Kindred Endogamy

in a Bugis Migrant Community

Faried F. Saenong

Introduction

-

A number of Muslim groups in Indonesia valorise forms of endogamy for a range of reasons, with social stratification often playing a key role. Endogamy among male and female descendants of the Prophet Muhammad (Habib and Sharifa) is one prominent example, where the practice is conceived of as conserving the sacred blood of the Prophet.[1] Scholars have long acknowledged that Bugis society in its homeland area has strongly maintained forms of endogamy, particularly among the noble elite. A number have described marriage practice in Bugis society and the role of Islamic teaching. In a doctoral thesis based on fieldwork in Soppeng (South Sulawesi), for example, Susan Millar uses case studies to address most aspects of Bugis marriage, from its social mechanics to its semantics.[2] And Nurul I. Idrus provides an exploration of aspects of Islam and adat in Bugis marriage.[3] Several scholars also deal with the subject as part of their overall works. In Christian Pelras' The Bugis, now regarded as a classic, the subject is described together with a range of kinship and gender issues.[4] Although all three scholars refer to endogamous practices, little attention is devoted to the analysis of endogamy in Bugis society in and of itself.

-

During my fieldwork among Bugis people in the pre-dominantly Makassarese locality of Tompobulu-Bantaeng, I was surprised to discover that many Bugis residents are relatively closely related to each other. This paper explores varieties of familial endogamy among an especially prominent family of Bugis in Tompobulu, focusing on its character, how the practice is conceived, and the circumstances surrounding the practice among different actors.

Endogamy in Bugis society

-

Forms of familial endogamy occur in many societies in insular Southeast Asia, often in close association with issues of rank or status. The practice has been linked to a complex group of beliefs concerning twin-birth, often regarded as acceptable for high status people, but condemned among low status people. Jane Belo's early study on twin births in Bali provides a good illustration of perceptions of twin births among societies in this region.[5] Twins are believed to have contact in the womb of the mother, leading to marital intimacy (incest). However, the abhorrence of this incest is reduced in proportion to the status of the twins involved; among the highest nobility twin birth was to be celebrated. Shelly Errington argues further that close marriage (first cousins) is accepted or even expected among noble families, but is restricted among commoners, citing Clifford Geertz' well-known remark: 'incest is less a sin than a status mistake.'[6] Elsewhere she refers to the 'centripetal impulse to conserve rank' among the nobility by marrying close, thereby conserving rather than diluting noble blood.[7]

-

Traditions of Bugis endogamy are understood as having their roots in early Bugis society. The authenticity of tradition often refers to earliest practices, and in this case endogamy occurs within the La Galigo, a compilation of Bugis myths, stories and poems that is lengthier than the Mahabharata and regarded by some as the world's longest epic. Generally dated to the fourteenth century, most Bugis believe that La Galigo is older. The epic basically tells of the origins of the Bugis world and cosmology through stories surrounding its main character, Sawerigading. The classical Bugis language it uses can hardly be understood by contemporary Bugis; but it has been Romanised and translated into Indonesian and Dutch, among other languages.[8]

-

In one episode of La Galigo entitled 'Ritumpanna Wélenrénngé', there is a notion that the best match among Bugis is intermarriage within a family of the same social stratum. This is labelled mallaibiné massappo siseng or marriage between first cousins. The best known examples are the marriage of Batara Guru and his first-cousin (from his mother's line) Wé Nyelli' Timo', or of Sawérigading with his first cousin Wé Cudai' or of Remmangrilangi' with his first cousin Wé Tenriabéng. Hence, marriage between first cousins (sapposiseng) has been regarded as ideal marriage (assialang marola) among noble lineages (referred to as 'white blood'). Marriage between brother and sister is, on the other hand, viewed as incest and is prohibited, as described in the cases of Sawérigading who once intended to marry his twin sister Wé Tenriabéng, and of Wé Tenrirawé who insisted on marrying her twin brother Pallawagau'.

-

While it remains common among the Bugis nobility to desire their daughter or son to marry a nephew or niece—that is, marriage between first-cousins—Bugis commoners favour marriage between second, third or fourth cousins.[9] Mattulada uses the term assialanna mémeng (literally 'appropriate match') to describe marriage between second cousins, and also third cousins.[10] Haji Bada' Aming, a male Indo' Botting (wedding mother)[11] told me that the purpose of marriage between cousins is ripaddeppé' mabélaé, that is, to 'make the far close by'. This refers to the aim of pulling together or re-tying all extended family members who have 'spread far' in terms of kinship. Embodied in the practice of endogamy for elite and non-elite Bugis alike is a traditional value of maintaining strong familial relationships. This extends also to the level of ethnicity.

