Gender and the Consort Queen in Tonga

Areti Metuamate

-

To understand the kingship system of Tonga one must also understand the place of the consort queen as essential to the functioning of the system. Since the Tupou dynasty officially commenced in 1845,[1] Tonga has had five kings and one queen regnant, with all the monarchs, except for King George Tupou V, having a consort. While the Tongan process of royal marriage focuses on the need for building alliances between aristocratic (noble) families, and places great importance on the fertility of suitors to royal princes (and princesses), there are important informal roles played by those who marry into the royal family; roles that shape and influence the place of the monarchy just as much as the formal, constitutional, and ceremonial elements performed by the monarch that are so widely seen and documented (such as the opening of Parliament, the assenting of laws, and officially appointing the elected Prime Minister).

-

In this paper, I consider the significance of the consort to the Tongan monarch by exploring the position of the current queen consort to King Tupou VI, Queen Nanasipauʻu. By understanding her unique positionality, one is better able to understand the often underrated role the queen consort plays in ensuring the very survival of the Tongan kingship system. I will consider questions around what qualifies someone to marry a King, what being the wife of a King means in practice, how the queen consort ranks in relation to other members of the royal family (including how this varies in different contexts), and finally, what Tongans see as the role of the queen consort (and of a King without one).

Nanasipau'u Vaea

-

The Queen consort, Nanasipau'u Tuku'aho (nee Vaea), was born on 8 March 1954, the eldest child and daughter of nobleman Baron Vaea (who became a widely respected and popular Tongan prime minister later in his life),[2] and his wife Baroness Tuputupu Vaea (nee Ma'afu). In the sentence above, I have deliberately highlighted a distinction between being the eldest child and being a daughter, to note the significance of the rank of female members of a family which will be explored further below to outline how personal (blood) ranking works practically, or at least how it is meant to work practically, within the ranks of the Tongan aristocracy.

-

As the eldest son in a primogeniture system, Nanasipau'u's younger brother 'Alipate Tu'ivanuavou succeeded to his father's noble title, Vaea,[3] when the Baron died in June of 2009 at the age of eighty-eight years.[4] While Lord Vaea's title makes him the head of his kāinga, or group of relatives under a chief, his sister outranks him within the family (and outside the family too, due to her status as Queen), because as the eldest daughter her personal or blood rank[5] is higher than that of any of her siblings, especially her brothers. This particularly gives Nanasipau'u a superior status over their children, especially the children of her brother, in line with the Tongan family ranking of sisters being higher than brothers and the eldest sister having the highest status. In the Tongan 'api or household and wider kāinga kinship, everyone is ranked in relation to others. The 'relative 'eiki-tu'a statuses were determined by … fundamental rules of kinship. Sisters (tuofefine) were invariably 'eiki to their brothers'.[6] Andy Mills determines that these hierarchical principles created relational tapu.

Those who were relatively 'eiki within the household were relationally tapu to those who were tu'a in relation to them. Thus, male (tuonga'ane) and female (tuofefine) siblings had a strong avoidance relationship because sisters were tapu to brothers … The father's sister (mehikitanga), as well as having particular rights and privileges in relation to her brother's children, was tapu to them … the mother's brother (tuasina) was the focus of the fahu relationship … The grandfather (kui tangata) was … free to interact with his grandchildren … these double-articulated relationships illustrate the parallel redoubling and cancelling-out of tapu or ngofua statuses.[7]

-

Even before her marriage to a royal prince, Nanasipau'u's noble heritage positioned her as a senior woman in the Tongan nobility. The late Baron Vaea was the son of Vīlai Tupou (half-brother to Queen Sālote Tupou III) and a senior noblewoman, Tupou Seini. Baron Vaea's wife, Tuputupu, was the daughter of the Noble Ma'afu. By a number of bloodlines, Nanasipau'u is a cousin to her husband, King Tupou VI, a common feature of marriages throughout noble and royal families across the world. This is especially pronounced for Tongans, given the relatively small population (just over 100,000 people living in Tonga and around the same number living in the diaspora), and the even smaller subpopulation of the Tongan nobility, which even at its broadest interpretation (that is, including the children and grandchildren of nobles, is estimated to be less than 1,000 people).[8]

Being of the right birth

-

In Tonga, being of the right birth to marry into the royal family usually means being related to them at some level. Commoners are not seen as eligible to marry a member of the royal family.[9] In the case of the current King and Queen, there are at least three ways they are related. Perhaps the most prominent connection is through their mutual ancestor, King Tupou II.

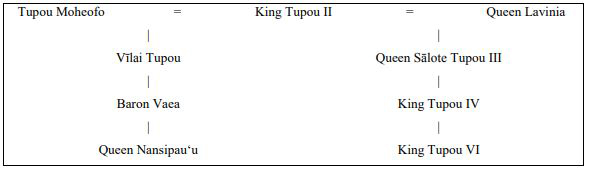

Table 1. Queen Nanasipau'u and King Tupou VI both descend from Tupou II

Source. Manutu'ufanga Naufahu, July 2015.

