaching of the narrative history and the ancestral interrelationships to other groups in Australia and PNG, as well as esoteric cultural knowledge related to dance and other arts. The esoteric knowledge is limited and guided through a series of exchanges and careful negotiations. Initially, the women cultural experts had to play the male dance role, when teaching dance and cultural history, as there were so few men in Australia. Their first inclination was to modify the dances but they felt obliged to teach and perform the dances correctly. Eventually they incorporated video recordings of male roles and flew elders in from PNG for important ceremonies.[18] Unfortunately, by 2009 many of the Soilen Besena elders in PNG had passed on and many of the young men have moved to urban areas and are not learning the esoteric knowledge associated with the dance ceremonies. Consequently PNG and Australian-based Soilen Besena women are now negotiating with the male elders to possess some, if not all of the knowledge.[19] As the balance of male and female dancers as well as the accompanying knowledge of the choreography is crucial to the proper performance, this lack of participating males has caused a crisis. Young Australian-based Soilen Besena and Motu Koita boys and men are continually being recruited but dancing has to compete with the more popular activities such as rugby and football. Even though there is a cultural and family commitment to participate, the outside influences of 'their mates' opinions often hold sway over their commitment to participate. Two of the young male teens that I interviewed, frankly told me that they continued to dance because their parents required them to dance in their mother's group. They were sometimes embarrassed when their 'mates' saw them perform at festivals, because their bark cloth breech cloths exposed too much skin.[20] Although the women leaders are having a difficult time keeping the gender balance within their troupes, they continue to teach and encourage the next generation to participate in the dance.

Women as cultural agents

-

In this paper a closer examination of Theresa Barlow and Wendy Choulai's work in Australia will better illustrate the pertinent agency of women artists in the continuation of dance traditions. I will also discuss the commitment and sacrifice of women in promoting and performing dance in Australia.

- Theresa Barlow

-

Theresa Barlow is the Biria Solien Besena and Doura leader of Hiri Besena dance group. She is related to the Soliens through the maternal line and is a first cousin of Wendi and Ruth Choulai. Barlow lives with her Australian husband, daughter and two sons in the northern suburbs of Brisbane. She is well educated, having graduated from the University of Papua New

Guinea, in journalism. Before her marriage in 1976, she worked as a teacher and a writer for the Post Courier, the major newspaper in Papua New Guinea. The Barlows moved from PNG to Melbourne in 1979; they were later transferred to Brisbane, Queensland in 1980, where she was reunited with her extended Solien Besena family.

-

Barlow was very active in the Melbourne-based Folkfest organisation and volunteered her time with the Brisbane Ethnic Music and Arts Centre, a large, city art organisation. She was one of the first Papua New Guineans to be appointed to the Brisbane multicultural festival board. Barlow was also deeply involved in the PNG organisations. In 1983 and 1984, she helped organise the first community dance celebrations to mark PNG independence. Barlow formed four dance groups between 1984 and 2000. The first group performed a mix of Polynesian and PNG dances and primarily consisted of her family members. In 1985 her Australian cohorts suggested that she start a Papua New Guinean dance group, as there were more Papua New Guineans migrating into Brisbane and there was no professional group established at that time. This was the beginning of Moale, a troupe consisting of her immediate family, her cousin Alma Adamson, children of PNG-Australian marriages, immigrant women and their children. Organised in 1986, they performed a selection of Motu Koita dances with a strong emphasis on Solien Besena choreography. Moale was fairly successful in introducing Australian audiences to PNG culture, obtaining local and national grants, and representing the country in several regional festivals. Adamson and Barlow later separated and Barlow established the Besena dance group. Once again, by employing her connections with the regional and community organisations, she was able to develop a large, successful semi-professional troupe. Besena was the only PNG group to serve as the opening act for the 1993 Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Arts held in Brisbane. As the group grew, and the non-Solien Besena members outnumbered the Soilen Besena and their relations; Besena split into two. One group became solely Motu Koita while Barlow formed a new Solien Besena-Doura group called Hiri Besena. It was advertised as:

a group of family members both PNG and Australian born, who have joined forces to promote their cultural heritage by way of traditional songs and dances. The family ambition is for the younger generations not to lose sight of their heritage which is rich in history and culture. The maintenance of this ambition can only be achieved by the active participation of both the older and the younger generations combining with a unified spirit.[21]