-

The inclination of Bugis parents to ethnic endogamy is well encapsulated in a Bugis expression: namu to laing napubainé assala' Ugi' mua (although s/he is to laing [or 'other'], what is important is that s/he is a Bugis). In a sense, marriage between fellow Bugis can still be regarded ultimately as marriage within the family as there is a strongly shared conviction that all Bugis genealogies can be traced to an originating ancestor. If Bugis are all related, then marriage between any two individual Bugis still acts to preserve the value of 'making the far close by'.

The Bugis within Makassar

-

I conducted major fieldwork in Tompobulu in South Sulawesi between 2007 and 2008, followed by several shorter additional visits. Tompobulu is in the Bantaeng District (Kabupaten) and forms an eastern sub-district (kecamatan) covering some 395,000 square kilometres.[12] Situated in a highland area, the name Tompobulu refers to 'the top of the mountain' (tompo': 'top' or 'peak'; bulu': 'mountain') and is used for other settlements elsewhere in highland South Sulawesi, for example in the mountains of Maros and Bulusaraung. Tompobulu in Bantaeng is located in the foot of Bawakaraeng Mountain.

-

Bantaeng in general and Tompobulu in particular are populated predominantly by Makassarese. People of Bantaeng mostly identify themselves as speakers of Konjo, the eastern dialect or accent of the Makassar language.[13] However, there are also clusters of Bugis residing within Tompobulu, especially in the settlements of Banyorang and Ereng-Ereng. These settlements are unusual as Bantaeng is to the east of the traditional Bugis homeland, while Bugis migrants have tended to migrate to the relatively more prosperous areas to the west. The Wajo are famous for an expression, Ia patu muita melle' laopo sompe' ri tana Bare' (you will have a good destiny when you wander to the West).[14] The influx of the Bugis to Bantaeng ought to be viewed in the context of large-scale Bugis migrations beginning in the seventeenth century. As well as settling in Bantaeng, Bugis migrants historically ventured to Samarinda (Kalimantan), Java, Sumatra and Malaysia. Scholars have suggested a number of reasons for these migrations including local warsand the notion of siri'[15] —a complex cultural idea involving aspects of self-dignity and personal honour.[16]

-

A major influx of Bugis to Bantaeng occurred as early as 1608, when La Tenriruwa, the eleventh ruler of Bone, was granted land in Bantaeng by Sultan Alauddin (d. 1639), the thirteenth ruler of Gowa, as recognition for his cooperation with the Makassarese twin kingdom of Gowa-Tallo. La Tenriruwa is considered the first Bone ruler to convert to Islam; the people of Bone rejected his call to convert to the new faith, and La Tenriruwa moved to Pattiro and eventually to Makassar to deepen his understanding of Islam under the supervision of Datu ri Bandang.[17] La Tenriruwa spent the rest of his life in Bantaeng and was posthumously named La Tenriruwa Matinroe ri Bantaeng (who died in Bantaeng). The arrival in Bantaeng of Bugis from Bone under La Tenriruwa has led some scholars to suggest this was the origin of the entire Bugis population in Bantaeng, including the Bugis of Tompobulu. Daeng Rusle, a local researcher, takes this view and also insists that the Bugis community in Tompobulu is comprised mainly of La Tenriruwa's descendants. I encountered a civil servant in Bantaeng who also used the story of La Tenriruwa to argue for this perspective.

-

Bugis residents of Tompobulu, however, trace their own origins largely to Wajo, not Bone. The Wajo are famous for their wandering mentality. Some scholars have acknowledged that the Wajo is a Bugis sub-ethnic group who mostly left their homeland to wander for many reasons. Benjamin J. Matthes once compared the mentality of the Bugis of Bone, Wajo and Soppeng. The Bone, he contended, tended to be farmers, the Soppeng wished to be seekers of knowledge, the Makassar-Gowa liked waging war, while the Wajo were inclined to be entrepreneurs.[18] Zainal Abidin also once quoted a comparison in which the Wajo were destined to be rich, or that the Bone liked to govern, the Soppeng tended to be civil servants, while the Wajo were talented in trade.[19] There is also a famous expression, 'aja' naita bati' napeppeng toGowa, nalewo toBone, nabalu' toWajo, narappa toSidendreng' suggesting that it is extremely hard if we are hunted by the Gowa, besieged by the Bone, sold by the Wajo, and robed by the Sidrap.[20] That was the reason why in the past, the Wajo were widely known as the Chinese of the Bugis for their skill in trade.[21] One of the best ways to apply their trade skill was by wandering somewhere, especially to the West. John Crawfurd once acknowledged that there were about three thousand Wajo in Singapore in the nineteenth century. This fact led him to argue that the enterprising mentality belonged mostly to the Wajo.[22] Jacqueline A. Linetone also argued that the Wajo enjoyed the longest tradition of migration.[23]

