|

Intersections: Gender and Sexuality in Asia and the Pacific

Issue 47, July 2022 |

|

Repression, Precarity and Autonomy in Sadia Abbas's The Empty Room Goutam Karmakar and Payel Pal Introduction: Status of women in Pakistan Women and their identity constructions in Pakistan are inordinately determined by the matrix of a rigid institutionalised patriarchy operating through religious, familial and customary social discourses. The cultural mind-set overwhelmingly interspersed with orthodox religious dogmas has been instrumental in positioning women as second-class beings within the private and public spheres. Our article gains significance in the context of these long-continuing debates on the questions of female equality, emancipation and feminism in Pakistan. Here, we study the US-based Pakistani writer Sadia Abbas's debut novel The Empty Room (2018) as a telling portrayal of the everyday struggles of Pakistani women against the deep-seated patriarchal ethos in family, marriage and the larger society. Set in 1970s Pakistan, a time that marked the possibility of redeeming the state of Pakistan from the grip of conservative forces, the novel centres on the repressions and confrontations of a newly married woman, Tahira. Through Tahira's tumultuous experiences in marriage, Abbas's novel offers a stark commentary on several unspoken and unhindered concerns that the marital institution unleashes even on urban and educated Pakistani women. Accordingly, we develop a critique of marriage as one of the essential institutions through which patriarchal ideologies are perpetuated at individual and social levels. We analyse how Tahira's identity and subjectivity are continually shaped by the social expectations and norms of family respect and honour,[1] and how Tahira's experientialities are representative of all those Pakistani women who are trapped in emotionally draining marital relationships. In line with this, we also delineate that though many Pakistani women are often forced to lead reclusive lives, some, like Tahira, search for a space of their own in which they can find healing vibes and scopes of self-exertion. In depicting Tahira's lived realities and eventually her resistance to patriarchal oppression vis-à-vis recourse to art, we underscore her feminist stance and also attest to the enormous potential of art and literature that can act as recuperative means for the subjugated and the battered. Since Independence in 1947, religion and patriarchy have been insidiously juxtaposed to impinge on the notions of gender equality in Pakistan. Time and again, several laws and protective measures have been issued to guarantee women's rights to equality. However, the emergence of political fundamentalism in different phases has proved detrimental to those initiatives in Pakistan. In 1961, the Muslim Family Law Ordinance (MFLO) was enacted to put a check on harmful practices in domestic spheres and ensure transparency and accountability in marital relationships. Quintessentially, 'it instituted specific protections for women entering into marriage by establishing a minimum marriage age of 18 for males and 16 for females.'[2] In addition to this, the Constitution of Pakistan of 1973 also endorsed women's rights and equality in marriage.[3] However, with the rise of autocracy under General Zia-ul-Haq's leadership in 1977 and the imposition of the Hudood Ordinances (1979), legal measures to ensure female equality were ignored. The Federal Shariat Court was formed in 1980 with the mandate to evaluate any law that may be contrary to Islamic precepts. General Zia-ul-Haq's (1977–88) regime legitimised gender discrimination in its worst forms, truncating the few existing legal protections and usurping women's rights to law and dignified survival. The Pakistan Penal Code was then side-lined, and the dictates of religious militarism took the forefront. With the enactment of the Hudood Ordinance in 1979 as part of Zia-ul-Haq's Islamist political rule, the predicament of Pakistani women was pushed to the mercy of an unabashed patriarchal regime. It is worth noting that 'the Hudood Ordinances criminalised all consensual sexual intercourse between adults outside marriage; female minors could also be charged with zina (extramarital sexual intercourse) if the age of puberty was reached.'[4] As a direct consequence 'family members were able to bring spurious adultery and fornication charges against women under these laws and to punish women for refusing arranged marriage or seeking a divorce.'[5] Thus, these ordinances, in reality, jeopardised the healthy living conditions of Pakistani women because law, religion and patriarchy were dangerously circumscribed to punish women for any kind of dissent or transgression. In 2006, the Women's Protection Act revised the Hudood Ordinances, revoking most of its menacing clauses. Despite such repeal, a misogynistic temperament was imposed on the social psyche, causing women to suffer greatly in marriages.[6] Given that patriarchal ideologies prevail in an overarching manner, laws seem to lack adequacy, thereby often failing to safeguard ordinary women's rights and guarantee a dignified livelihood. Consequently, Pakistani women's status has deteriorated, and they have become increasingly vulnerable over time. The report of the International Crisis Group on the persisting heinousness of systematic violence against Pakistani women concludes that, notwithstanding the 1973 constitutional guarantee of safety for all citizens irrespective of gender, legislative advancement to effectively address the issues of inequality endured by women has indeed been inconsistent.[7] Violence and violation of women continue to be ubiquitous in Pakistan. In such a context, feminist voices have arisen against the orthodox political and patriarchal systems in Pakistan in different phases since its inception, but 'the feminist movement [altogether] remains controversial in Pakistan' till today.[8] The cartography of feminism in Pakistan has been never so static, as Rubina Saigol (2016) aptly states:

The early years of feminism after 1947 were firmly reform based. For instance, in 1948, 'thousands of women marched to the Assembly chambers shouting slogans, led by Jahanara Shahnawaz and other women leaders [compelling] the Muslim Personal Law of Shariat [in] recognizing women's right to inherit property'[10] Women's rights are also protected by international laws and treaties, such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) and the Convention for the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), both of which Pakistan ratified in 1996. CEDAW is among the most significant standards prohibiting acts that exacerbate women's social inequalities. However, poor administration, the absence of the legal framework, and prejudiced policies, consolidated with an overarching regulatory environment of gender inequalities, result in inadequate protection for women.[11] While the 1980s witnessed the popularity of secular feminism in the form of public protests against the Islamic fundamentalist policies of Zia-ul-Haq, in the 1990s and 2000s, various NGOs and funded activism came into being, with women's protests and street marches taking a backseat. Notably, the widespread movements in recent times, such as that of '#MeToo' and the 'Aurat' March (in 2020 and 2022), mark a resurgence of the public outbursts of feminism, this time stridently against the masculinised ideologies of the state, capitalism and society. #Metoo was first used in 2006 by American activist Tarana Burke, but it gained popularity in 2017 when actor Alyssa Milano used the hashtag metoo on Twitter to share her personal story of sexual abuse and motivate other women to speak out against physical harassment. In Pakistan, too, the #MeToo movement gathered momentum, and women from many walks of life shared their experiences with gender discrimination and sexual violence.[12]

Figure 1. Representational image of the MeToo movement. Source. Photographed by Manisha Mondal in Naila Inayat, 'Pakistan media's support for #MeToo ends when one of their own is accused,' in The Print (December 2019), online: theprint.in/opinion/letter-from-pakistan/pakistan-media-support-for-metoo-ends-when-their-own-is-accused/330626/, accessed 12 Feb. 2022. On International Women's Day for the previous few years, Pakistani women have marched for their rights. The reactions to these Aurat Marches range from mild criticism, ignorance, and misinterpretation on one end of spectrum to bitterness, hatred and shame on the other. Movements such as the Aurat Marches have what Amrita Basu refers to as 'feminist underpinnings,' which is when a women's movement has feminist objectives.[13] However, for the conservative section of Pakistan, feminism continues to be a 'foreign import and a hobby of elitist women who wish to imitate western culture while rejecting their own traditions and religion.'[14] In Pakistan, the civil law, which is partially founded on religious traditions, is implemented within a secular, procedural framework.[15] Lisa Hajjar highlights that despite the fact that Sharia[16] (Islamic Law) is crucial for comprehending family interactions in Muslim communities, the assumption that Islam or any religion explains social structures has been heavily criticised.[17] At the same time, feminism in Pakistan is considered by many as a subversion/derogation of indigenous cultural and religious norms. Also, there remains an ideological divide between the Islamic feminists and the secular feminists—the former group emphasising religion to substantiate the causes of women's equality and the latter group attesting to questions of body, dress code, reproductive rights and sexuality in general terms. Given such diversifications, renowned feminist thinkers and writers such as Rubina Saigol, Farzana Bari and Farida Shaheed enunciate that the overall discourse of Pakistani feminism needs to be conceived 'as a movement shaped by [Pakistani] women reacting to their circumstances' by virtue of which 'a [Pakistani] woman facing violence on the daily [basis], attempting to change the customs, values, and norms that legitimise violence against women, is a feminist.'[18] Accordingly, the lived realities and experientialities of Pakistani women become crucial in deconstructing the 'ambivalent positioning [of these women] within religion, society and politics, and family'[19] at different points of time and history.