-

When Tupou II married his first wife, Queen Lavinia (with whom he later had a child, Sālote), he already had a son named Vīlai Tupou, to the senior chieftainess Tupou Moheofo. To this son, Nanasipau'u's father, Siaosi 'Alipate Tupou (later Baron Vaea), was born. While Vīlai Tupou was not a legitimate son of Tupou II, he was privately and publicly accepted by Queen Sālote as her half-brother, giving him a special status befitting of the rank of his father and of his mother. In this line, Nanasipau'u's father was a first cousin by blood to King Tāufa'āhau Tupou IV, the father of King Tupou VI (See Table 1).[10]

-

Through another line, where Tupou Moheofo later married Siale 'Ataongo, there is a connection between Queen Nanasipau'u and King Tupou VI via the King's mother, Queen Halaevalu Mata'aho. Queen Halaevalu Mata'aho's mother, Heuifanga, was first cousin to Baron Vaea (Queen Nanasipau'u's father) on his father's side (See Table 2).[11]

Table 2. King Tupou VI's maternal great-grandmother was Queen Nanasipau'u's grandfather's sister

Source. Manutu'ufanga Naufahu, July 2015.

-

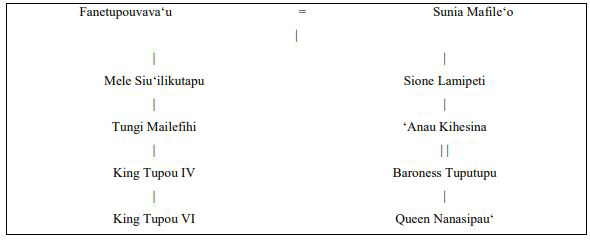

Through her mother, Baroness Tuputupu, Queen Nanasipau'u is again related to King Tupou VI. Tuputupu is the granddaughter of Sione Lamipeti, who is brother of Mele Siu'ilikutapu, the King's great-grandmother on his father's side (See Table 3).[12]

Table 3. King Tupou VI and Queen Nanasipau'u both descend from Fanetupouvava'u and Sunia Mafile'o

Source. Manutu'ufanga Naufahu, July 2015

-

These relationships are close enough, but not too close,[13] to ensure a well-suited marriage was possible between people of the right birth rank. In Tonga it is unheard of for a King to be married to anyone other than the daughter of a senior nobleman or noblewoman. As Manutu'ufanga Naufahu told me:

And though Queen Nanasi [Nanasipau'u] was not necessarily the highest ranked woman of her generation, she was very senior in the Tongan nobility which meant if she was to marry a prince, she would be able to hold her own as a princess or even as the queen, as she eventually went on to become, because she was of the right birth rank. She was also polo'i, meaning she was specifically chosen or appointed [by the King] to be a royal wife.[14]

-

Queen Nanasipau'u's marriage to King Tupou VI was not unusual in terms of their close kinship ties, and neither was it unusual that a Noble's daughter would marry the King's son as 'the ideal in the past has been for noble heirs [and their eldest daughters] to marry 'up', preferably within the kindreds of the king and [higher ranked] nobles, or at least to intermarry with the immediate families of other titleholders'.[15] It was explained to me that in a sense Nanasipau'u did not really have a choice on who she married. Because of her status,

her husband was always going to be chosen by the King as that is part of the Tongan culture. King Tupou IV and Queen Mata'aho chose her to marry their youngest son and she accepted. That is a sign of someone who is obedient, humble and loyal. Talangofua, anga fakatokilalo and tali angi are the three Tongan words for that.[15a]

-

As explained to me by a woman I was seated near at the wedding reception of the current Crown Prince and Crown Princess, on 12 July 2012, Tongans are very clear about whether a person is ranked appropriately to marry a member of the royal family, and they do not condone people marrying above their rank without the appropriate pedigree of their own. The generally accepted view in Tonga is that commoners marry commoners, nobles marry nobles, except in some cases where senior nobles marry royals. But the reality on the ground is quite different as many nobles and children of nobles have married commoners. It was explained to me by one interlocutor that despite a sense of greater tolerance about this today, many Tongans still believe that it should be the case that people marry at their own rank level, or slightly above in the case of someone marrying into the royal family.[16]

The rank of the Queen consort

-

Rank and status in Tonga, and how one abides, or not, by the accepted customs and protocols, are fundamentally linked to the broader patterns of contemporary Tongan sociality. Much of what dictates Tonga's hierarchy is based on knowing your genealogy and how your rank positions you in relation to other people, both within your family and outside it. This, Helen Lee explains, determines your status because rank is a 'fixed social category, and status, [a] contextual social position'.[17] The distinction between the two is subtle, but important. 'Rank is fixed at birth, and the most fundamental distinction made in the ranking system is that between 'eiki (chief) and t'ua (commoner)'[18] while 'status is calculated in context and is relative: that is, in any given context, a person's status is relative to that of whoever else is present.'[19] In Tonga, both one's rank and one's status is palpably very important.[20] As Elizabeth Wood-Ellem wrote:

'Rank is everything,' said Queen Sālote, but rank is sometimes absolute (personal or blood rank) and sometimes relative (kainga rank or rank by title). Personal or blood rank is based on the sum total of the rank of one's ancestors … Relative or kainga rank applies on ceremonial occasions, such as funerals, where relationships through a certain person (the corpse in the case of a funeral) determines whether one is 'high' ('eiki) or 'low' (tu'a) on that occasion. A person whose absolute rank was high might not eat at a feast if she or he is 'low' on that occasion; for example, 'low' is descended from the grandfather while 'high' is descended from that grandfather's sister. (Sisters always outrank brothers).[21]

-

In the usual context of official ranking,[22] the Queen consort is the most senior member of the royal family after the King. That is, in an 'order of precedence'[23] she is second, followed by any living dowager Queen (who in Tonga, as in the United Kingdom, is referred to as the 'Queen Mother'), the King's children, and then, the King's grandchildren. This order of precedence, which is applied in many monarchies across the world, acknowledges the official rank of a particular person relative to the monarch, and its variances in specific contexts. This ranking should not be confused with the Line of Succession, which is the official list of those who are next in line to succeed to the throne under the Tongan Constitution.[24]

-

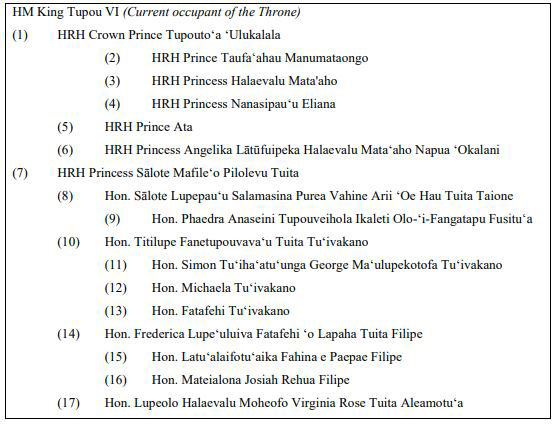

In Tonga, the Line of Succession is usually recorded and updated on the birth and death of key members of the royal family (see Table 4). An official order of precedence, however, is not recorded. At the time of publishing this article, I was unable to get confirmation from the Tongan Government as to whether the newest members added to Table 4 are, in fact, officially in the Line of Succession. I have, however, included their names on the assumption that they are.

Table 4. Line of Succession to the throne of the Kingdom of Tonga

Source. Initially accessed via the Tonga Ministry of Communications website, but the information is no longer published online. I have kept this list updated with personal knowledge of new births as they happened.

-

As with other Pacific Island hierarchies, such as Fiji, where, Christina Toren explains, there are two main hierarchical statuses, 'I cake' (honoured) and 'I ra' (less-honoured) which structure life and relations in Fiji. Tongan people arrange themselves around their status and that of others, whereby ideas of seniority, rank and gender combine. This is described by Toren as beginning in childhood for Fijian children, and she outlines that children learn about status and Fijian social hierarchy from an early age and order themselves accordingly, for example within the seating arrangements in school classrooms.[25] Within the traditional Tongan hierarchy, the ranking or status of a particular person can change depending on the context, and the example of the current Queen is used below to explain how this works in practice today.

-

As outlined, Queen Nanasipau'u, while second in the usual order of precedence, is not ranked as such in all contexts. This is because she has a lower personal blood rank than some other individuals in Tonga, and she is not the daughter of a royal prince. Thus there are some contexts where she is tu'a, for example to her sister-in-law, King Tupou VI's eldest and only sister Princess Sālote Mafile'o Pilolevu Tuita. The latter example is not entirely unique to Tonga. In the official order of precedence of the United Kingdom,[26] Queen Elizabeth stipulated that the Duchess of Cambridge (otherwise known as Kate Middleton) is expected to curtsy to the younger cousins of her husband, according to their rank as blood princes and princesses.[27] The exception to this rule, however, is when she is in the company of her husband, the Duke of Cambridge, Prince William, in which case his cousins must curtsy (if a woman) and bow (if a man) to her and her husband, recognising her rank as the wife of a future King. When Prince William does become King, and his wife queen, she will automatically become the second highest ranked member of the family even though she is not a blood princess.[28] But this relatively simple acknowledgement of the blood (birth) rank of a prince or princess is not nearly as complex as the system in Tonga.

-

Tonga's social ranking system goes far deeper than how 'royal' one's blood is, and, in fact, applies to the personal rank of each and every Tongan (not just those of noble or royal birth), including those in the diaspora (although it would be fair to say there is a growing disconnect between some Tongans living overseas, especially amongst those who were born overseas). As previously stated, Elizabeth Wood-Ellem describes the measure of a person's personal or blood rank being based on the 'sum total of the rank of one's ancestors',[29] and both Helen Lee and Adrienne Kaeppler argue that Tonga's hierarchical ranking system is 'the most pervasive concept in Tongan culture',[30] one which plays a 'crucial … [component] in the construction of individuals' sense of self'.[31]

-

An example of this construct is that a daughter born to a prince and a commoner woman would have a much lower personal rank than a daughter born to a prince and a noblewoman, even if the latter prince was the younger, more junior, brother of the former. Things become more complex when, for example, two noblemen each marry noblewomen and have children (who obviously have noble rank). To an outsider, the children of both sets of nobles may be viewed as equally 'noble' but in Tonga that is never the case.[32] There is always, in every context, someone who is 'eiki (superior in status) and someone who is tu'a (inferior).[33] Therefore, in the case of these two pairs of nobles, it is almost certain that one of them will have a higher combined rank, because of an ancestor (or ancestors) being of higher rank than the ancestor/s of the other pair. This would result in the children of the former pair ranking higher than the children of the latter pair. This way of determining rank would not be easily maintained in mainstream Australia or Aotearoa New Zealand, where the average person is not likely to know their ancestry beyond their own grandparents or great-grandparents. But in Tonga, people know a great deal about their ancestry, and many of those I interviewed easily recited the names of their ancestors, three, four and five generations back.