-

Some informants, aged between fifty and fifty-five years, reported that the first generation of Bugis from Wajo to migrate to Tompobulu-Bantaeng included their own grandparents. This suggests that Wajo Bugis initially came to the area as late as the second half of the nineteenth century. Historically, Bugis migration tended to occur in large groups led by one or several nobles each with loyal followers and extended families.[24] Patron-client relationships were very strong among South Sulawesi people.[25] The first group of Bone Bugis to settle in the district capital of Bantaeng reflected this general pattern. However, the practice followed by Wajo Bugis in migrating to Tompobulu was quite different, involving family by family migration.

-

According to one informant, H. Zubair, the first Wajo Bugis family to migrate to Tompobulu included the brothers La Mude, Cipu and Rema, along with their extended family, who had heard about the fertility of Tompobulu land. They then moved to Tompobulu and bought lands from the local Makassar on which to plant coffee and cocoa. After this, news of the fertility of Tompobulu soil spread among the Bugis in Wajo. Those who initially migrated to this area invited other families to Wajo, buying land from local Makassars (who reputedly used the proceeds for gambling). In time, a great number of Wajo Bugis arrived in Tompobulu where they remain to this day. Another informant, H. Bada Aming (56) stated that his grandparents and family migrated because of an ongoing and longstanding local conflict in Wajo. Despite belonging to a large and wealthy family, local political instability forced their departure. While initially desiring to remain in Wajo, members of their extended family reported finding a good location at Tompobulu, prompting the decision to migrate permanently to Bantaeng where they too purchased land in Tompobulu for cultivating coffee and cocoa.

-

Importantly, people migrating to other places bring cultural practices and forms of knowledge along with their physical presence, at least initially. Until the 1980s, all Bugis in this area spoke Bugis as the language of day-to-day communication, using Indonesian or Makassarese when speaking to Makassar people. Today, only the older generations of Bugis in Tompobulu still speak Bugis. Bugis children in Tompobulu grow up with the Makassar language, which is taught in Bantaeng's schools. In addition to a local Indonesian vernacular the younger generations speak Makassarese most of the time, although many continue to understand Bugis. Asnawi (33) and Saliha (33) are a couple in Tompobulu who are both Bugis by origin. Asnawi, who was also my host during my research, always spoke in Makassarese to his wife who in turn always replied in Bugis.

-

Despite historical hostilities between Bugis and Makassar polities,[26] the Bugis community in Tompobulu lives peacefully within the indigenous Makassar society. The older generation I talked with during fieldwork did not describe any tensions existing between the two ethnic groups. In their account, the Bugis came with their money and simply followed local rules within the majority Makassar community. The only social tension existing in Tompobulu, according to my informants, involved modernist Muslims represented by Muhammadiyah and traditionalist ones represented by As'adiyah (NU) concerning a range of specific theological issues.

The Tompobulu case

-

A large Wajo Bugis family in Tompobulu was already familiar to me prior to my research. This was the family of Asnawi, a close friend since senior high school in Makassar. After graduating some fourteen years ago, we met again in Tompobulu where he was born and now resided. Asnawi became my host and a dependable informant. His relations, Asnawi and Richwan, were also classmates in senior high school. During my fieldwork I was soon struck by the extent to which members of Asnawi's extended family, many of whom occupied significant roles within their Tompobulu communities, married relatively near relatives.

