Continuities and Discontinuities:

Malay Workers and Migrant Workers in the Manufacturing Industries

Vicki Crinis

Introduction

-

In Malaysia, the management of migrant workers interrelates with the management of labour for the export industries. The export sector faces high levels of competition from low wage countries such as Bangladesh, China and Vietnam. Employers find migrant workers, especially females, to be a cheaper and more 'docile' form of labour than are Malaysian workers.[1] The vulnerability of female migrant workers makes them a more manageable workforce, compared to citizens and male migrant workers.[2] According to David Harvey, flexible accumulation requires flexible workers, which means a greater use of contracts, overtime and temporary migrant workers.[3] Both capital and the state benefit because the use of flexible workers implies that workers are temporary and can be disposed of when the demand for labour declines. Local labour organisations and NGOs also argue that it is not so much low wages that employers seek, but the flexibility of hiring and firing at will. This means that Malaysian workers are not affected. Migrant workers keep the export economy afloat by performing the low paid work Malaysian workers shun. To date, migrants in the manufacturing industries comprise about 36 percent of the authorised migrants working in Malaysia.[4] As Juanita Elias has noted in her article, Malaysia is one of the most successful developing countries in the world yet it has continued to depend on migrant workers to fill low-paid manufacturing industry jobs.

-

Immigration policies are in place to assist the state to provide industry with 'docile' workers. Under these policies, migrant workers are not entitled to social benefits and do not have the right to citizenship, family unification or to join associations. They are unable to marry locals and remain in Malaysia. Women are not allowed to get pregnant while working in Malaysia. As a result, female workers are obliged to have annual gynaecological tests, and if found to be pregnant, they are immediately deported. The threat of dismissal and deportation acts to discipline migrant contract workers, especially those in debt to recruitment agents and families. Despite the fact that Malaysia is a labour receiving country the government has signed, but not ratified, the international human rights conventions pertaining to the well-being of migrant workers and their families.

-

In spite of the fact that migrant workers have diverse experiences working in Malaysia, they all live within a complex range of discourses which devalue their work.[5] Migrants view border crossings as new social, cultural and economic experiences, and as a way to earn money, to learn new skills, to shop for consumer goods, to meet new people, to speak new languages and to escape dysfunctional relationships in their own country. Yet in community discourses migrant women are situated in narratives that sway between docile and sensual, as opposed to male workers who are perceived to be unruly, violent or weak in terms of their masculinity compared to other ethnicities. It is important to investigate the ways gender is written about and employed in the management of migrants but, more importantly, how workers resist and struggle against national surveillance and capitalist discipline.

-

Any story of women's work in the global export manufacturing sector must be grounded in the past. As Christine Chin has demonstrated when discussing migrant domestic workers in Malaysia, migration, the state and female workers have a long history. This article places migrant workers in a longer history of women and work in the manufacturing industries. It questions the connections between Malay female factory workers in the 1970s and 1980s with migrant labour in Malaysia today. There is no study to date that traces the continuities and discontinuities between Malay migrant workers in the early industrialisation period and transnational migrant workers in the manufacturing industries today. While the study is largely centred on female workers, statistics in Malaysia rarely distinguish between male and female, and in some factories, employers recruit whatever workers are available, thus blurring the sexual division of labour to some extent.[6] So the term migrant worker will be employed unless specifically related to female workers. This article, based on qualitative research,[7] media and textual analysis, is framed from the position of Aihwa Ong, who borrows from Michel Foucault's concept of bio-power to highlight the state's organisation and control of young female and migrant bodies for the economic development of the nation.[8] I discuss how subjects assess their own behaviour to fit in with notions of the good worker and/or how they resist their objectification and struggle against state and capitalist discipline.