-

In July 2012, while visiting a small village in the north eastern part of Tonga's main island, Tongatapu, I came across an elderly woman selling coconuts who was kind enough to share with me some of her village's history. As we sat in the warm sun talking, her husband came to say he was going to Nuku'alofa, to which his wife responded she would stay with 'the Māori man to teach him some Tongan history'. This woman, whose name I am ashamed to admit I did not learn during this encounter, spoke about her family and how they had been caring for the land for many generations. She asked about my own Māori and Cook Island whakapapa/akapapa[34] and then, proceeded to tell me how her ancestor was related to the first Tongan King by reciting, from memory, the names of each ancestor from her mother, through to (what I recall being) her great-great-great-grandmother. I said to her that even as someone who has learnt parts of my own whakapapa, it was impressive that she could name five generations of her ancestors simply from memory, to which she replied she could go back even further on her father's side, and she could also recite the same for her husband's mother's and father's lines too. This depth of genealogical knowledge was commonly held by older Tongans I spoke to, both formally in interviews, and casually, in situations such as this, during my several field work visits to Tonga.

-

There was a consensus among those I interviewed that it was simply 'known' who ranked higher than others, depending on the context, and that this 'did not need to be written down'.[35] Even so, in my observations and conversations in Tonga and amongst the Tongan diaspora, while people clearly understood who ranked higher than who in general society (and while everyone accepted that nobles ranked higher than commoners and royals ranked higher than nobles), it appears that the subtleties of the ranking of members of the royal family relative to each other were not as clearly known or understood by everybody.

-

Unlike the monarchies of the United Kingdom and Thailand, the context within which any order of precedence operates appears to change frequently in the Tongan Kingdom, depending on the specific occasion, and which members of the royal family are present on each occasion. In my observations at a number of events in Tonga and in the diaspora I noted what seemed to be subtle changes in the ranking system. For example, at an official parliamentary/government-sponsored event, the order of precedence appeared to look like this:

1. The King

2. The Queen

3. The Queen Mother

4. The King's children

5. The King's grandchildren

6. The King's sister

7. The King's sister's children

8. The King's sister's grandchildren

9. The King's brother's children

10. The Prime Minister

11. The Speaker

12. Nobles

But in many other ceremonial events in the community, and in the villages, or even those hosted by the royal family, the order of precedence usually looks like this:

1. The King

2. The Queen

3. The Queen Mother

4. The King's sister

5. The King's children

6. The King's grandchildren

7. The King's first cousins

8. The King's brother (Ma'atu's) eldest son

9. The King's sister's children

10. The King's brother (Ma'atu's) other children

11. The King's sister's grandchildren

12. Nobles

-

Ana[36] explained that the order could be different in some ceremonial contexts where, for example, the King's sister's status is elevated by her blood rank (as the daughter and sister of kings).[37]

1. The King

2. The Queen Mother

3. The King's sister

4. The Queen

5. The King's children

6. The King's grandchildren

7. The King's sister's children

8. The King's brother's children

9. Nobles

- Going one step further, in a more strict interpretation of the appropriate Tongan context, recognising the personal blood rank of all individuals results in another different ranking order (changed according to context). In such a context, the general ranking order would look like this:

1. The King

2. The Queen Mother

3. The King's sister

4. The King's sister's children

5. The Queen

6. The King's children

7. The King's grandchildren

8. The King's paternal first cousins

10. The King's sister's grandchildren

-

Figures 1 and 2 show Queen Nanasipau'u, then as Crown Princess, seated on the ground at the funeral of her mehikitanga, Vaohoi Naufahu, while at the same time her mother-in-law, the Queen Mother, and her niece by marriage, Lupepau'u Tuita, were seated on chairs in a prominently situated marquee/shelter. The then Crown Princess chose to acknowledge her liongi status, that is a status of being lowly in relation to the deceased, rather than be seated with her mother-in-law and niece where she could rightfully have sat as a senior member of the royal family. Manutu'ufanga Naufahu explained to me that the then Crown Princess was demonstrating her personal commitment to respecting her mehikitanga in line with anga fakatonga.[38]

Figure 1. The then Crown Princess Nanaipau'u seated on ground at funeral of her aunt Vaohoi

Source. Manutu'ufanga Naufahu Facebook. Used with permission.