-

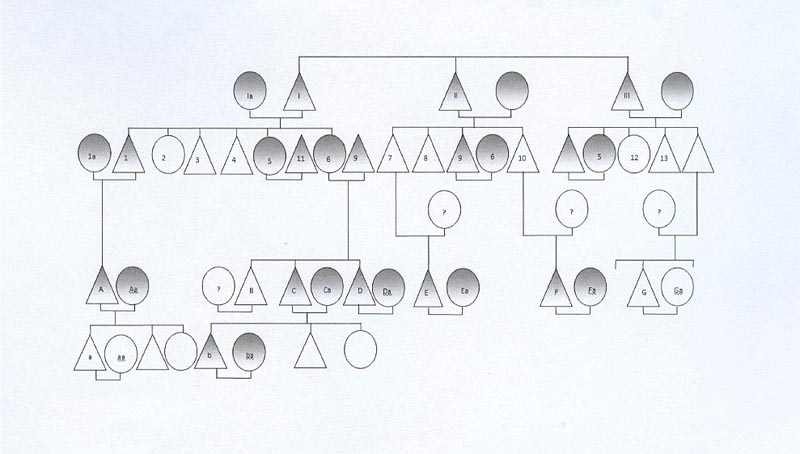

As shown in the family chart below, Zainal (a) and Asnawi (b) are second cousins as their fathers H. Husain (A) and H. Zubair (C) respectively are first cousins. Richwan (G) is related as a distant uncle to both Zainal and Asnawi. Richwan is older by one generation, but younger by age. He is also the second cousin of Zainal's and Asnawi's father. Their familial or kin relationship meets in La Mude (the great grand-father of Zainal and Asnawi) and Rema (the grand-father of Richwan).

-

For similar reasons, I found the kin relationship between H. Husain (A), Bada' Aming (E), Daeng Sori (F), H. Syuaib (D) and H. Zubair (C) interesting (all five play important religious and cultural roles in Tompobulu). As shown in the chart, they are all cousins. H. Husain is second cousin to Bada' Aming and Daeng Sori, as well as to H. Syuaib and H. Zubair. Bada' Aming and Dg. Sori who are first cousins are second cousins to H. Zubair and H. Syuaib, who are first cousins. The kin relations existing between these individuals reflect the Bugis prescription among commoners for marriage within one's extended family. Bada' Aming and Dg. Sori are married to Dg. Satu and Dg. Aisyah respectively who are their maternal second cousins, while H. Zubair and H. Syuaib have marriages with Hj. Rahmah and Hj. Syamsiyah respectively, who are their maternal first cousins.

-

Note that familial or kindred endogamous marriage is more prevalent within the older generation. As shown in the family tree, there are at least three couples that had endogamous marriages, all of which were to first cousins. H. Cangkelo (1) was married to his maternal first cousin, Hj. Bare (5) to H. Sanusi (11), and Hj. Halimah (6) to H. Saraka (9). They are among the second generation of Wajo Bugis residing in Tompobulu. H. Syuaib, one of the third Bugis generations living in Tompobulu, explained that the first generation Bugis families in Tompobulu were also a kin group in Wajo. He found that his grand-parents and other families in Tompobulu had family ties, even if they could not be confirmed in their particulars.

Figure 1. Kindred endogamy in a Tompobulu Bugis family

Description

I (La Mude) = Ia (Indo Dala/cousin)

II: Cipu

III: Rema

1 (H. Cangkelo) = 1a (H. Badra/2nd cousin)

2 (Kasymah)

3 (H. Hasan)

4 (H. Beddu)

5 (Hj. Bare) = 11 (H. Sanusi/1st cousin)

6 (Hj. Halimah) = 9 (H. Saraka/1st cousin)

7 (H. Kube Cambang) = Hj. Hadra/cousin

8 (Made Aming)

9 (H. Saraka) = 6 (Hj. Halimah/1st cousin)

10 (H. Mu'mining)

11 (H. Sanusi) = 5 (Hj. Bare/1st cousin)

12 (Saripa Lintang)

13 (Sagire)

14 (H. Hamid) = Hj.)

|

A (H. Husain) = Aa (Hj. Badra/2nd cousin)

B (H. Taju)

C (H. Zubair) = Ca (Hj. Rahma/1st cousin)

D (H. Syuaib) = Da (Hj. Syamsiyah/1st cousin)

E (H. Bada Aming) = Ea (Dg. Satu/2nd cousin)

F (Dg. Sori) = Fa (Dg. Aisyah/2nd cousin)

G (Richwan Hamid) = Ga

a (H. Zainal Abidin) = aa (Indah)

b (Asnawi) = ba (Saleha/cousin)

|

-

It is worth noting that Asnawi's parents, H. Zubairi and his wife Hj. Rahma are respected merchants with considerable cocoa and coffee plantations in the Tompobulu area. Indeed, Hj. Rahma works independently as a merchant, with shops in Tompobulu markets. Their relatives, H. Husain, Bada' Aming, Daeng Sori, H. Syuaib and H. Zubair all play important religious and cultural roles in Tompobulu. Ustas Husain, the imam of Desa Labbo of Tompobulu, is an esteemed Muslim scholar who is responsible and trusted in relation to Islamic-related matters in the village—such as marriage, birth, circumcision, death, building new houses and so forth. He also provides problem-solving and conflict-resolution services for families. This happens particularly in relation to cases of elopement (silariang, nilariang or erangkale). Under the strong application of adat (customary) law, his house is a secure place for any eloping couples to seek refuge. He is a graduate of Asádiyah (Wajo) which is the oldest and best-regarded traditional pesantren (Islamic boarding school) in South Sulawesi. He is literate in Arabic and can therefore read conventional and acknowledged sources of Islamic law.