-

As of 2005 the group consisted of thirty occasional dancers; the number varies with school activities, as twenty of the dancers are under sixteen with five under the age of ten. They work hard at keeping their performance true to the older styles, maintaining the correct words, choreography and costumes. Hiri Besena also serves as a cultural school. Barlow teaches art through costume construction, language and clan history through the songs and choreography. She videotapes their performances as well as other groups to help them improve their art through reflection and observation. These activities are instrumental to the younger dancers' cultural education. My interviews confirmed that the younger members believe they have learned responsibility, respect for their elders, and a better understanding of their PNG heritage through their participation.

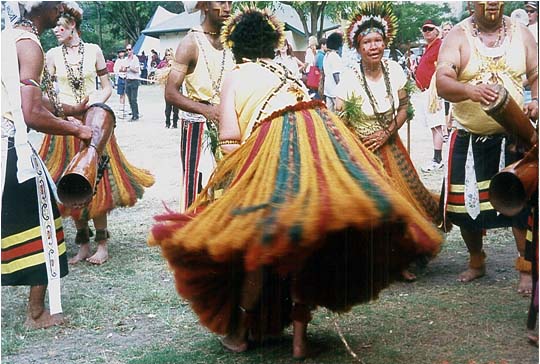

Figure 1. Theresa Barlow's group 'Hiri Besena', Brisbane at the PNG Independence Day Celebrations,

September 2000. Photographer, Jacqueline Lewis-Harris.

-

An obstruction to group sustainability is the dwindling source of private, state and local government funding for the arts. With eight PNG groups and numerous Pacific groups now in the Brisbane area, the competition can be very staunch. The Solien Besena/Motu Koita groups are not financially well off; they have to constantly raise funds to keep the groups afloat. Female leaders hold full time jobs, outside their leadership roles and rely upon their personal money and fundraisers to support the groups. The upkeep and maintenance of the troupes' dance costumes is the equivalent of maintaining a small valuable art collection. Each female dancer's costume includes three imported, Papua New Guinean skirts, worth a total of $AU210 (2005 estimate). The tapa bark cloth for tops and streamer decorations is bought from the Samoan community and can range up to $AU50, a piece. The total female costume can run as high as $AU535. The high cost of costume construction and maintenance places a strain on the finances of any troupe. Although the group leaders try to adhere to their interpretation of the traditional, they often have to modify their designs due to the cost and lack of raw materials. Unlike their PNG-based relatives they have little access to dog teeth, mull berry tapa cloth, cockatoo and bird of paradise feathers. Jewellery is often passed along family lines, but other costume items are replaced with broadcloth and chicken feathers.

- Wendi Choulai

-

Wendi Choulai was born in the gold-rich town of Wau, Papua New Guinea in 1954. Shortly after her birth, the family moved to the capital city of Port Moresby. Although Port Moresby was her primary residence, she spent prolonged stays with their mother's clan, the Daihanai Solien Besena, observing and participating in dances and ceremonies. Choulai's upbringing was shaped by a combination of Malay Chinese, Solien Besena, Motu-Koita and Australian cultural influences but her artistic roots were firmly established in the Solien Besena culture.

Figure 2. Photo of Wendi Choulai, in her studio in Port Moresby, painting on fabric with

Jacqueline Lewis-Harris, 1983. Photographer, Wright E. Harris III.