Figure 2. The Queen Mother (Nanasipau'u's mother-in-law), and Hon Lupepau'u Tuita (Nanasipau'u's niece by marriage) seated at the funeral of Vaohoi

Source. Manutu'ufanga Naufahu, Facebook. Used with permission.

-

Noting the higher blood rank of women within the family, this is what the personal blood rank of the royal family would look like, if ranked strictly in accordance with personal blood rank:*

1. The King's sister (although it was argued that the King's eldest female paternal first cousin ranks either alongside or directly below his sister)

2. The King's sister's eldest daughter **

3. The King

4. The King's daughter

5. The King's sons

6. The King's grandchildren

7. The King's paternal first cousins (noting the point above about his eldest female paternal first cousin)

8. The King's brother's children

9. The King's sister's grandchildren

10. The Queen Mother

11. The Queen

* = In reality, this ranking system is only very infrequently given practical life, an example being after the death of the late King George Tupou V, when female members of his family had their hair cut as a public expression of their close but inferior relationship to the King, it was the King's only sister, and his eldest female first cousin on his father's side, who cut the hair.

** = In a strict hierarchical sense, the eldest daughter of the King's sister (who is his eldest sister) has superior personal blood rank to anyone other than her mother, and her eldest (and only) daughter has a superior personal blood rank to anyone other than her mother and grandmother (although on top of the female/male distinction, there is sometimes also a generational one). Indeed, there is no general rule for how many generations this ranking system would work, as it becomes hard to know as the generations go by with so many different intermarriages eventually crossover occurs.

-

The King's eldest and only sister, Princess Pilolevu, has no mehekitanga as her father had no sisters, and some people I spoke with said she in fact has no fahu given her father had no paternal aunt.[39] This anomaly in any typical Tongan family might mean the person without direct aunts/great aunts would then look to great-great aunts (and their descendants) to identify who their fahu is, but in the case of someone of such unparalleled high rank, that would seem futile because it is unlikely anyone so distant could act as fahu of someone in such a senior position.

-

As has been described, the fluidity of the ranking systems (particularly for the Queen consort and Queen mother given they are not holders of these positions because of their blood rank), means that in the current Royal Family, Queen Nanasipau'u does not always have the second highest rank (as would be the case for the consort to the British or Thai monarch, for example).[40] The fact that there is such diversity/contextual variation within the ranking system means that all those who are in the system are hyperalert and sensitive to the distinctions.[41]

Balancing kingship: Born to be queen

-

I have met Queen Nanasipau'u a number of times in Canberra, Auckland and Tonga over recent years, and interviewed her with the King for this paper at their home estate of Liukava, near Kolovai on Tongatapu. She is a softly spoken, gracious, somewhat shy, person who is widely seen as a conservative and traditionalist. Indeed, some people I interviewed suggested she was too focused on holding on to the old ways, while others believe she is simply doing what a good Queen should do by protecting the heritage of Tonga and its royal and noble families. It seems to me that the Queen is a powerful role model for maintaining the customs and practices of Tonga, and particularly in respect of royalty and nobility. She is also a devout Christian who is widely respected for her clear attempts to maintain the close links between the monarchy and the (Free Wesleyan) Church.

-

I have a particularly strong memory of Queen Nanasipau'u walking down the aisle of the Centenary Church in Saione, Nuku'alofa during the Coronation ceremony for her and her husband. It struck me as she walked slowly down the aisle with an expression of both humility and pride (if it is possible to express both at the same time) that she carried just as much history on her shoulders as did her husband, the King. Indeed, it occurred to me that her place in the entire process of kingship is integral to the survival of the monarchy in Tonga, not simply because of the fact that the King's children and grandchildren were only made possible through her,[42] but also, as I show through the insights of my interlocutors, because many Tongans see kingship as not entirely complete without a queen.

Figure 3. King Tupou VI and Queen Nanasipau'u at their Coronation ceremony, Nuku'alofa. July 2015

Source. Tonga Palace Office. Used with permission

-

Although I have undertaken research on the kingship of King George Tupou V over the past six years, one thing that I have not examined is the view held by some that a monarch without a consort was, in a sense, diminished. This is about more than simply seeing the role of the consort as a procreator of children, as important as that is, especially in the case of a monarchy. It is about understanding the important symbolic role the consort has, as companion to the monarch and in the practical roles, such as being present to open significant sites, presiding over family and national events, the consort ensures a balance in the duties and role of the monarch. Apart from the crucial role Queen Nanasipau'u has as mother to the King's children, she also brings a depth of experience as a Tongan woman, and someone raised in the upper echelons of the Tongan nobility. She also brings her own lineage, associated supporters (with reciprocal responsibilities), and is the one person who helps to carry the monarchy, as her husband's closest advisor and confidante.

Figure 4. King Tupou VI and Queen Nanasipau'u at the Thai King's funeral, Grand Palace, Bangkok, Thailand, October 2017

Source. Tonga Palace Office. Used with permission

-

As Queen Nanasipau'u walked down the aisle at her Coronation, I saw tears streaming down the face of one of her close relatives. Near this woman were her own children and other family members, all displaying the depth of emotion they clearly felt at seeing their close kin officially recognised in this historic ceremony. I happened to be walking out of the church with the same person after the ceremony, and while I was filming the masses of people on my phone, she asked me what I thought about the occasion. I said I was honoured to witness such a historical day. When I asked her what she thought, her response was heartfelt.