-

H. Syuaib, is a local educator and preacher who supervises some Islamic schools in Tompobulu and Bantaeng. He is among the locally respected people who founded As'adiyah pesantren in Tompobulu. He is a graduate of As'adiyah in Sengkang, Wajo. Also acting as headmaster, he is now running his own school named Madrasah Aliyah Asádiyah in Desa Labbo. He delivers religious speeches in mosques, not only in Tompobulu, but also in mosques around Bantaeng. In addition to this main job, he is also running his own business in construction materials. He has a shop, next to his house in Banyorang, where he sells construction materials to the people of Tompobulu.

-

H. Bada' Aming, is a local male Indo' Botting, responsible for culture or tradition-related matters in the context of weddings, who also provides services outside Bantaeng. One of his main jobs is to remind the groom of basic Islamic matters including physical purification (tahara). He usually briefs the groom on these matters with reference to a very basic textbook of Islamic law entitled Safina al-Najah. And Daeng Sore is a respected To Macca, that is to say, a shaman who is frequently visited by villagers or even people from elsewhere for consultation about life matters. His house in the highland of Pattiro is a place where many people come to seek advice for their problems. In addition to his job as a farmer, he claims to possess supernatural knowledge. He practices certain amalan (religious practices) that, according to him, continuously enables him to read something behind the curtain that lay people are unable to do. He claims that he is visited not only by local Bantaeng, but also by people coming from Bulukumba, Makassar and Java.

-

The general objective of kindred endogamy in wider Bugis society is to maintain family closeness. Parents-in-law who are siblings or cousins are already close and familiar. The couple and both their families do not need time to come to know one another as they are not to laing (lit. 'other people', i.e. not members of a kindred network). A common Bugis expression is worth quoting in this regard: 'It is much better to marry among us, otherwise, they will behave as others' (Makessimmuatoitu ko padaidi'ki' siala, nakko to laing, to laing mutotu sipa'na)—'others' here mean not the same as family. In a similar fashion, a Bugis visitor to Canberra in 2008 told me that she would be happy to marry her daughter to her nephew as she expects a son- or daughter-in-law to assist and care for her, that is, to conduct themselves as family members and not as outsiders.

-

Narratives surrounding Bugis marriage demonstrate the great importance of family closeness. The Bugis language counterpart for marriage, siala (lit. to take each other), does not refer to only the relationship involving the new husband and wife, but also to the families of the bride and the groom who must do the same. As well as binding a husband and wife, marriage binds both of their families. In her study of Bugis marriage, Idrus demonstrates this view, exemplified in common advice from Bugis parents: 'If you look for a wife, look for the one who loves your family, because for us the Bugis, if we marry, the family [also] do so' (nakko sappa'ko bainé, ia mélorié to ri seajimmu, nasaba' idi'tu to ugi'-é nakko bottikki, bottittoi tu seajingngé).[27] Although this advice is addressed to the man or prospective husband, it applies also to any Bugis woman looking for a husband. Clearly, one straightforward means to implement this advice is to practice familial endogamy.

-

At least three patterns shape kindred endogamy within contemporary Bugis society. This first involves 'child marriage' or 'matching'. Child marriage or underage marriage is conducted by parents of both families who simply match their children. The children are informed that they have been matched or 'married' and that therefore, they should maintain the relationship. Secondly, Bugis strongly prefer kindred marriage within the same generation. Marriages between different generations (uncle and niece, for example) are condemned. Thirdly, Bugis traditionally tend not to marry people of other villages for financial reasons. In addition to dowry and other wedding expenses, a man intending to marry a woman of another village was once expected to pay what is called pallawa tana.[28] Although this specific form of payment is no longer applicable in the contemporary period, some retain respect for the cultural tradition, and demonstrate this by avoiding the situation or paying what might be considered a 'formality' fee. Bada' Aming told me that in the past, the Bugis practice of cross-cousin marriage was one way to avoid the pallawa tana fee. And another informant in Makassar confirmed that there are older Bugis who are aware of the practice still occurring.