-

Unlike her cousins, she was a full-time practising artist who pursued a degree in the fine arts. After matriculating from educational institutions in Papua New Guinea and Australia, Choulai attended the Papua New Guinea National Arts School, where in 1986, she held the distinction of being the first female graduate of the textile arts program. While still in the National Arts School, Choulai and her sister Ruth opened PNG Textiles, a workshop and studio. Its formation provided employment for artists, contributed a new market outlet, and encouraged other artists to open their own small businesses. The studio's success marked a vigorous and competitive time for Papua New Guinean contemporary arts. The Choulai sisters became role models for young Papua New Guinean women attempting to become artists in spite of family and societal opposition. From 1984 to 1993, Choulai represented Papua New Guinea in several overseas art venues including the Commonwealth Arts Festival in Edinburgh Scotland, the Pacific Arts Association in Adelaide Australia, exhibiting in Sydney and London as well as the World Crafts Council Meeting in Jakarta, Indonesia. When Choulai moved to Melbourne, in 1994, her artistic activities became a catalyst for new and expansive Solien Besena art forms.

-

In 1995, Choulai was invited to create a work for the Second Asia Pacific Triennial and also at that time she was completing her Masters degree from the Royal Institute of Technology in Melbourne. Choulai noted:

I accepted an invitation to the exhibit at the 1996 Asia Pacific Triennial at the Queensland Art Gallery as a means of bringing together the central purpose of my thesis of integrating contemporary design within ritual and proving that it is not necessary to break with tradition to be a contemporary Oceanic designer in the modern market. It also demonstrates how designers from the Pacific can articulate their culture in a meaningful way with legitimate designs that can be placed in the 'western' market without losing their cultural value.[22]

-

She decided to organise a Guma Roho, a customary dance that would honour the spirit of her grandmother, Agnes Daihanai Solien. This customary dance is part of a larger ceremonial cycle called the Roroipe and was performed in the Solien Besena, Roro and Motu Koita cultures. British anthropologist, C.G. Seligman was one of the first researchers to describe the Guma Roho:

When dancing in columns, the movement is usually slow and dignified, but when one or two girls danced by themselves behind, or at the side of the columns, it is customary for them to dance so violently, that the component strips of the petticoat tied over the right hip, fly up in a spray of fibers, allowing the tattoo on the buttock and thighs to be seen.[23]

-

Although the skirt swing has been modified for conservative contemporary audiences, the choreography described by Charles Seligmann, mirrors the contemporary Australian-Papua New Guinean performances. The choreography was designed to present the audience with a vision of clan unity. Through their grouping, the dance portrayed an impressive unified block of dancers, displaying the collective supremacy and strength of the clan. The Guma Roho ceremony consists of a series of line dances in which the men lead the performance and the younger women dance in the last line. The best dressed and most important male dancers and drummers lead the dance, setting the pace with their characteristic slow rhythm, played to mimic the human heartbeat. The lines separate to the left and right, forming a broad aisle in the middle. Pairs of dancers then demonstrate their best form as they dance down the middle of the aisle, expressing their individuality in small but subtle ways. The men represent the collective power and wealth of the clan through their attire and dance posture, as they wear elaborate, animated, three to four foot high headdresses called tubukas. The women embody the horizontal and the grounded element of the dance. When dancing in the line, women keep their feet still but sway their skirts and bend their bodies just above the hips. Their arms and hands are fairly stationary, with the hands resting upon each other right over the navel area. The emphasis is placed upon the swing of the hips and the bend of the knee. This movement was described as imitating the movements of the 'Willy Wagtail' or the White-Breasted Thicket Fantail Rhipidura leucothoraxa.[24]

Figure 3. The more extreme version of the Willy-Wagtail skirt swing by Alma Adamson,

Brisbane PNG Independence Day Celebrations, September 2000.

Photographer, Jacqueline Lewis-Harris.

-

At the time of her grandmother's death in 1977, the imposition of Christianity stopped the performance of the Roroipe and Guma Roho among the Port Moresby Solien Besena. The move to Australia and a new generation had freed the restriction. Choulai's exhibit in the Queensland Art Galleries featured the series of Gumo Roho dances, her drawings and paintings, and a video recording of a Gumo Roho ceremony that was performed in PNG Choulai was the first Papua New Guinean female artist to exhibit hybrid contemporaneous forms in this venue. This multimedia presentation featured three dance groups, one of which came from Papua New Guinea. It was an artistic coup on several levels: as it helped her family to complete the funerary cycle, premiered the Gumo Roho and the Solien Besena culture in an international art exhibit, and provided a showcase for her 'modern' silk skirts series and other works of art.