I was overcome with joy to be here to see our King and our Queen crowned. I could not stop the tears flowing. I don't know where they were coming from but they just came out. They would not stop.

'And what was it that really brought these tears out from you?' I asked.

I guess it was seeing the ***Queen, Nanasipau'u, and knowing that she has been there for the King and the Royal Family as the one to ensure the monarchy will go on into the future. I was so proud for her and for who she is and for her place in our history. But for sure it is the new King who carries Tonga now, but for sure it is the Queen who helps to bear the load. This is a very beautiful day for Tonga.[43]

-

In many ways Nansipau'u was elevated to the position of queen consort having had more preparation than anyone else for the role. At age sixty-one, Nanasipau'u was the eldest person to be crowned queen consort in the history of the Tongan monarchy, but quite the opposite of being too old, the queen was both ready and ripe for the role she was eminently qualified to undertake. No queen consort had ever had the life experience that she did when she was crowned. A Tongan friend of mine suggested that Nanasipau'u was always 'destined to be Queen one day',[44] noting the widely accepted view that she was one of the few eligible suitors to King George Tupou V when he was a younger prince.

There was an expectation that the Crown Prince [later King George Tupou V] would marry someone of appropriate high ranking, and of course Nanasipau'u was one of the few. There were probably only two or three but he did not want to marry any of them, instead refraining from marriage leaving them to find others of lesser rank to marry. But Nanasipau'u was raised well and she was not going to marry just any noble and in the end she got the prize. She married the youngest son of King Tāufa'āhau Tupou IV and Queen Halaevalu Mata'aho and not only was he good looking, but he was next in line shortly after they married because his other brother was stripped of his royal inheritance for marrying a commoner.[45]

-

My interpretation of the above quote was not that Nanasipau'u was intent on pursuing the royal sons, but that she was only ever going to marry at the right level, something people have said she insists upon for her own children. The 'right level' can, of course, be interpreted differently depending on how one measures suitability for marriage, but few people could doubt Nanasipau'u's suitability to marry a prince of Tonga, and that is what she did in December 1982, giving birth to their first child, Princess Angelika, less than a year later in November 1983.[46] In September 1985, their second child, Prince 'Ahoeitu (now Crown Prince Tupouto'a 'Ulukalala) was born, followed by the birth in April 1988 of Prince Viliami (now Prince Ata).[47]

Tongan perspectives on the role of the Queen Consort

-

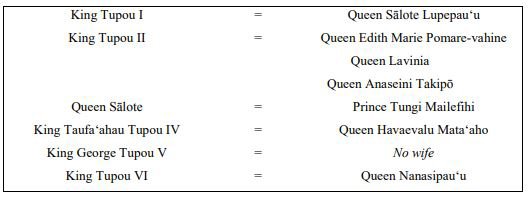

The role of the consort is not one that has been widely written about in Tonga. Indeed it is often the case across the world that the wives of kings and presidents, as they have tended to be (and usually still are, men), are seen as simply an appendage to their husbands. Such a view is both unfair and incorrect, and no less so than in Tonga where the consort is integral to Tongan kingship and plays a powerful role in the broader Tongan kinship system in which kingship is grounded (see Table 5).

Table 5. Consorts of the Tongan monarch

Source. Developed by the author after interviews and conversations with various interlocutors

-

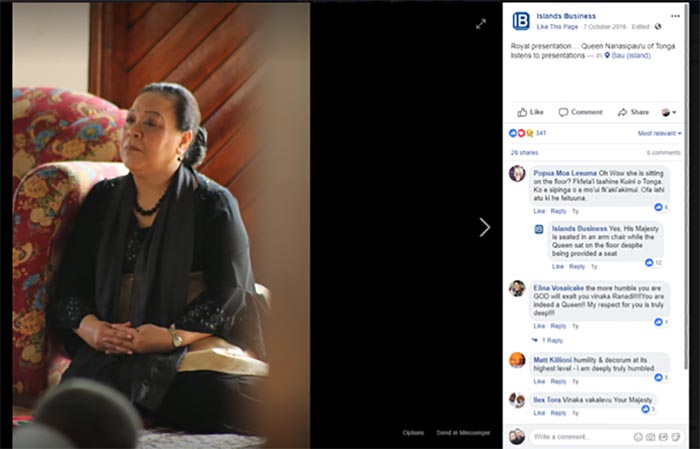

Many people I interviewed shared their thoughts on either Queen Nanasipau'u herself, previous queen consorts, or, on the role of the consort in general. One strong theme that arose in my research, was that it is important to Tongans that the consort be humble, acting in a way that elevates the King and monarchy rather than themselves. Falekava Kupu explained that Queen Nanasipau'u is respected for being 'humble' in the way she undertakes her role, explaining that 'the King is a descendant of Tangaloa, he is sacred. His wife is important, but not like the King. The Queen never assumes she's too important. She undertakes her role graciously and always acknowledging the King is the sacred ruler'.[48] 'Akanesi Palu-Tatafu supported this, saying that 'the more humble the Queen is, the more the people love her. The more humble she is, the more she elevates the status of the King and the monarchy'.[49] This idea is supported by a Facebook photo (see Figure 5 below) showing Queen Nansipau'u seated on the floor at an event. One comment on the photo says 'Oh Wow she is sitting on the floor?', to which another person replies, 'Yes, His Majesty [King Tupou VI] is seated in an arm chair while the Queen sat on the floor despite being provided a seat'. Another person adds 'the more humble you are GOD will exalt you'.