Malay female workers in the export manufacturing industries

-

In the following section I provide a brief outline of the history of export manufacturing in Malaysia, industrial modernity and the consequences for Malay factory workers. The New Economic Policy (NEP) of 1971 (introduced after the race riots of 1969) focussed on changing the structure of the community. The policy had two main objectives. The first was to eradicate poverty by raising income levels, thus increasing opportunities for all peoples of Malaysia. The second was to restructure society in order to increase the economic standing of Malays by preferentially bringing them into the modern sector. The new government sought to give them a privileged position in the development process. Also, by shifting from import substitution industrialisation policies to export-oriented policies, the government hoped to create more jobs as a response to the high levels of Malay unemployment and poverty.[9]

-

While the NEP policies sought to provide employment for peoples of all walks of life, the newly established manufacturing industries employed more female labour than male labour. By the late 1970s, some eighty thousand Malay kampong (village) women between the ages of sixteen and twenty-four had been transformed into factory labourers.[10] The government had reduced Malay women to instruments of production to achieve the goals of the country.[11] The government looked at short term goals and did not consider the women workers' welfare or their long-term job prospects. As Malay women were expected to marry and produce children, their role in the workforce was perceived as temporary. But promoting Malay interests and keeping Malay women in low-paid manufacturing industries to sustain industrial development was problematic. The state initially overcame these contradictions by framing women in discourses about Asian women's 'biological' attributes such as small hands, nimble fingers and docile disposition.[12]

-

While the genetic characteristics of young female workers were embedded in state discourses of women and work, the community viewed female rural-to-urban labour migration and women's living away from home in different ways. In the eyes of the community, traditional Malay values were threatened because young women were perceived as becoming 'western,' a term which carried connotations of sexual promiscuity and the corruption of Islamic values. The capitalist print media represented women's bodies as sexual commodities which caused considerable concern to parents and the community at large. Women's bodies became part of newspaper reporting for the simple reason that the newly established industrial landscape exposed certain features of modern lifestyles that were frowned upon within the Islamic Malay culture.

-

Ong's study, Spirits of Resistance and Capitalist Discipline, demonstrated that sexualising the female factory worker had larger ramifications for women and work.[13] She revealed how Malay cultural definitions of its females served a specific purpose in disciplining factory women in the workforce.[14] According to Ong, discourses regarding female workers' morality were channelled into factory discipline. Religious and capitalist values complemented each other in this context; good Muslim girls were perceived as good workers who did not socialise with men or engage in social activities outside the home or the factory, and this notion accorded with management views to enhance workers' productivity and factory output.

-

Factory management was well aware that modern Islamic nationalism was growing in Malaysia and, as part of their human resource programmes, they incorporated systems that would help in the control of Malay workers. This was particularly relevant as women workers were not in any way the 'docile' workers they were claimed to be.[15] More than 60 percent of the women interviewed by Jamilah Ariffin claimed that mass hysteria occurred at least once at their factories.[16] Ong investigated these conditions from both a cultural and a political economy position which viewed the hysterical outbursts as the resistance tactics of young Malay women. Ong revealed how the socio-economic power structures become obscured when women are framed within the discourses of the female hysteric (or inherent Malay excitability).[17] Also, because women workers were labelled as hysterical, their use of such outbursts as a disruptive device against the dominant practice of patriarchal capitalism became invisible. During this period, young factory workers continued to provide vital income to subsidise their families' incomes, but the discourses pertaining to factory workers and their carnal behaviour acted as a control mechanism for women who were concerned about their moral reputations. Thus, cultural norms provided a strong area of control over women's behaviour that could be used within religious, industrial, political and nationalist agendas.[18]

The high-tech worker and the invisible factory worker

-

In recent times, most people within Malaysia (and many outside) would argue that the modernisation strategy based on foreign direct investment and export-oriented industrialisation has worked in Malaysia, and women have benefitted from government policies. Malaysia is a success story when it comes to industrialisation, modernisation and development, evident in the Asian economic crisis of 1997–98.[19] Thus modernisation and economic development give credence to Maznah Mohamad's argument that women workers of today are a far cry from the 'hysterical' workers in the manufacturing industries in the 1970s.[20] Factory women can now work in a more flexible environment, and some, although this is only possible for a select few who have access to long-term employment, have the opportunity to increase their technological skills and move to skilled and supervisory positions. Mohamad's study of the electronics industry has demonstrated that this is largely the result of a shift in the industry from labour-intensive production of microchips to one where production technology has become more automated, and incorporates flexible production techniques. This is particularly evident in the components sub-sector with the introduction of 'just in time' and 'quality control circle' methods.