-

Among Bugis noble or 'white-blood' offspring, marriage between sapposiseng first cousins overtly aims to preserve the purity of noble blood. Endogamy in the form of marrying exclusively within a high social strata or caste is widely associated with issues of purity and impurity linked to maintaining the exclusivity of social status.[29] Errington adds that endogamy among the Bugis nobility is also about the accumulation of spiritual power which they believe naturally lies inside their blood.[30] Kathryn Robinson notes:

[D]ifferentiation of rank [is] based on the notion of the noble strata descended from ancestral beings who established the ruling lines (tomanurung).… High noble descent is also associated with a high degree of spiritual purity, expressed in terms of a balance of bateng and lahireng (inner experience and worldly accomplishments).[31]

In other words, the divine power and supremacy of Tomanurung origin should not be soiled or diluted by inter-marriage with commoners.

-

But another concrete objective of the practice is to avoid the dissipation of family property. A male Indo' Botting (marriage ritual expert) in Tompobulu linked familial endogamy to just such a rationale, stating it is practiced 'in order not to break the property (supaya de'na mareppa' pusakae). The impetus to maintain possession of property within the family among Bugis people in Tompobulu is illustrated also in selling land. In the event that a family is forced to sell land, they will always offer it initially to close family. Or family members will be the first to make an approach to purchase in order to save the land from being transferred to To Laing (Others). My fieldwork host once noted: 'My grandparents never sold land to To Laing in order to keep the lands in family possession.' Brian Schwimmer argues that in general, parallel cousin marriage is often linked with the maintenance of property within the family line.[32] A similar practice exists in Java, where Geertz reports that forms of familial endogamy among peasant landowners leads to the formation of a group of village leaders (lurah desa) who are brothers, as are their staff.[33]

-

In my analysis, I would argue that endogamy is supplementing a strong emphasis on bilateral descent within Bugis society. Despite the fact that Bugis tend toward patrilinealism in their political system, they have one of the few traditional political systems that also permitted and acknowledged female leadership, which has lent support to claims of a bilateral kinship system within Bugis society.[34] Notwithstanding James J. Fox's examination of elite patrilinealism as a variant in bilateral systems,[35] I suggest that familial endogamy within Bugis society reflects the social importance given to bilateral kin. The relatively proximal relationship between families does not create distance, and the relative supremacy of one family over another, together with their social locations, has not been an issue within Bugis families, except perhaps in the formation of patron-client relationships.

-

Of interest here is the issue of post-marital residence in Bugis marriage. Uxorilocal residence, that is, where a married couple resides with or near the wife's parents, remains the primary option for most couples.[36] In Bugis society, a daughter, especially if she is the only or the youngest daughter, is supposed to serve her parents even following her marriage. According to a Tompobulu informant, a major part of the mother's inheritance will be directed to the youngest daughter. She explained that as parents have been responsible to give care to their children, the last or youngest daughter is then supposed to take care of their elderly parents. My Tompobulu informant's own hope was that her youngest daughter would marry someone from her family, and that they would be happy to stay in her large house, or at least in a house nearby. In deciding on post-marital residence the new couple may stay adjacent to either the wife's father's brother or the wife's father's sister; provided they remain close to the wife's kin the decision is not problematic.

-

Nonetheless, some newlywed couples may well feel compelled to live with or near the husband's family (i.e. reside virilocally). The same informant pointed towards one house where a newly married couple was living. The house belongs to the husband, a prosperous widower who had re-married a nineteen-year-old woman. The situation was comparable to that described by Pelras in which a newly wed couple chose to live in the vicinity of their patron's family in order to ensure access and provide support to them.[37] Increasingly, depending on their particular circumstances, newlywed Bugis couples are choosing to reside with or near either the husband's or wife's parents (ambilocal residence), or even away from either the husbands' or wife's natal household (neolocal).

Concluding remarks

-

Traditions of familial endogamy are still relevant to contemporary Bugis society, especially the Bugis community in Tompobulu-Bantaeng where I found marriages between relatives. Older generations of Bugis still practise endogamy, but the way they negotiate this practice is variable. Early Bugis practice more strictly endogamous marriage, while contemporary Bugis may extend the limit of endogamy, from within close and extended families (cousins) to Bugis of the same village, and finally to ethnic Bugis generally. In other words, the practices of more restricted familial or kindred endogamy have shifted over time to sub-ethnic and finally to ethnic endogamy.