-

The series of skirts featured several skirt designs. 'Wearable Grass Skirt 1' emulated the traditional

Figure 4. Drawing by Wendi Choulai of the 105 skirt prototype. Photographed by Jacqueline Lewis-Harris in Wendy Choulai's studio in 1986.

Figure 4. Drawing by Wendi Choulai of the 105 skirt prototype. Photographed by Jacqueline Lewis-Harris in Wendy Choulai's studio in 1986.

| |

sago fibre and designs from several types of skirts found in her ancestral village. This was the first ceremonial dance skirt to be constructed by a female Solien Besena woman and Choulai had to negotiated with her PNG elders to present this skirt in the ceremony. The head female dancer from the Australian-Solien Besena wore this skirt, while the young uninitiated female dancers wore special skirts called '105'. These skirts represented contemporaneous culture and were named after the '105' Goilala gang that lived in the hills behind the Choulai's Papua New Guinea compound. By naming the skirts '105' and incorporating a majority of plastic in their construction, Choulai acknowledged the impact of the urban milieu upon the continuation of Papua New Guinean dance ceremonies in both PNG and Australia.[25] She also designed and produced a series of two metre long 'lap laps' called 'Grass Skirt Design'. The daughters of Agnes Daihanai Solien-Choulai's mother and aunts wore these batik and hand-painted, silk lap laps during the dances. These pieces featured patterns that emulated the flash of colours produced by the sway of the customary dance skirts. The 'Grass Skirt Design' pieces were intended to represent the merger of the contemporary with the traditional; the Australian clan with the Papua New Guinean clan.

|

-

Choulai's artistic efforts in Papua New Guinea and Australia were an important catalyst for Soilen Besena cultural development in Australia. The performance and installation of the 1996 exhibit legitimised Solien Besena dance and ceremony in Australia and united the disparate Solien Besena groups from both the Daihanai and Biria clans. It also was the first Solien Besena funerary ceremony to be funded and promoted with money from the Australian government. The preparation activity introduced the younger Australian-born descendents to their PNG heritage and distant relatives. Alison and Lauren Chan, Wendi Choulai's nieces, discussed their gratitude in being able participate in the 1996 performance; they talked about their joy in learning more about their Solien Besena heritage, meeting their distant PNG relatives and being publicly recognised as being part of the Solien Besena clan. The experience also had a profound effect upon three of the teen dancers as they have continued to dance in Barlow's dance troop and now perform in festivals.

-

Choulai's groundbreaking performance and exhibit in the Second Asia-Pacific Triennial of

Contemporary Art also influenced Motu-Koita groups in Melbourne, Brisbane and Sydney.[26] The Gumo Roho performance sparked a flurry of activity among the Motu Koita and Solien Besena groups, who began seeking federal and state funds, while other groups endeavored to be included in more city- and state-sponsored programs such as Australia Day festivals and the Brisbane Folkfest. Choulai's effort to pay homage to her grandmother through the Guma Roho performance and exhibition inadvertently provoked a mini-cultural revival and interest in traditional dance among her relatives as well as the south coast Australian communities. Her untimely death in 2001 marked the end of a brilliant, groundbreaking career but her influence continues through the work of her sister, Ruth Choulai, her son, Aaron, and the members of her extended Solien Besena family.