-

The clothing, textile, and electronics industry (especially the semiconductors and electronic consumer goods section) are highly globalised. While these industries have had significant growth over the twenty-year period from the 1980s to the 2000s, they are well known for the periodic retrenchment of workers. Their employment patterns are unstable and they are subject to crises of over-production. During the Asian economic crisis of 1997–98, thousands of workers were laid off in the manufacturing industries.[21] In December 2001, it was reported that women accounted for more than 53 percent of workers retrenched during the year. About thirty-eight thousand women, mostly production workers in the electronics industries, were retrenched from January 2001 to January 2002.[22]

-

Subsequently, Malay women avoided the factories and found jobs in the higher-paying government, professional and business sectors (although this largely applies to well-educated rather than poor women) and labour shortages were registered in the low paid factory sectors. Since then, Malaysian factory workers have been largely invisible in government rhetoric, firstly because it is important for the government's development profile that labour-intensive industries become invisible. Given that labour-intensive industries are perceived to be 'starter' industries for developing economies, these industries supposedly fade out to become 'sunset industries' as the developing country reaches a higher stage of development. However, Malaysia's garment, textile and electronic industries are not 'sunset' industries. Although they may be at the crossroads, these industries, especially the electronic industry, continue to contribute to the Gross Domestic Product (GDP).[23] During the 2000s, increasing levels of global competition under neoliberal policies meant employers and companies sought flexible workers and more informal working conditions. This allowed for worker intensification or worker dismissal according to labour demands. A government practice to help industries in Malaysia cope with high levels of global competition is to condone the employment of low-paid unskilled migrant workers.

Migrant workers in the 'sunset' industries

-

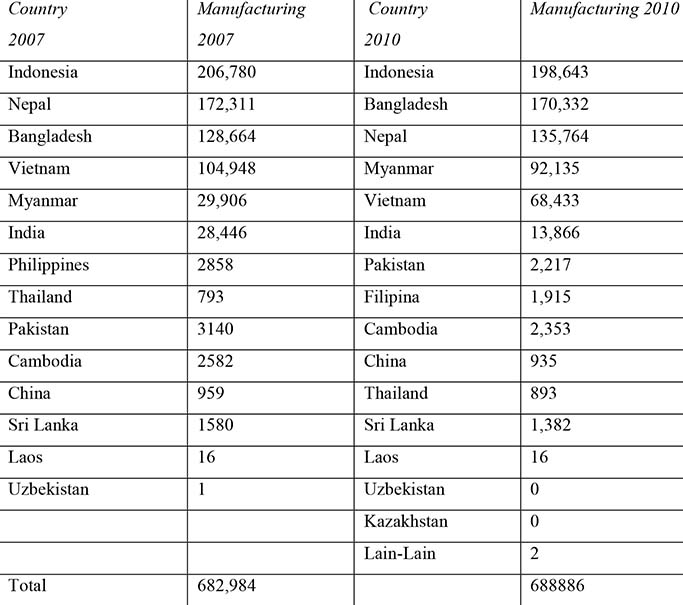

In 2004, the government signed Memoranda of Understanding (MOUs) with various countries to legally recruit female and male guest workers to fill the jobs Malaysian women no longer wanted. By 2007 over 600,000 migrant workers were employed in the electronics, clothing, textile and food packaging factories. As can be seen from Table 1, migrant workers are recruited from a large number of countries. The largest numbers of foreign workers employed in the manufacturing industries are from Indonesia, followed by workers from Bangladesh, Nepal, Myanmar, Vietnam and India. The government is constantly juggling the recruitment of different ethnic groups according to how they fit into the social environment in the factory and public arena. The value of a certain ethnicity, such as the perception that one is passive while another is disruptive, determines the conditions under which migrant workers continue working in Malaysia. Factory employers generally prefer to hire migrant workers over Malaysian workers, and female migrant workers over male migrant workers. If female workers are unavailable, Nepalese male workers are preferred over other male migrant groups because they are perceived to be more 'docile.' Nepalese are often the victims of crimes because they are supposed to be timid compared to other male ethnic groups.[24] Burmese workers are professed to be quieter than Vietnamese workers but unless they are experienced in industrial work, employers prefer Vietnamese. In Malay-owned companies employers prefer to employ Indonesian male workers over Indonesian female workers, because male workers are seemingly less troublesome. According to these employers, female workers may become pregnant and leave the factory leading to financial loss for the employer.