-

This might be a distinct characteristic of Bugis endogamy compared to similar practices in other societies. It is interesting to compare the Bugis community in Bantaeng with those in Johor and Perak, both in Malaysia. In contrast with Narifumi M. Tachimoto's account of the Bugis community in Johor, the Bugis of Tompobulu adhere to a variety of familial endogamy between those with a familial relationship. The Bugis community in Johor, meanwhile, follows what Tachimoto terms 'ethnic endogamy' where a Wajo Bugis is permitted to marry either to a fellow Wajo, a Bone, Soppeng or Luwu Bugis.[38] To put it another way, John F. McNair who did ethnographic fieldwork in Perak reported that Bugis in Perak avoided marriage and kept distinct from other groups of people around them.[39] Taking Tachimoto's study on Bugis community in Johor and McNair's report on Bugis in Perak into account, it is clear that the Bugis practice of endogamy may extend to marrying within a cultural and linguistic group. This is consistent with their adaptation to modernity.

Acknowledgements

An earlier version of this paper was presented at the 9th Women in Asia (WIA) International Conference in Brisbane, 29 September – 1 October 2008. I would like to thank the Department of Anthropology (CAP) ANU and the ARC Asia Pacific Futures Research Network Southeast Asia Node for the grant. I am grateful to scholars and colleagues who have made significant contributions to this paper; Kathryn Robinson, James J. Fox, Campbell Macknight, Andrew McWilliam, Phillip Winn, anonymous reviewers, Eva F. Nisa, Asnawi Zubair and his family, Zainal Abidin, Saenong Ibrahim, Kelly Piers and others. All errors, however, are completely mine.

Endnotes

[1] See, for example, Frode F. Jacobsen, 'Marriage patterns and social stratification in present Hadrami Arab societies in Central and Eastern Indonesia,' in Asian Journal of Social Science, vol. 5, no. 35 (2007): 473–87.

[2] Susan B. Millar, Bugis Weddings: Rituals of Social Location in Modern Indonesia, Berkeley: Center for South and Southeast Asian Studies, University of California, 1989; 'On interpreting gender in Bugis society,' in American Ethnologist, vol. 10, no. 3 (1983): 477–93; 'Bugis society: given by the wedding guest,' Ph.D. thesis, Faculty of the Graduate School, Ithaca, NY.: Cornell University, 1981.

[3] Nurul I. Idrus, 'Behind the notion of siala: marriage, adat and Islam among the Bugis in South Sulawesi,' in Intersections: Gender, History and Culture in the Asian Context, issue 10 (2004), URL: http://intersections.anu.edu.au/issue10/idrus.html, site accessed 12 August 2008.

[4] Christian Pelras, The Bugis, London: Blackwell, 1996.

[5] Jane Belo, 'A study of customs pertaining twins in Bali,' in Traditional Balinese Culture, ed. Jane Belo, New York: Columbia University Press, 1970 [1935], pp. 3–56.

[6] Shelly Errington, 'Incestuous twins and the house societies in insular Southeast Asia,' in Cultural Anthropology, vol. 2, no. 4 (1987): 403–44, p. 403.

[7] Errington, 'Incestuous twins,' p. 425.

[8] For more information regarding La Galigo, see, for example, Andi Zainal Abidin, 'The I La Galigo epic cycle of South Celebes and its diffusion,' in Indonesia, vol. 17 (1974): 160–69; S. Koolhof, 'The "La Galigo"; a Bugis encyclopedia and its growth,' in Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, vol. 155, no. 3 (1999): 362–87.

[9] Millar, Bugis Weddings, p. 36.

[10] Mattulada, Latoa: Satu Lukisan Analisis terhadap Antropologi Politik Orang Bugis, Ujung Pandang: Unhas Press, 1995, p. 44.

[11] Indo' Botting literally means wedding mother who is in charge of culture-related issues of marriage. They are very often women. Sometimes, however, there are Ambo' Botting (wedding father) and Indo' Botting for the groom and the bride respectively. People in Tompobulu keep calling H. Bada' Aming Indo' Botting, using it generically, as he is also often responsible to both bride and groom.

[12] Badan Pusat Statistik (BPS), Bantaeng dalam Angka, Bantaeng: BPS, 2007.

[13] Thomas Gibson, 'Childhood, colonialism and fieldwork among the Buid of the Philippines and the Konjo of Indonesia,' in Enfants et sociétés d'Asie du Sud-Est, ed. J. Koubi and J. Massard, Paris: L'Harmattan, 1994, pp. 183–205.

[14] Andi Zainal Abidin, Capita Selecta Sejarah Sulawesi Selatan, Ujung Pandang: Hasanuddin University Press, 1999, pp. 183 and 202.