Figure 5. Queen Nanasipau'u, seated on the floor, listens to presentations.

Source. Islands Business Facebook page. Information publicly available from: https://www.facebook.com/IslandsBusiness/photos/a.610888722424431/610916859088284/?type=3&theater

-

There were four common themes about the role of the queen consort that emerged in my interviews with Tongan people. The first was that the queen consort fulfils an important function as the 'other half' of the King (in a society that is very focused on heterosexual and child-producing kinship); second, the queen consort assists the King in maintaining the monarchy and ensuring its survival; third, the queen consort has a role in strengthening the nobility (herself being a noblewoman means she understands, and is loyal to, the place of the nobility in Tongan society); and fourth, the queen ensures there is balance in the royal household simply by being able to do things and relate to things in a way that the King is not able to (either due to perceptions of his sacredness, his position as the son of another King, the limits of his experiences outside of the royal court, and the fact he is a man who cannot understand the business that pertains to women).[50] In one interview it was explained to me that Tongans see the role of the consort queen as an important acknowledgement that the monarchy can only survive into the future if it has the right kinship relations.

If the King chooses not to marry a senior [noble] woman, as G5 [King George Tupou V] chose not to, people will wonder if he does not care about continuing the purity of the line of the monarchy. Mind you, in G5's case not marrying at all was probably a better move than marrying a commoner or marrying a palangi, as that would have been an insult to the nobility, and some might say it could have 'contaminated' the bloodline.[51]

She continued,

[King George Tupou V's] reign was unusual. We had never had a King without a wife or children. At first, we didn't know who to acknowledge in the way we would if the King had a wife. Was it his mother [Queen Halaevalu Mata'aho, the Queen Mother] or his sister? [Princess Pilolevu]. The wife kind of balances things out and without her things don't quite make sense.[52]

-

Queen Nanasipau'u was seen as eminently suitable to be the wife of a prince (or King) because not only was she was someone who was raised as a potential suitor to a future King, she was someone 'the nobility could genuinely say to the royal family "here is a most suitable bride" now the ball is in your court'.[53] In a sense, she was raised to be a potential bride of a royal to keep the link strong between the nobility and royalty, and also to keep the 'bloodline' pure. Interestingly, it is often seen as one of the roles of the queen (consort and regnant) to guide the royal family and nobility to make appropriate marriage alliances.

Queen Sālote played a key role in bringing together noble families and arranging marriages where possible to bridge alliances between families. To a lesser extent Queen Halaevalu Mata'aho did the same, and … I think Queen Nanasipau'u would be a very good alliance maker because she knows the history and she knows who is who. She has an exceptional appreciation for the subtlety of rank and relationship in the Tongan context.[54]

-

The Queen's personal status as wife of the monarch carries a number of important obligations. While her rank changes relative to some other members of the royal family in different contexts, it is never higher than that of the King who is only outranked in one rare context, by his older sister and her eldest daughter, because the King's body has an intrinsic level of tapu and mana that elevates him above all other living Tongans. And while the Queen is not the second highest ranked person in Tonga in all cases, her position as the other half of a partnership that upholds the monarchy is one that is highly valued by many Tongans.

-

Our new King may do the same [as his older brother and father before him] and become the King he was meant to be and lead us into a new era of change. His wife [Queen Nanasipau'u] will become as God intended, as Her Majesty Queen Halaevalu Mata'aho became, the heart of our nation.[55]

-

Indeed, rather than simply being the one who carries the children of the King, and therefore ensuring the survival of the family line, the Queen is the primary person Tongans see as supporting the King to perpetuate the existence of the monarchy that is embedded in broader relations of kinship.[56]

Notes

[1] This depends upon whether one sees the promulgation of the 1875 Constitution as the 'official' beginning of the Tupou line, or whether it begins with elevation of Tupou I to the Tu'i Kanokupolu title in 1845.

[2] Baron Vaea was Tongan Prime Minister from 1991 to 2000.

[3] Vaea is both the title and the name, although the prefix 'Lord' has been used since the reign of King George Tupou V (2006–2012) before the names of all Nobles.

[4] Interview with Falekava Kupu, December 2012.

[5] Elizabeth Wood-Ellem, Adrienne Kaeppler and others use these words both together and separately to mean the same thing, that is the rank one has based on the rank of one's blood ancestors.

[6] Andy Mills, 'Bodies permeable and divine: Tapu, mana and the embodiment of hegemony in pre-Christian Tonga', in New Mana: Transformations of a Classic Concept in Pacific Languages and Cultures, edited by Matt Tomlinson and Ty P. Kaāwika Tengan, pp. 77–106, Canberra: ANU Press, 2016, p. 79. DOI: 10.22459/NM.04.2016.