Table 1. Comparison of Overseas Migrant Workers employed in 2007 and 2010

Source: Malaysian Bar Council and Malaysian Textiles Manufacturing Association

-

During the Global Economic Crisis (GEC), the numbers of migrant workers declined by 300,000 because expiring work permits were not renewed and the government restricted the further intake of migrant workers. By the end of 2009 manufacturers had to increase wages to entice Malaysian workers.[25] During the period of labour shortage, the wages of manufacturing workers rose from M$450 (US$130) a month in 2008 to M$650 (US$185). In response to pressure from manufacturers, the Malaysian government allowed electronics and textile firms to resume recruitment of male and female migrant workers.

Perceptions of female migrant workers: docile to disorderly?

-

Immigration policies place female migrant workers in relatively powerless positions in the nation and the workforce. To use an example, workers usually sign a contract to work for one employer, and their passports are held by management. In this context they have little hope of moving to another employer and must follow the terms of the contract or risk termination of employment and exportation.[26] But workers are not as docile as management would like, or otherwise there would be no need for employers to hold workers' passports. Female workers have a certain level of bargaining power especially in times of labour demand. Firstly, human resource managers have great difficulty finding suitable workers to fill factory vacancies. In this context workers who meet the employer's expectations during the contract period are not likely to be laid off; in fact they are more likely to be offered a further contract.[27] Some workers interviewed had worked for between five and seven years in the same factory. Second, employers have a hard time replacing experienced migrant workers. Aside from the expense and the time between application and the arrival of the women, employers need to invest in the skilling of female workers to complete orders for 'just in time' delivery dates. Brand name buyers insist suppliers deliver to the wharf on time or else they charge the supplier the transport costs for air freight. Workers have the power to disrupt 'just in time' production by holding stop work meetings, addressing management over hostel safety or by engaging in more clandestine actions that disrupt and hold up 'just in time' production and deliveries.

-

Despite their bargaining power in the factories, which is somewhat limited, migrant workers have to struggle against narratives that situate workers as problematic. In Malaysian community narratives, female migrant workers, like their Malay predecessors, are viewed as engaging in licentious behaviour. In the local newspapers, claims about Chinese female migrants preying on and paying Malaysian men to marry them provoke tensions between migrants and citizens.[28] In these stories, migrant females pose a danger to family stability. In other narratives, migrant workers substitute low paid factory work with sex work.[29] Malaysians and procurers obviously believe that some female workers can be seduced into seeking higher paying jobs in the entertainment industry. Stickers advertising lucrative work in massage parlours, and health and beauty spas are strategically placed on bus benches outside factories. Immigration officials also reinforce these narratives, as illustrated by a spokesperson from the Immigration Department quoted in the newspaper:

[A] quick call and a visit to the nearest 'traditional massage parlour', any time of the day, is all customers need to do to satisfy their sexual lust. This tactic has recently surfaced in Johor Baru, where a group of foreign women are offering their special services…. It is learnt that most of the illegal activities take place at premises that use traditional massage parlours and reflexology centres as fronts.[30]

-

Yet in some cases it is the migrant workers themselves who are subjected to sexual harassment—but only the most sensational accounts reach the newspapers. When a Bangladeshi factory supervisor forced a number of Cambodian women to have sex with him it made the headlines, but for cases of sexual harassment in general the reports are limited.[31] This focus blurs the fact that management uses ethnic and gender divisions on the factory floor to create hierarchies of power where women are left in vulnerable situations. It also frames male workers as sexual deviants who commit crimes against vulnerable migrant women in order to satisfy their sexual urges. While there have been a number of cases where migrant women have been raped and robbed by migrant men, these cases are the exception rather than the rule, and they are less common than Malaysian citizens perpetrating crimes against other Malaysian citizens.[32] Moreover, migrant women are often professed to be victims of traffickers and smugglers, and in some cases they are, but there are many women who choose to migrate to get work.

Unruly men and invisible women: acts of resistance and regulation

-

As in the early industrialisation period, newspaper reports strengthen and shape discourses of migrant workers in the manufacturing industries. Young Malay women living away from family posed a threat to the social fabric of Malay society back in the 1970s whereas male migrants of today are viewed as troublemakers who disrupt national stability, and female workers are the impetus of male violence. This is exemplified in the New Straits Times (NST) report, which cited a female foreign worker as the cause of a fight between large groups of male foreign workers in a textile factory in Nilai:

More than 200 foreign workers from Vietnam and Bangladesh rioted and clashed outside their hostels at a textile factory…. Leaving 23 of them injured and three hospitalized…. Deputy state police chief…said the incident happened when a Bangladeshi worker tried to get friendly with a Vietnamese woman while working the night shift on Monday. However, the woman did not entertain the Bangladeshi man and later complained to her boyfriend, a Vietnamese, who also worked in the factory. Her boyfriend who was upset over the incident later brought several of his friends to beat up the Bangladeshi man, causing tension between the two groups.[33]

On the government website 'Doing Business in Malaysia' the government promotes a stable workforce to attract foreign investment. In this case, worker resistance is viewed as deviant behaviour because it disrupts images of worker stability. These outbursts of uncontrollable masculine violence threaten economic production and enable employers to 'control' and discipline workers via the police and immigration department. But disciplinary power only re-produces outbursts of resistance, as exemplified by three similar incidents which occurred at the same factory over a number of years:

The factory will be temporarily closed…. Yesterday's incident is the third such riot at the hostel, with the first one occurring on Jan 17, 2002, where about 500 Indonesians rioted and destroyed police vehicles after one of their friends was detained by police for drug abuse. On Sept 22, 2003, a group of Indonesian and Vietnamese workers fought after an Indonesian was chased and hit by a drunken group of Vietnamese. Six Indonesian workers were injured in the incident.[34]

-

These outbursts, like the earlier hysterical outbursts in the manufacturing factories, can be viewed as resistance strategies against capitalist discipline and immigration policies. However, local newspaper reports reproduce gendered discourses of hyper-masculinity and docile women, thus deflecting attention away from the real problems that foreign workers experience in the factories. These reports also inflame Malaysians' animosity towards migrant workers, evident in a survey conducted near an area where migrant workers meet their friends and shop on their day off. One Malaysian asserted, 'I fear fights may break out and that Malaysians may get hurt.'[35] And another said, 'I hope the police will place their men at all the places where these migrant workers congregate to exert some control over them.'[36] Many migrant workers interviewed felt Malaysians looked down on them. In the survey there is certainly evidence to suggest that Malaysians have strong feelings when it comes to migrant workers. As another Malaysian asserted, 'During public holidays and weekends parts of city centres and towns are swamped with foreign workers in their flashy outfits; they are quite loud, vociferous and scary.'[37] Another said, in a newspaper article, 'Hopefully, the government will review its policy on issuing work permits to foreigners, and locals should take up the jobs usually undertaken by foreigners.'[38]

-

On the positive side, lawyers, NGOs and trade unions provide support for migrants in Malaysia. They pressure the government for a rights-based migration policy to replace the managed migration policy which indicates a change from language of development to a more humane perspective on migration. Since the Bar Council held a conference on developing a comprehensive policy framework for migrant labour which was attended by representatives for the International Labour Organisation (ILO), advocates have continued to pressure the government over abusive conditions to which migrant workers are subjected. The biggest problems for migrant workers appears to be outsourcing companies, exorbitant recruitment costs, poor wages, limited health benefits and security.

-

Religious groups also provide community, education and social networks for male and female migrant workers across Malaysia. Christian outreach organisations provide assistance to those who need help dealing with the embassies, immigration department, the police and the Ikan Relawan Rakyat Malaysia (RELA) teams.[39] There are times when workers leave their employers, in which cases their work permits are cancelled and they are termed 'illegal.' These workers are in danger of abuse but, simultaneously, have more freedom to move around. Religious organisations unintentionally also reproduce dominant discourses of migrant workers as a problem. This is exemplified in the following quote from a Christian outreach spokesperson:

Foreign workers here are also besieged by social problems such as, unwanted pregnancies, sexually transmitted diseases, alcoholism, in-fighting, robbery and gambling. Many do not know whom to turn to for help due to the language barrier (many are not fluent in the local language or English). Our ministry works closely with them, offering them legal support, teaching them about the dangers of HIV/AIDS and starting them on English language classes. Most importantly, we offer them spiritual guidance through learning and sharing from the Bible and ultimately, hope to welcome them into our church.[40]

-

These organisations attempt to address anti-social behaviour and provide important functions beyond religion and advocacy to assist in the discipline of both male and female migrant women. During fieldwork it was noticed that the Catholic, Methodist and Presbyterian churches sponsored pastors from migrant host countries to target specific ethnic groups such as the Vietnamese and Nepalese. Religious clergy who share the same language and culture as the migrant worker are likely to have more success than Malaysians at addressing the social issues mentioned above. Migrant workers who attend church services and bible studies are perceived to be rendered more 'docile' because the ethnic grouping provides the workers with a sense of community, diverting attention away from the heterogeneities among overseas migrants and the social isolation they experience. This focus on migrant workers and religious pacification is reminiscent of the early industrial period when Japanese factory management provided prayer rooms in the factories to assist in the management of Malay workers.