[15] John Bastin, 'Problems of personality in the reinterpretation of Modern Malayan History,' in Malayan and Indonesian Studies, ed. J. Bastin and R. Roolvink, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1964: 141–55, p. 145; Leonard Andaya, 'Bugis migration in the late-seventeenth century,' unpublished essay, 1970, p. 13; Andi Zainal Abidin, Persepsi Orang Bugis-Makassar tentang Hukum, Negara dan Dunia Luar, Bandung: Alumni, 1983, p. 56.

[16] Henry T. Chabot, 'Bontoramba, a village in Goa, South Sulawesi,' in Villages in Indonesia, ed. Koentjaraningrat, Ithaca NY: Cornell Press, 1967, pp. 189–209; Pelras, The Bugis; Millar, Bugis Weddings; Mattulada, Latoa.

[17] Datu ri Bandang is one of three Datu (Datu ri Patimang and Datu ri Tiro) who are conventionally acknowledged as the earliest propagators of Islam in South Sulawesi in the early seventeenth century. They share duties by residing in the three different places that are named after them.

[18] Benjamin J. Matthes, as cited in Abidin, Capita Selecta, pp. 176–77.

[19] Abidin, Capita Selecta, p. 184.

[20] Abidin, Capita Selecta, p. 184.

[21] Abidin, Capita Selecta, p. 185.

[22] John Crawfurd, A Descriptive Dictionary of the Indian Islands and Adjacent Countries, London: Bradbury & Evans, 1856, p. 441, as cited in Abidin, Capita Selecta, p. 178.

[23] Jacqueline A. Lineton, 'An Indonesian society and its universe: a study of the Bugis of South Sulawesi (Celebes) and their role within a wider social and economic system,' Ph.D. thesis, Department of Anthropology SOAS, London: University of London, 1975, p. 199.

[24] Lineton, 'An Indonesian society and its universe,' pp. 176–78.

[25] Heddy Shri Ahimsa-Putra, Minawang: Hubungan Patron-klien di Sulawesi Selatan, Yogyakarta: Gadjah Mada University Press, 1988.

[26] H.J. Friedericy, 'De standen bij de Boegineezen en Makassaren,' in Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde van Nederlandsch-Indië, no. 90 (1933), pp. 447–602; Mattulada, Menyusuri Jejak Kehadiran Makassar dalam Sejarah, Ujung Pandang: Bhakti Baru, 1982, pp. 14–15.

[27] Idrus, 'Behind the notion of siala.'

[28] Pelras, The Bugis.

[29] John H. Beattie, Other Cultures: Aims, Methods and Achievements in Social Anthropology, London: Routledge, 1964, p. 121.

[30] Shelly Errington, '"Siri'", Darah dan Kekuasaan Politik di dalam Kerajaan Luwu Zaman Dulu,' seminar paper on Siri and it's problems in South Sulawesi, Ujung Pandang, 13 July 1977, p. 52.

[31] Kathryn Robinson, Gender, Islam and Democracy in Indonesia, New York: Routledge, 2009, p. 26.

[32] Brian Schwimmer, 'Kinship and social organization: an interactive tutorial, 1995–2003,' in University of Manitoba Website, URL: http://www.umanitoba.ca/faculties/arts/anthropology/tutor/marriage/endogamy.html, accessed 23 September 2010.

[33] Hildred Geertz, The Javanese Family: A Study of Kinship and Socialization, Glencoe: The Free Press, 1961.

[34] Anthony Reid, Southeast Asia in the Age of Commerce: The Land below the Winds, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988, pp. 169–72; Millar, Bugis Wedding.

[35] James J. Fox, 'Austronesian societies and their transformations,' in The Austronesian: Historical and Comparative Perspectives, ed. Peter Bellwood, James J. Fox and Darrel Tryon, Canberra: ANU Press, 1995, pp. 229–44.

[36] Robinson, Gender, Islam and Democracy in Indonesia, p. 27; Pelras, The Bugis, p. 156.

[37] Christian Pelras, 'Patron-client ties among the Bugis and Makassarese of South Sulawesi,' in Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde. , vol. 156, no. 3 (2000): 393–432, p. 398.

[38] Narifumi M. Tachimoto, 'Coping with the currents of change: a frontier Bugis settlement in Johor, Malaysia,' in Southeast Asian Studies, vol. 32, no. 2 (1994): 197–230, pp. 214–15.

[39] John F. McNair, Perak and the Malays: Sarong and Kris, London: Tinsley Brothers, 1878, p. 131.

|