[7] Mills, 'Bodies permeable and divine: Tapu, mana and the embodiment of hegemony in pre-Christian Tonga'.

[8] Interview with Lord Fusitu'a, July 2012.

[9] Although some members of the broader royal family in recent years have married commoners, these members were less senior in the Line of Succession. The only recent example of a senior member of the royal family marrying a commoner is that of Prince 'Alaivahamama'o.

[10] Interview with Manutu'ufanga Naufahu, July 2015.

[11] Interview with Manutu'ufanga Naufahu, July 2015.

[12] Interview with Manutu'ufanga Naufahu, July 2015.

[13] I have heard a range of opinions on what is close and what is 'too close' when it comes to marriage in Tonga. The general position appears to be that first cousins no longer marry (although this was not uncommon in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries).

[14] Interview with Manutu'ufanga Naufahu, July 2015.

[15] George E. Marcus, 'The nobility and the chiefly tradition in the modern Kingdom of Tonga', Memoir No. 42, Journal of the Polynesian Society 87(2) (1978): 1–166.

[15a] Personal communication with Manutu'ufanga Naufahu, 4 September 2018.

[16] Interview with Falekava Kupu, December 2012.

[17] Helen Lee, Becoming Tongan: An Ethnography of Childhood. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1996, p. 23.

[18] Lee, Becoming Tongan: An Ethnography of Childhood.

[19] Lee, Becoming Tongan: An Ethnography of Childhood.

[20] Hixon, Sālote, Queen of Paradise.

[21] Elizabeth Wood-Ellem, Queen Sālote of Tonga: The Story of an Era 1900–1965, Auckland: Auckland University Press, 1999, p. xv.

[22] That is, the orders or precedence in many monarchical systems, such as those in the United Kingdom, Spain, Sweden and Thailand, for example.

[23] A sequential hierarchy of nominal importance of people or items.

[24] Guy Powles, Political and Constitutional Reform Opens the Door: The Kingdom of Tonga's Path to Democracy, Suva: University of South Pacific Press, 2013.

[25] Christina Toren, Making Sense of Hierarchy: Cognition as Social Process in Fiji, London: Athlone Press, 1990.

[26] Table of Precedence available on Debretts, Online: www.debretts.com/forms-of-address/hierarchies/table-of-precedence-gentlemen.aspx (accessed 18 June 2018).

[27] Richard Eden, 'The Queen tells the Duchess of Cambridge to curtsy to the "blood princesses"', Telegraph, 24 June 2012. Online: www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/theroyalfamily/9351571/The-Queen-tells-the-Duchess-of-Cambridge-to-curtsy-to-the-blood-princesses.html (accessed 12 January 2016).

[28] Eden, 'The Queen tells the Duchess of Cambridge to curtsy to the "blood princesses"'.

[29] Elizabeth Wood-Ellem, Queen Sālote of Tonga: The Story of an Era 1900 – 1965, Auckland: Auckland University Press, 1999, p. 104.

[30] Adrienne Kaeppler, 'Rank in Tonga', Ethnology 10(2) (1971): 174–93, p. 174. DOI: 10.2307/3773008.

[31] Lee, Becoming Tongan, p. 23.

[32] Interview with Falekava Kupu, December 2012.

[33] Mills, 'Bodies permeable and divine'.

[34] The Māori and Cook Island Māori words for genealogy.

[35] Interview with 'Akanesi Palu-Tatafu, July 2015.

[36] Ana is a pseudonym used at the request of my interlocutor.

[37] Interview with Ana, December 2012.

[38] Interview with Manutu'ufanga Naufahu, July 2015.

[39] Interview with Ana, December 2012.

[40] James Ockey, 'Monarch, monarchy, succession and stability in Thailand', Asia Pacific Viewpoint 46(5) (2005): 115–27. DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-8373.2005.00267.x.

[41] Ockey, 'Monarch, monarchy, succession and stability in Thailand'.

[42] Indeed her son, Crown Prince Tupouto'a 'Ulukalala will one day be King himself.

[43] Interview with Seini (pseudonym used), July 2015.

[44] Interview with 'Akanesi Palu-Tatafu, July 2015.

[45] Interview with 'Akanesi Palu-Tatafu, July 2015.

[46] Interview with Princess Angelika Tuku'aho, July 2013.

[47] Interview with Princess Angelika Tuku'aho, July 2013.

[48] Interview with Falekava Kupu, December 2012.

[49] Interview with 'Akanesi Palu-Tatafu, July 2015.

[50] These developed from my field journal notes gathered from June 2011 to December 2014.

[51] Interview with Ana, December 2012.

[52] Interview with Ana, December 2012.

[53] Interview with Ana, December 2012.

[54] Interview with Manutu'ufanga Naufahu, July 2015.

[55] Frederica Filipe, 'A princess diary: Part II', The WHATITDO.com: Urban Island Review, 30 March 2012. Online: www.thewhatitdo.com/2012/03/30/a-princess-diary-part-2/ (accessed 30 March 2012).

[56] Interview with Ana, December 2012.

|