Malaysia's new focus: non-labour-dependent, high-productivity outcomes

-

In the most recent national debates concerning Malaysia's economic growth and the recruitment of migrant workers old and new, competing and contradictory discourses are played out. Migrant workers are needed but not wanted. Migrant workers undermine economic growth. Migrant workers are not needed and not wanted. The major stakeholders from within and outside the government have had different views on development and the use of cheap labour from neighbouring countries. But different stakeholders now view migrant labour as an impediment to Vision 2020.[41]

-

For over a decade now, the MTUC has been pressuring the government to stop the flow of foreign labour on the grounds that it depresses the wage structure and weakens incentives to attract Malaysian workers, but the Human Resource Ministry has ignored the calls to stop the importation of cheap 'docile' labour in favour of capitalist demands. In the most recent debates surrounding migrant workers the government has turned full circle agreeing the long term employment of foreign labour has dampened wage growth and higher technology development. According to the Human Resource Minister Subramaniam, a 2009 study revealed (as quoted by a journalist) the following:

Thirty-four per cent of the estimated 1.3 million [foreign] workers in the country earn less than RM700 a month This figure was below the poverty line of RM720 per month. He said the National Employment Return study had stressed that wages needed to be increased because the country's wage trend only recorded a 2.6 per cent growth annually over the past 10 years compared with the increasing cost of living during the same period. Subramaniam said the influx of foreign workers was among several reasons why wages had not increased for the past 10 years. He said that 'Skilled jobs are synonymous with higher wages'. However, in many instances, employers do not pay for skills instead they rely on unskilled foreign workers. This has largely dampened wage growth.[42]

Providing cheap docile labour to global capital comes at a cost to both workers and the nation. The following quote from another government official reflects the dilemma the nation state faces:

The foreign based electrical and electronics firms have declared, in their dialogue sessions with the government, that they would be forced to move out if foreign workers were to be limited or stopped! This argument, if accepted will mean that our economy could remain in the middle income trap for the foreseeable future.[43]

-

The government's economic plan anticipates fewer migrants, but employers complain they could not produce without migrant workers. In July 2011 the government stopped the entry of new migrant workers in the hope of legalising some of the large number of undocumented migrant workers already in the country through an amnesty.[44] Amnesty in this context is the moving of migrant workers who are already contributing to the economy from 'illegal' to 'legal' status. This means that the government sees these workers as performing paid work that Malaysians no longer want. At the same time, once migrant workers are 'legal,' the employers must pay the levy to hire migrant workers so the government gets an additional bonus.

-

According to a business study, the government at some point must take the foreign worker issue seriously:

With the government's renewed goal to be an advanced industrialized nation through the launch of the New Economic Model, foreign worker issues now have to be addressed comprehensively and strategically. As Malaysia can no longer afford to accommodate labour-intensive industries, the focus now is to scale down the unskilled foreign worker population. It will, however, have to be done on a gradual basis so as not to hurt employers and company operations. That is why under the 10th Malaysia Plan (10MP, 2011–2015) the government has proposed a multi-tiered levy system.[45]

In this quote, the workers' interests are invisible. The new system aims to regulate the entry of foreign workers by offering companies incentives to eventually put in place non-labour-dependent, high-productivity processes. The outcome remains to be seen.

Conclusion

-

I have shown the historical connections between Malay female factory workers in the 1970s and 80s and migrant women's labour in Malaysia today. In the 1970s and 80s scholars highlighted the struggles female workers endured during the early period of modern industrialisation. Many workers were upset and confused because their good work was forgotten amidst the sensational newspaper narratives of the time. In protest, Malay women staged hysterical outbursts over the harsh factory discipline and caused disruptions to production. Alarmed over the hysterical outbursts, more nuanced forms of discipline, such as the provision of prayer rooms and counselling services, were established. In recent times, Christian outreach initiatives provide advocacy and education services for migrant workers and contribute to migrant worker discipline through the teachings of the Bible.