Contemporary dance groups and gender in Australia

-

The majority of the Solien Besena and Motu Koita-related dance groups are found in the state of Queensland and most of my interviews were carried out in Brisbane with a few in Sydney and Melbourne. Members of the community and leaders of these groups have realised the importance of sustaining their cultural ties, as they fulfill a grounding element that Australian culture does not provide. In 2000 and 2003, I carried out a short survey based upon initial informal discussions with dancers and cultural keepers, to obtain a better understanding of the importance of the dance and cultural groups to young Australian-Papua New Guineans. My interviews with a sample of twenty-five dancers, 15 to 21 years of age, revealed that cultural pride, personal grounding, a sense of mental wellbeing and making a distinction between Australian and PNG culture, were their primary reasons for participating in these groups. While professing to enjoy the Australian lifestyle and culture, the young Solien Besena dancers talked about their joy in learning more about their paternal heritage, meeting their distant PNG relatives and being publicly recognised as being part of the clan. Theresa Barlow's daughter, Irene noted: 'This represents what we are. When others see us performing, they know we are from Papua New Guinea, from the South Coast.'[27] Participation also gave young dancers a unique status among their Australian peers and in their words, 'an option from just being Australian'. During a interview with two young sisters—whose mother was from the Papuan Gulf—they proceeded to describe their cultural day performance at their Canberra-based high school. The young women explained how their fellow classmates' Australian performances were 'bland and a mere shadow of American dances'. According to sisters, their Kerema dance performance 'had their fellow students intrigued, jealous and excited.'[28] They concluded that they had gained newfound respect from their peers and raised their status in their school, by dancing in their traditional dress of shell necklaces, sago leaf skirts and tapa cloth tops.

-

Typically, in my interviews, the young artists discussed how they were exposed to some type of experience that sparked their interest in PNG culture. It could have been participation in a traditional ceremony in PNG, a festival display of PNG culture in Australia or even a negative race-related incident. Anglo-Australian perceptions of gender, female stereotypes and supposed character attributions related to race, created negative external influences that shaped and influenced the lives of the young dancers. Patty O'Brien's significant historical study of colonial stereotypes of the exotic Pacific island woman and the encounters that contributed to these contrivances, notes that 'the dominant stereotype of Pacific women evolved through the sexualized economies of empire.'[29] She maintains that versions of the Pacific muse and island girl stereotypes continue in the present and I contend that the Motu-Koita and Solien Besena performances are framed by this type of colonial-based imagery. After all, P. N.G. was a former British and Australian colony in the not too distant past and in a few public dance performances that I attended this connection was actually mentioned. Racial perceptions intertwined with the stereotypes of Pacific and Papua New Guinean women intensify the opinionated atmosphere in which the youth operate. Scholars have documented the subjugation of Pacific island women and the objectification of their bodies whether through popular culture, commercialisation or other forms of exploitation.[30] Jane Desmond, in her book Staging Tourism, reflected:

From the beginning, this enabling discourse of the ideal native was "raced" and "gendered" in particular ways: female, not male, and "brown" not "black", "yellow", or "red". Combined with ideologies of colonialism, these ideas can produce imaginaries that merge the feminine and the exotic. As Marianna Torgovnick notes, what is "typical indeed of Western thinking about the primitive [is] the circularity between the concepts of 'female' and 'primitive'".[31]

-

Carefully-crafted travel literature from old Burns Philip commercial promotions, missionary tracks and art photography publications, attributed Papuan New Guinean women with a range of descriptors from seductive 'woodland nymphs' to savage 'primitive', depending upon the darkness of their skin and physical characteristics.[32] Catherine Lutz and Jane Collins[33] found that the widely distributed magazine, National Geographic, still promoted negative stereotypes of Papua New Guineans and Melanesians and the 'otherness' of these women, as late as the 1990s. Contrast these stereotypes with that of the more positive exotic Polynesian, to which the Solien Besena and Motu Koita groups were sometimes compared. The Polynesian phenotype was favored over the darker Melanesian, as 'the "Polynesian" figure is one of attractive exoticism for many Caucasian visitors precisely because it represents difference perceived to be free of the domestic tensions and fears.' [34] All of these stereotypes and implied associations pose problems for the Australian-Papua New Guinean female dancers as these perceptions are carried over into the late-twentieth-century popular culture.