-

Although there is an overlap in the discourses of women and work in the early and most recent period, female migrant workers, unlike Malay workers, are considered victims of male workers, recruiters and employers, or as women whose productive and reproductive roles must be separated so they contribute to the economy but not to the Malaysian population. Migrant workers have to survive in Malaysia within a tortuous array of discourses which highlight the victimisation and sexuality of migrant women and the rampant masculinity of migrant men.

-

Foreign workers in today's export manufacturing industries have also become the subject of a separate discourse that is not analogous to Malay workers in the early industrial period. Factory work is devalued because migrant workers carry out the work and because the industries they work in are considered sunset industries. As the nation progresses to a higher stage of development, the value of these workers and the light manufacturing industries they work in becomes invisible. Nevertheless, according to national narratives in both periods working class bodies must be disciplined, lest they may chase investors away.

-

The myth of the docile and passive female worker in the stable workforce continues to be reproduced in development discourses but the hysterical outbursts and migrant riots tell a different story. For migrant workers the harsh factory discipline, ethnicity stratification, and strict immigration policies have caused riotous outbursts among different ethnic groups leading to denigration by Malaysian society, and further discipline and surveillance. Migrant issues are heatedly discussed between different groups, and many unionists, NGO groups and Bar Council lawyers argue in favour of the rights of migrant workers against an often hostile community.

Notes

[1] In 2008 labour costs in Malaysia were around US$1.18 per hour whereas labour costs in Vietnam were around US$0.38 per hour. Malaysian Knitting Manufacturers Association, 'Statistics,' 2000, online: http://mfg.asiaep.com/ass/mkma/stat.htm, site accessed 31 May 2009.

[2] Dong Sook Gills and Nicola Piper (eds), Women and Work in Globalising Asia, London: Routledge, 2000.

[3] David Harvey, Spaces of Global Capitalism: Towards a Theory of Uneven Geographical Development, London: Verso, 2006.

[4] 'Southeast Asia,' Migration News, vol. 16, no. 4 (2009), online: http://migration.ucdavis.edu/mn/more.php?id=3558_0_3_0, site accessed 29 January 2010.

[5] Vicki Crinis, 'Sweat or no sweat: foreign workers in the garment industry in Malaysia,' Journal of Contemporary Asia, vol. 40, no. 4 (2010): 589–611.

[6] In the factories in this study the bulk of workers in the clothing industry were female but there were also factories with large numbers of male workers. In the textile industry male workers formed the largest number of workers and in electronic and foodstuffs industries workers were divided between male and female.

[7] The research is part of a project funded by the Australian Research Council (ARC), a collaborative research study of the clothing industry and its workers in the Asia Pacific post-2005.

[8] Aiwha Ong, Spirits of Resistance and Capitalist Discipline, Factory Women in Malaysia, Albany: State University of New York Press, 1987; Michel Foucault, The History of Sexuality Volume I: The Will to Knowledge, London: Penguin London, 1988.

[9] The colonial government left Malaya reliant on exports such as tin and rubber. Since the NEP (the Second Malaysia Plan) the country has focused on developing its export industries—electronics, garment and textiles. This also includes resource-based industries involving older and newer primary products such as palm oil and non-resource-based industries. During the early 1970s palm oil exports topped the record but export manufacturing was promoted as the industrial policy which would bring Malaysia's development aspirations to fruition. 'Malay Mail Feature: Hari Kebangsaan Malaysia,' Malay Mail, 31 August 1970. Since the 1970s, non-resource-based industries have been the most successful, particularly the electronic industries.

[10] Aihwa Ong, 'State versus Islam: Malay families, women's bodies, and the body politic in Malaysia,' in Bewitching Women and Pious Men, ed. Aihwa Ong and Michael Peletz, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995, pp. 159–94.

[11] Alison Wee Sui Hui, Assembling Gender: The Making of the Malay Female Labour, Selangor: Strategic Info Research Development, 1997.

[12] Ong, Spirits of Resistance and Capitalist Discipline, Factory Women in Malaysia.

[13] Ong, Spirits of Resistance and Capitalist Discipline, Factory Women in Malaysia.

[14] Aihwa Ong, 'Japanese factories, Malay workers class and sexual metaphors in West Malaysia,' in Power and Difference, ed. Jane Monnig Atkinson and Shelly Errington, Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1990, pp. 385–422.

[15] Raymond Lee's study of factory workers in Malacca noted that 'more than 40 outbursts of mass hysteria occurred among the Malay female workers between July 1977 and 1979,' See Raymond Lee, 'Hysteria among factory workers,' in Malaysian Women: Problems and Issues, ed. E Hong, Penang: CAP, 1983, pp. 76–80.

[16] Jamilah Ariffin, Women and Development in Malaysia, Petaling Jaya, Kuala Lumpur: Pelanduk Publications, 1992.

[17] Ong, Spirits of Resistance and Capitalist Discipline, Factory Women in Malaysia.

[18] Ong, 'Japanese factories.'

[19] Jomo K.S. (ed.), Malaysian Eclipse: Economic Crisis and Recovery, London: Zed Books, 2001.

[20] Maznah Mohamad, 'The management of technology, and women, in two electronic firms in Malaysia,' in Positioning Women in Malaysia, ed. Cecilia Ng, London: MacMillan Press, 1999, pp. 95–166.

[21] Ishak Shari, 'Economic growth and income inequality in Malaysia, 1971–95,' Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy, vol. 5, nos 1 & 2 (2000): 125–40.

[22] 'Semi-skilled female workers who have been retrenched face the burden of learning new skills,' New Straits Times, 8 January 2002.

[23] Rajah Rasiah, 'Expansion and slowdown in Southeast Asian electronics manufacturing,' Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy, vol. 14, no. 2 (2009): 123–37; Vicki Crinis, 'Global commodity chains in crisis: the garment industry in Malaysia, the before, the now and the hereafter,' Institutions and Economies, vol. 4, no. 3 (2013): 61–81.

[24] 'Robbers preying on "timid" foreign workers,' New Straits Times, 31 January 2009.

[25] 'Southeast Asia,' Migration News.

[26] Vicki Crinis, 'Vietnamese migrant clothing workers in Malaysia: global production transnational labour migration and social reproduction,' in The Global Political Economy of the Household in Asia, ed. Juanita Elias and Samanthi Gunawardana, Hampshire: Macmillan, 2013, pp 162–67.

[27] Personal Communication with Female Migrant Workers, Batu Pahat, Johor, Malaysia, August 2009.

[28] Hariati Azizan Ann Tan and Sylvia Looi, 'Marrying for money,' the Star (Kuala Lumpur), 20 February 2011.

[29] 'Rm900 fine for prostitution,' New Straits Times, 20 August 2009.

[30] Ben Tan, 'Ten foreign sex workers arrested in raid,' New Straits Times (Kuala Lumpur), 24 June 2010.

[31] 'Factory supervisor forced us to have sex,' New Straits Times, 25 June 2011.

[32] 'Robbery rape gang busted,' New Straits Times, 8 February 2008; 'Gang rape ordeal for two Vietnamese workers also robbed by their rapists,' New Straits Times, 18 September 2007.

[33] Patrick Sennyah, 'Workers clash over a woman,' New Straits Times (Kuala Lumpur), 9 June 2011.

[34] Patrick Sennyah, 'Workers clash over a woman.'

[35] Halim Said, 'Migrant workers in full Force in KL city centre,' New Straits Times (Kuala Lumpur), 2 February 2011, p. 2.

[36] Halim Said, 'Migrant workers in full Force in KL city centre,' New Straits Times (Kuala Lumpur), 2 February 2011, p. 2.

[37] Said, 'Migrant workers in full Force in KL city centre,' p. 2.

[38] Halim Said, 'Migrant workers in full force at KL city centre,' New Straits Times, 2 February 2011.

[39] The people's volunteer corps (Ikan Relawan Rakyat Malaysia) known as RELA.

[40] Personal Communication with Spokesperson for Tenaganita, Penang, 2009.

[41] Vision 2020 is a Government Development trajectory to reach a fully developed nation by the year 2020 set out in 5 year Economic Plans.

[42] Halim Said, 'Influx of foreign workers dampens wage growth,' New Straits Times (Kuala Lumpur), 5 August 2010.

[43] Fong Chan Onn, 'Caught in middle-income trap,' Star (Kuala Lumpur), 7 February 2010.

[44] '1.9m foreign workers, illegals registered under 6p programme,' New Straits Times, 15 August 2011.

[45] Hamisah Hamid, 'A laborious issue,' New Straits Times (Kuala Lumpur), 5 May 2010

|