-

Within the Australian environment there appears to be a conflation of gender and racial stereotypes in combination with colonial attitudes, which in turn influence the Solien Besena and the Motu Kota dance performances and their status in the community. The stereotypes still appear to inform and affect the dancers' performance, sometimes to the detriment of the income and popularity of a dance troupe. Dancers inferred that the performance of their art was partially defined by Australian's positive perceptions of Polynesian and negative attitudes toward PNG One of the Solien Besena dance organisers put it this way: 'The Australians don't want to pay money to see us do our slow traditional dances. They want to see us shake our behinds like the Polynesians. That is not us.'[35] Solien Besena and Papua New Guinean artist, Wendi Choulai succinctly observed:

The result of indigenous people having idealized images about ourselves created for us, affects the way we see ourselves. This is reinforced through the demand of the tourist industry for dancing drum-beating natives in grass skirts. It is interesting to note that when I first 'called' the dancers to the Asia Pacific Triennial (in Brisbane) the women wanted to dance topless as they thought this what would be expected of them and would make them more authentic.[36]

-

In this scenario, the older generation dancers felt obliged to modify their cultural activities, in reaction to the larger Australian society's perception, while the young females were unwilling to make the topless concession and thought it was demeaning. There were also instances in which there were deliberate misinterpretations of the Solien Besena and Motu Koita dance performances in festival programs; and where they were asked to modify their choreography or to make it more exciting by adding risquéé costume modifications. Despite the limitations inherent within this racialised environment, young people still pursued the dance, as their acquisition of cultural knowledge along with the valuing of the activities provided psychological protection and a special sense of worth.

Conclusion

-

Papua New Guinean communities in the urban centres of Australia harbour Solien Besena and Motu Koita women artists who are committed to preserving and fostering traditional art forms from their indigenous cultures. Social clubs or associations have become a catalyst for the formation of dance groups and other culturally-related venues such as 'weekend culture schools', history and arts sessions. For many of the young participants in the cultural activities, the communal organisational process is often more valuable than the final dance production and possible financial gain. The female troupe leaders are highly motivated, despite numerous economic obstructions and a less than understanding Australian society; they are trying to adhere to customary understandings, maintain gender balances and authenticity in the dances.

-

Negotiations for the custodianship of the choreography, music and chants are on-going, shifting with the death of each elder in PNG Contemporary technology has assisted in this matter, providing edited video clips and music through which to teach the next generation, but the balance of gender-based power and the role of select women as temporary knowledge keepers, has yet to be decided. Perhaps customary Soilen Besena and Motu Koita dance in Australia will have to be permanently altered due to the lack of male dancers who have the rights to hold the knowledge. The original choreography was dependent upon a specific balance of males and females. However, if the drought of young males participating in the Australian-based dances continues, then the fate of the Guma Roho and Ita-type dances may be doomed, despite the work of women such as Wendi Choulai and Theresa Barlow. However The Solien Besena people have a finely honed political and economic sense, which encompasses the promotion of their cultural identity. I hypothesise that their constant struggle to validate their cultural practices and identity over several generations and geographic locations, will drive the continuation of dance in Australia.

Endnotes

[1] Sean Mallon, Samoan Art and Artists O Measina a Samoa, Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 2002; Phyllis Hurda, 'Cook Islands tivaevae: migration and the display of culture in Aotearoa/New Zealand,' in Pacific Art Persistence, Change and Meaning, ed. Anita Herle, Nick Stanley and Karen Stevenson, Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 2002, pp. 139–46.

[3] Ranu Ingram James, 'An interview on growing up in Australia,' online: www.mont.org.au/oral_hist/james.html, accessed November 2009. This website is no longer operational.

[4] Charles Seligmann, The Melanesians of British New Guinea, Cambridge: The University Press, 1910; Nigel Oram, Colonial Town to Melanesian City: Port Moresby 1884–1974, Canberra: Australian National University Press, 1976; Epeli Hau'ofa, 'Our sea of islands,' in A New Oceania: Rediscovering our Sea of Islands, ed. Epeli Hau'ofa, Vijay Naidu and Eric Waddell, Suva: University of the South Pacific, 1993, pp. 2–15.

[5] Oram, Colonial Town.

[6] Kay Sydney, 'The languages of British New Guinea,' in the Journal of the Anthropological Institue of Great Britian and Ireland, vol. 24 (1895):15–39; Seligmann, The Melanesians of British New Guinea; Michael Goddard, 'Rethinking western Motu descent groups,' in Oceania, vol. 71, no. 4 (2001): 313–34.

[7] Frank Hurley, Pearls and Savages; Adventures in the Air, on Land and Sea in New Guinea, London: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1924; Oram, Colonial Town.

[8] Oram, Colonial Town.

[9] Interview with Ruth Choulai, Carlton, Australia, 2000.

[10] Oram, Colonial Town.

[11] Wendi Choulai, personal communication, Carlton, Australia, 2000.

[12] Seligmann, The Melanesians of British New Guinea, p. 151.

[13] Seligmann, The Melanesians of British New Guinea ; Frank Barton, 'attooing in South Eastern New Guinea,' in Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, vol. xlviii (1918):22–79; Alfred Haddon, Migrations of Cultures in British New Guinea, London: Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, 1920.

[14] Wendi Choulai and J.A. Lewis-Harris, 'Women and the fibre arts in Papua New Guinea,' in Art and Performance in Oceania, ed. Barry Craig, Bernie Kernot, and Christopher Anderson, Bathurst: Crawford House Press, 1999, pp. 211–17, 310–11 + plates 6–8., p. 213.

[15] Wendi Choulai, 'Indigenous Oceanic design in today's market; a personal perspective, Masters thesis, Melbourne: Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology, 1997.

[16] John Chalmers, Work and Adventure in New Guinea, London: The Religious Tract Society,1900; A.E. Pratt and H. Pratt, Two Years Among New Guinea Cannibals, London: Seeley and Company Limited, 1906; Hubert Murray, Papua and British New Guinea, London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1912; Haddon, Migrations of Cultures in British New Guinea; Alfred Haddon, Head-hunters; Black, White, and Brown, London: Watts, 1932; Cyril Belshaw, The Great Village, London: Routledge and K. Paul, 1957; Bruce Knauft, From Primitive to Postcolonial in Melanesia and Anthropology, Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 1999, p. 151.

[17] Seligmann, The Melanesians of British New Guinea, p. 151.

[18] Barlow, personal communication, Brisbane, 2000.

[19] Barlow, personal communication, Brisbane, 2009.

[20] Barlow, personal communication, Brisbane, 2000.

[21] Theresa Barlow, 'Promotional insert,' in Dance Messages: Quarterly Magazine of the Queensland Folkloric Dance Association, no. 27 (January 2000).

[22] Choulai, 'Indigenous Oceanic design in today's market,' p. 4.

[23] Seligmann, The Melanesians of British New Guinea, pp. 154–55.

[24] Choulai, personal communication, Carlton, 1999.

[25] Choulai, 'Indigenous Oceanic design in today's market.'

[26] Olive Tau, 'Wendi Choulai,' in The Second Asia-Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art Brisbane Australia 1996, South Brisbane: Queensland Art Gallery, 1996, p. 111.

[27] Barlow, personal communication, Brisbane, 2000.

[28] Ruth Turia, personal communication, Canberra, 2000.

[29] Patty O'BrienThe Pacific Muse: Exotic Femininity and the Colonial Pacific, Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2006, p. 166.

[30] Regis Stella, Imagining the Other. Pacific Islands Monograph Series 20, Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 2007; Brenda Dixon Gottschild, The Black Dancing Body: A Geography from Coon to Cool, New York: Palgrave Macmillan 2003; T. Denean Sharpley-Whiting, Black Venus: Sexualized Savages, Primal Fears, and Primitive Narratives in French

Durham :Duke University Press, 1999; Margaret Jolly 'Sites of desire/economies of pleasure sexualities in Asia and the Pacific,' in Sites of Desire/Economies of Pleasure Sexualities in Asia and the Pacific, ed. Lenore Manderson and Margaret Jolly, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1997, pp. 99–122.

[31] Jane Desmond, Staging Tourism: Bodies on Display from Waikiki to Sea World, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999, p. 5.

[32] Ann Stephen, Pirating the Pacific, Sydney: Powerhouse Publishing, 1993.

[33] Cathrine Lutz and Jane Collins, Reading National Geographic, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1993.

[34] Desmond, Staging Tourism, p. 140.

[35] Theresa Barlow, Personal communication, Brisbane, 2000.

[36] Choulai, 'Indigenous Oceanic design in today's market,' p. 15.

|