Figure 2. Pakistani activists rally for women's rights on International Women's Day in Lahore on 8 Mar. 2019 Source. Photograph: Arif Ali/AFP/Getty Images in Hannah Ellis-Petersen, 'Pakistan's #MeToo movement hangs in the balance over celebrity case,' in The Guardian, (January 2021), https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2021/jan/01/pakistans-metoo-movement-hangs-in-the-balance-over-celebrity-case, accessed 12 Feb. 2022. Marriage, repression, and womanhood In Pakistani culture, marriages are generally arranged by families, as they are in most South Asian communities. For the sake of preserving family honour and status, the patriarchal heads of the family assume it to be their right to determine matrimonial alliances on behalf of their children. The traditional notion of mate selection consists of marriages arranged by the individuals' families. South Asian populations are familiar with the concept of arranged marriage, and in India, Bangladesh, Pakistan and Sri Lanka, arranged marriages are the customary practice.[20] This marriage is defined as contractual agreement, written or unwritten, between two families, rather than individuals. In such a context, 'the principle of familialism and interdependent social relationships are dominant, especially for females. The individual's interests, needs, and happiness are considered secondary to the interests of the family and community.'[21] Several studies have pointed out that arranged marriage, nonetheless, functions as 'a key instrument for economic, social, and political stability in South Asian communities'.[22] Predominantly, Pakistani culture also abides by the model of arranged marriage. Family, honour and social prestige are given utmost importance, and individual interests, especially those of women, are hardly asked for or acknowledged. Feminist thinkers like Grace Atkinson, Shulamith Firestone, Adrienne Rich and Carole Pateman have criticised traditional gender-structured marriages for culminating in an experience and understanding of the significant financial, affective and bodily implications for women. The primacy of marriage in patriarchal society, the marginalisation of women's labour, and gendered hierarchies have all been correlated with the precarious nature of marriage for women.[23] The plight of most Pakistani women in marriage is no exception to these intersectional modes of oppression. Through the decades, Pakistani women writers have addressed these issues and engaged with the alarming questions of female agency, body and rights in marriage. Some of such notable works include Bapsi Sidhwa's The Pakistani Bride (1983), Kishwar Naheed's The Distance of a Shout (2001), Aamer Hussein's edited Kahani: Short Stories by Pakistani Women (2005), Ayesha Baqr's Beyond the Fields (2019), Soniah Kamal's Unmarriageable (2019), and Amneh Shaikh-Farooqui's Fearless: Stories of Amazing Women from Pakistan (2020). In Islamic societies such as Pakistan, the responsibility of safeguarding family honour or 'ird (izzat)' falls solely on the shoulders of women. Consequently, Pakistani women are frequently married at a relatively young age and are more prone to have an arranged marriage due to patriarchal power structure and gender-based prejudices.[24] Sadia Abbas, through her debut novel The Empty Room, not only pertinently joins the polemic of women writers who address issues related to Pakistani feminism but also points out the nuances of Tahira, a young Pakistan woman's arranged marriage. This novel not only critiques the entrenched drives of misogyny in Pakistan but also ushers the effective possibilities of countering and decimating those. Abbas's The Empty Room pitches into these normative conceptions of arranged marriages in the conservative society of Pakistan and categorically deals with the voicelessness of Pakistani women through her protagonist's psychic clashes and troubles. The Empty Room begins with a married couple, Tahira and Shehzad, hesitantly 'trying to feign sleep'[25] after their wedding night, and then, within the first few pages of the novel, Abbas brings home to her readers the staunch patriarchal ideologies of Shehzad and his family, who consider Tahira as a mere trophy wife and daughter-in-law. Tahira, a talented painter, raised in an educated family, is not only looked down upon as a subservient being but also is instructed to behave like a 'good' wife in every trivial matter after her marriage. Shehzad and his family yield complete control over Tahira's identity, body, physicality and socialisation, vindicating it as their ethical duty and natural prerogative. Shamelessly, Shehzad sets on a civilisational mission to train Tahira to become an 'ideal' wife—flaunting himself as the benevolent master and Tahira, the imbecile and naïve subordinate. Unfortunately, Shehzad 'would purify her in thought as well as deed. On that rested the comfort of his family, the long-term preservation of his virtue, her own salvation.'[26] Shehzad's words and actions evince his blatant patriarchal ideology, making him perceive their conjugal union as a well-established gender hierarchy and not on equality. Studies on South Asian women's experiences of marriage have elucidated that patriarchy plays an enormous role in deciding the status and lives of women in marital relationships.[27] On examining the ambiguities of coercion and consent that South Asian women face in marriages, Aisha K. Gill and Heather Harvey[28] observe that a majority are either being compelled to or they unwittingly accept the traditional constructions of femininity, even at the cost of curtailing their fundamental rights and sense of selfhood. Tahira's narrative exemplifies this patriarchal compulsion to embrace the idealised tenets of wifehood. Tahira is relentlessly taunted, scolded and humiliated by Shehzad for her parental upbringing. With his flagrant ego, Shehzad crudely pinpoints to Tahira: 'Your parents […] have been deficient in your upbringing. We must overcome this shortcoming. I will teach you your duties but not deny your conjugal rights, which are, my religious duty as well.'[29] Not only this, Shehzad also gives her a book on the ethical conduct of a good wife and candidly boasts of his nobility:

Shehzad belittles Tahira in front of his family, at times shouting at her aggressively that 'it is not [her] place to judge the reason of [her] husband's demands.'[31] He disgraces and physically abuses her publicly for any kind of displeasure. However, Shehzad feels no shame or guilt in denigrating Tahira as he is bolstered by the cultural prescriptions of patriarchy that legitimise every form of authority on women, especially wives. It is as if 'men who assault their wives are living up to cultural prescriptions [of] aggressiveness, male dominance and female subordination.'[32] No less are the other members of Shehzad's family in harassing and disparaging Tahira. Shehzad's mother and sisters unleash patriarchal repression on Tahira in dangerous ways. Shehzad's family vilifies Tahira and incessantly throws tirades about Tahira's parents and the dowry they had sent with her, making Tahira feel extremely angry but helpless. Tahira soon realises that she is trapped in a loveless marriage marked by a heinous misogyny in which man is the ultimate judge,and a woman is evaluated according to her associations with man. Her married life is oriented on the rhetoric of hegemonic masculinity, which R.W. Connell defines as 'the most honoured way of being a man,' that requires 'all other men to position themselves in relation to it,' while also rationalizing 'the global subordination of women to men'.[33] Tahira's individuality is determined by her position relative to Shehzad's 'way of measuring'[34] where his family autocratically define for Tahira the standards of behavioural, ethical and expressive norms without ever bothering about her happiness or wellbeing. Tahira's life is horrifyingly dictated by Shehzad or his family on what to wear, with whom to speak and what to say. Her mother-in-law, Shireen, orders her to dress up gaudily with a heavily worked salwar kameez and bangles. Shireen says that 'you have to look like a dulhan [otherwise] what will people think?' [35] Shireen's command testifies to the deep-seated patriarchal structures that tend to codify and objectify women vis-ä-vis bodies and physical looks. Tahira has 'to dress ornately, lavish with jewels and her most elaborate, vivid and plush clothing'[36] and is expected to 'change the colour of her clothes'[37] in accordance with Shehzad's and his family's demands. Tahira's individuality and identity are trampled by Shehzad and his family's patriarchal expectations of womanhood and wifehood—as she is unconditionally bound to dress up, talk, think and behave as desired by them. What is surprising is Tahira's gradual succumbing to Shehzad's and his patriarchal family's torturous designs. Tahira's subjugation exemplifies the inherent inequities which radical feminist thinkers such as Shulamith Firestone, Ti-Grace Atkinson and Adrienne Rich have vociferously argued as being the hideous fallout of heterosexual relationships and the institution of marriage. While love, companionship and marriage discourses, according to Atkinson, are deceptive and coercive,[38] Rich looks at marriage as the machinery of systemic heterosexual patriarchy through which the drives of male power and masculinity are celebrated.[39] Criticising family as a locus of oppression, Firestone contends that the systemic rules of marriage and family permit men to exercise arbitrary control over women's psycho-sexual entities. Firestone's famous propositions in The Dialect of Sex thus put it:

Tahira's anguished and tormented submissions to Shehzad and his family's tantrums clearly reflect Firestone's observations. Tahira tries to do—what Firestone sees as a fundamental problem with women who 'express their individuality through [their] physical appearance'[41] and prove themselves not only 'competent' but also 'authentic'[42] to their male counterparts. So, listening to Shehzad's lectures on becoming a responsible wife, Tahira desperately attempts to show her faithful internalisation of his wisdom. Tahira ponders how to 'persuade him [to think] that she was willing to be the most dutiful of wives.'[43] Through her day-to-day activities, Tahira earnestly aspires to fulfil Shehzad's expectations, and in failing to do so every time, 'she tried apologizing, taking the blame upon herself.'[44] As pointed out by Atkinson,[45] Tahira, like any other ordinary woman, is driven to believe that Shehzad's teaching her of the appropriate notions of wifehood is his way of loving and caring for her. Consequently, whenever Shehzad accuses her of falling short of his expectations, Tahira feels ashamed of her own limitations and marriage preys on her psychological wellbeing and stability in pathetic ways, as the narrative depicts her moments of extreme despondency:

Tahira gradually develops a sharp sense of low self-esteem that cripples her from the inside. Ignored and derided by Shehzad, Tahira wonders if for Shehzad she is somewhat 'like [a] creature, who's half-woman half-cat.'[47] In this novel, Tahira's vulnerable status represents all those Pakistani women whose sense of selfhood, identity and freedom are threatened by male-governed marital institutions. It is important to note that marriage is a fundamental institution in Pakistan and is regarded as a significant moral and social responsibility, and that the regulations and customs governing marriage are crucial to women's overall well-being.[48] Tahira's obligations to Shehzad and his family upstage her psychological stability, disrupting her sense of autonomy and mental well-being. Tahira is bound to silently endure her in-laws' rebukes, teases and blames—as according to the social custom a daughter-in-law must learn to adjust and adapt in the new household. Tahira's in-laws ridicule her painting skills and mock her as a misfit for a husband like Shehzad, leaving her to adjust to a piercing misogyny and struggle to find avenues to contest or escape from such a corrosive atmosphere. The dysfunctional nature of Tahira's marriage has been attributed to the predominance of patriarchy, the devaluation of women's labour (here her painting skill), and the hierarchical structures of gender.[49] While sharing her views on the genesis of this novel in an interview with Shireen Quadri, Sadia Abbas states that:

Tahira realises that women are responsible for the emotional closeness of their families, for adapting their sexual fantasies to those of their male partners, for managing interactions and settling disagreements from a subservient position, and for being as flexible as possible without putting their husbands' patriarchal views at risk.[51] Her realisation, resulting in frustrating experiences with Shehzad, who hardly matches her artistic talents and sensibilities, testifies to the everyday confrontations of Pakistani women with the orthodoxies of family and society. Tahira appears to know that, in line with the stipulated standards of honour, she will be required to sacrifice her autonomy and independence and aspirations for the sake of her marital relationship and in-laws' home. If she fails to do so, however, consequences for disobedience will be perceived as an act of selflessness that favours Shehzad at the expense of her freedom.[52] Tahira's marriage entangles her so viciously that her desire for individual autonomy seems to be subsumed under the grand doctrines of social prestige and family honour. Patriarchy, precarity and vulnerability The concept of precarity, rooted in feminist politics, can be identified in Judith Butler's post-9/11 writings. Butler began using the term 'precariousness' to correspond to the inherent precariousness of human existence. As she argues,

The lives of those perceived to be of no importance by the dominant are intrinsically volatile, as they exist in a state of precarity. Thus, precarity applies to all possibly disempowered 'others.' The fact that Tahira's life is governed by her husband and his family provides a culturally determined interpretation of how gender is conceptualised in Pakistan. By being considered as the 'other,' Tahira's precarious condition encompasses her painful experiences that unravel the difficulties of retaliating against oppressive patriarchy in a society in which respectability and family honour are primarily associated with women and their status in marriage. Tahira, despite being continually humiliated, has to continue her marriage with Shehzad, an abusive husband and he malicious in-laws, resulting in her psychologically battered and devastated self. Stuck in a poisonous marriage, Tahira, after a few days, 'dreads [Shehzad's] silence as much as his conversation.'[54] Tahira cannot articulate her sufferings and, after a certain period, is left with no other option but to be 'brave in a way that exhibited fortitude without fuss and display, without bids for intrusive and shaming public sympathy.'[55] Even if Tahira thinks of a refuge, there is no place to do so. Tahira is well aware that her paternal family places a higher value on obedience and the fulfilment of duties and obligations than on the rights of individual family members.[56] Tahira ensconces herself that 'no matter what she said, people—here her family and society became one, blended into a great, judging, terrifying mass—would think she had deserved it.'[57] And to make matters worse, her own family members, who considered themselves to be so distinctive, would believe she had done something to deserve it. Tahira's precarious condition, in Butlerian discourse, 'directly linked with gender norms, since we know that those who do not live their genders in intelligible ways are at heightened risk for harassment and violence.'[58] This observation can be supported through the study of the mental health of Pakistani women by Unaiza Niaz, which states that due to sociocultural constraints, women in Pakistan are trapped in unhealthy relationships and are unable to seek refuge from their abusers. Due to the fear of being ostracised as a divorcee, which is akin to becoming a social outcast, parents do not advise their daughters to come back home.[59] While Tahira's brother, Waseem, an enthusiastic supporter of socialist and egalitarian ideas, can sense her unhappiness and wants her to come out of such emotionally frustrating wedlock, Tahira's mother, Mariam, does not support her. Mariam expresses her worries and anxieties about social disgrace and stigma, which can affect the future of Tahira's unmarried sisters. Mariam outbursts to Tahira that 'you know that wrong or not, there's little to be done. What about Seema and Nilofer? Who'll marry them? And, even if I do something, then what? You know how divorced women are treated.'[60] This implies that the vulnerability and insecurity expressed by Tahira are noticed in her mother too as they both are conditioned, adversely affected, and controlled by political structures. Here precarity becomes, as Isabell Lorey argues, 'the striation and distribution of precariousness'[61] and the 'hierarchized difference in insecurity [which] arises from the segmentation, the categorization, of shared precariousness.'[62] The worth, involvement and variability of the term emerge from its combination of these two distinctly different perceptions: a toxic marriage for Tahira and shame and stigma for Mariam. Precarity in this context refers to the inherent risk, vulnerability and destabilization of socialisation, making reference to the malleable and traditionally changeable methodologies that amplify the understanding of vulnerability at particular points in time and compel Tahira and Mariam to acknowledge their heavy reliance on the others. Mariam's fears are rooted in conservative ideologies that thrive on the social constructs of honour and shame, forcing many South Asian women into marriage and also to continue with challenging relationships.[63] Thus, within Pakistani society, which exemplifies a case where customs, religion and law operate in an intertwined fashion to shape the rights of women,[64] marriage is more about unswerving female obedience and commitment to the husband's family. Symbolically, a woman is considered the cultural repository of family honour and, accordingly, her flaws and frailties are conceived as responsible for the loss of honour of the entire family.[65] Repudiation of marriage is mired in layered social castigations which ultimately deter many women from divorce. In this novel, Mariam's dispassionate attitude towards Tahira's sorrows and grudges reveals the obligations that women consider normal in marriage and must be followed to avoid losing family honour. Though Mariam feels for Tahira, in fear of social stigma and shame, she fails to provide her with the necessary emotional support and solace. This discussion also indicates that the society of Pakistan is primarily a patrilineal one in which a woman's access to and status in her home are limited. A woman is considered to live temporarily in her father's house and then move to that of her husband.[66] In short, the proprietorship of a woman is negotiated by patriarchal heads throughout her life. More than being perceived as an individual with her own rights, a woman's identity in Pakistan is contextualised in accordance with either her father, her brother, or later her husband—an intriguing fact that Gayle Rubin tellingly sums up as 'women are given in marriage, taken in battle, exchanged for favours, sent as tribute, traded, bought, and sold.'[67] Expectedly, against such constricting attitudes in Pakistani society, Tahira is forced to carry on her fractured relationship with Shehzad. Helplessly, Tahira once utters to her mother:

Tahira comes to terms with the fact that her parents are no exception to the pervasive social conditioning that 'a female belongs to [husband's house] … and is therefore a temporary visitor in the house.'[69] Sadly, Tahira starts accepting that for her parents she is not 'an asset, although she may be fondly treated'[70] and therefore has to live a life of compromise with Shehzad. The ruling belief in Pakistani culture (much like that of India) about a daughter is that she is 'only a "visitor" in the house where she is born and that, eventually, she has to go to her "real" or married home and, whatever unfavourable [things] happen, there is no place [for her] outside the house of her father, guardian or husband [and] at her husband's house, her only role is of a housekeeper and a child bearer.'[71] Strangely, the precarity of girl children continues to exist in the cultural psyche despite an 'increased access to education and information.'[72] Steadily increasing marital contentment and transition improves women's mental wellbeing, but excessive levels of unpleasant experiences can impair family cohesion and lead to chronic common mental disorder (CMD). Ilyas Mirza and Rachel Jenkins conducted a comprehensive assessment of twenty surveys undertaken in both rural and urban areas of Pakistan and found that the average proportion of psychological distress in the community is 34 per cent. For women, the range was 29–66 per cent, while for men it was 10–33 per cent. This survey brings out the fact that the paucity of comfort relationships, alongside marital conflicts, abuse and harassment by in-laws, too many kids, and financial barriers are detrimental to the mental well-being of Pakistani women.[73] In such circumstances, family support can effectively prevent mental health problems by improving marital happiness and readjustment as well as reducing negative encounters in marriage.[74] Unfortunately, in the case of Tahira, her family fails to give that kind of emotional support, and Mariam, her mother, urges her to maintain faith in Shehzad and never leave his household even if she is mistreated and degraded. As a daughter, Tahira, according to Linda Thompson and Alexis J. Walker, does not always provide the happiness or sense of meaning that the vision of motherhood promises. Mothering, on the other hand, is shaped by the persistent idea of motherhood as a never-ending and total responsibility. Mariam seems to assert that 'the tension between the constant-and-complete responsibility and the have-it-all images of motherhood creates ambivalence in mothers.'[75] As the years pass, Tahira's experiences of wifehood and later motherhood happen to be quite unfulfilling and mentally cumbersome. After Tahira and Shehzad have their children, Tahira's in-laws categorically remind her of the responsibilities and obligations of motherhood. They attempt to indoctrinate her on the supreme moral duties of a mother. While Tahira remains burdened with childcare duties (and sometimes has to enlist the help of her parents), Shehzad happily starts philandering with other women. Notoriously, Shehzad's toxic masculinity and its manifestations escalate day by day. Shehzad cherishes his extra-marital affairs and conceives those as justifiable, given that Tahira remains busy with domesticity and children and cannot gratify his demands properly. Shehzad's infidelity not only steadily weakens the marital bond, but also leads Tahira to believe that all of her endeavours will be in vain. This emotional upheaval is akin to Arthur Schopenhauer's concept of sexual impulse:

Shehzad expects absolute subservience and fidelity from Tahira, while vindicating his wrong doings as 'wasn't it [Tahira's] duty to make things smoother for him, to relax him at the end of the day, to know his desires before he knew them himself?'[77] Shehzad's masculine selfishness and egotistical temperament exemplify the traditional patriarchal ideologies that associate men with authority and women with passivity. A heart-wrenching account of a middle-class housewife, Tahira, Abbas's novel unfolds how hazardous it becomes to rediscover/reassert oneself in a patriarchal culture. Tahira's victimisation underlines the systemic violence that is endemic in orthodox family structures and that disempowers women quite surreptitiously. On meeting Andaleep, a bosom friend, Tahira feels an urge to speak and share her grief and remorse, but strangely, 'words seemed paltry and hopelessly, absurdly inadequate.'[78] The protracted suppression has robbed Tahira of the power to speak for herself. Instead, she feels 'ridiculous [,] ostentatious [and] old'[79] in comparison to the 'undefeated and outrageous'[80] Andaleep. Tahira's shakiness and inarticulateness typically reflect the impact of the silent coercion of patriarchal hegemony and its tolerance. Feminist perspectives have very often identified this issue: while 'the root cause of violence lies in an unequal power relationship between men and women that is compounded in male dominated societies,'[81] the disturbing fact is its being considered a 'norm … culturally and legally accepted or tolerated.'[82] There seems to be a sanction on the tyranny of the male partner by the family and society. In this novel too, Abbas delineates how Tahira's acceptance and endurance of patriarchal coercions make her lose her faith in her capabilities and talents. After a few years, when Tahira tried to 'seriously to begin painting again, she found her chief obstacle was not Shehzad or Shireen … but memory … [and] an engulfing sense of loss.'[83] A repressive marriage has beleaguered Tahira's artistic visions and calibre, miserably reducing her to a mere family caretaker. Years of doing only household chores, nurturing children and spending most of the time in the kitchen have destroyed her aesthetic acumen. Marriage, as articulated by Carole Pateman, functions as an insidious instrument of 'capitalist patriarchy'[84] for Tahira, where the husband has a housewife expected to take care of all domestic chores and provide ceaseless labour. Tahira's trajectory in Shehzad's house exemplifies the typical non-egalitarian family set-up, where 'married women must perform domestic chores for their husbands.'[85] These dynamics subsequently consolidate 'a more powerful position for men within the family and compounds women's economic vulnerability.'[86] For Tahira, recuperation from a tortuous marriage happens to be a rigorous journey in itself. She has to disentangle herself from Shehzad's male authoritarianism and find a space of her own that is long lost in household chores and duties. Artistic autonomy and self-healing A feminist interpretation of the notion of autonomy specifically necessitates narratives of women who struggle against patriarchal restraints to articulate and reimagine their innermost convictions and perceptions of self in intrinsically or uniquely feminine contexts.[87] Abbas's novel narrates one such story where Tahira is a victim of an atrocious marriage, which truncates her identity, expressive abilities, subjective agency and basic desires. However, the novel is not only about Tahira's stifling experiences, but it also marks a triumphant note in showing her overcoming the distressful conditions. Tahira finds herself engulfed in a tormenting marriage, and Andaleep, her dear friend, inspires her to take up painting and involve herself in creative activities, which would perhaps provide some respite to her afflicted mind. With the aid of Andaleep, Tahira embarks on a journey of autonomy and self-healing through art and eventually manages to regain her autonomy and artistry. Theresa Van Lith, Patricia Fenner and Margot Schofield, in their study on art therapy, state that the 'lived experience of art,' generating as a companion to the psychosocial rehabilitation and the healing process of mental health, symbolises the significance of atmosphere in a creative therapeutic setting with a secure and welcoming environment that supports individuals to express and address emotional distress. Art in this context tends to have positive effects through facilitating inner transformations by fostering hope, healing, independence, consciousness and connectedness.[88] Tahira also experiences inner transformations as soon as she starts painting in the old studio of her father's house, and after a few days she becomes 'surprised to have discovered an earlier stubbornness, which she thought had disappeared since marriage.[89] Tahira feels reinvigorated every time she paints. In one of her visits to an art exhibition, Tahira manifests her joy to Andaleep: 'The collection is so wonderful. It always lifts my spirits.'[90] Here Tahira echoes Wildean aphorism, 'Man [sic] is least himself when he talks in his own person. Give him a mask, and he will tell you the truth.'[91] Art, For Tahira, becomes that mask that allows her to articulate experiences when she loses debating skills and when her utterances are inadequate to explain her innermost feelings. Heather L. Stuckey and Jeremy Nobel's research demonstrates that participation in artistic activities, either as a bystander of the creative endeavours of others or as a catalyst of one's own creative output, can improve one's affective states, emotional responses and other mental functioning, as well as have a significant effect on significant physiological characteristics.[92] In a similar way, the act of painting rejuvenates Tahira, offering her a renewed engagement to get some mental relief from her troubled marital life. In the course of time, Tahira also goes back to her avid reading habit, which inculcates in her a motivation to pursue and cherish art with new vigour. Tahira's exposure to art and literature restores in her a yearning to accomplish something beyond the mundane drudgery of life. There occurs a transformation in Tahira's life—she comes out of her numbing pain, isolation and self-humiliation and starts celebrating life through art. The novel beautifully depicts Tahira's psychic revival after years of degeneration:

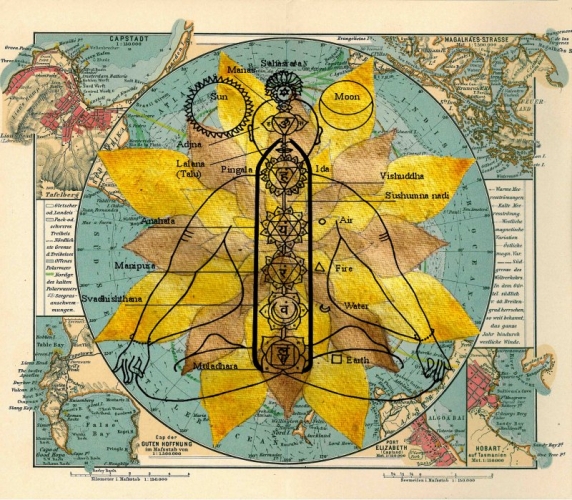

Essentially, painting transports Tahira to a space of self-contemplation and self-absorption. Painting acts as therapy for Tahira—enabling her to articulate her mind and affirm her own individuality. As part of the World Health Organization's Solidarity Series of Events, the Healing Arts initiative demonstrates how artwork may heal specific traumatic experiences. Figure 3 shows an example of such a painting and its implications:

Figure 3. Experience of a participant in a guided meditation on colour in Sam Gilliam's 10/27/69, led by Sabrina Sarro: 'I want to invite everyone to pay attention and to lean into the color all around us. Colors that we might not have language for yet. The colors that resonate with us—to really lean into the energy and the language of colors all around us.' Source. Jackie Armstrong, 'The healing power of art: Listen to meditations, reflections, and somatic exercises around art and well-being,' in MoMa Magazine (Sep. 2021), online: www.moma.org/magazine/articles/629, accessed 10 Dec. 2021. Likewise, art becomes the symbol of 'humanist paradigm' for Tahira, a term used by Jean Grimshaw in his discussion on autonomy and feminist thoughts. Grimshaw asserts that this humanist paradigm 'conceptualise[s] the need women have experienced for this greater degree of autonomy and control, for overcoming the fragmentation and contradictions in their lives, and for a capacity for self-definition.'[94] Notably, artistic autonomy helps Tahira re-establish an intrinsic version of her own self—one which is not determined by the demands/dictates of her family, husband, mother-in-law, and society. Historically, pictures, stories, dances and music are often seen to have played an enormous role in healing individuals/communities from pain and trauma.[95] Contemporary studies in health psychology also corroborate that different art forms have time and again ameliorated individuals from emotional repression, stimulated self-reflection and activated new energies. As Paul M. Camic opines, 'The arts have the potential to contribute to health psychology in several areas: as a means of informal communication that could enhance clinical assessment, increase emotional capacity, expand effectiveness of social networking interventions and promote creative activity.'[96]

Figure 4. Body, Mind, and Art Therapy Source. Vishal Singhal, 'Art therapy: Healing through art,' in ArtZolo.com (October 2021), online: www.artzolo.com/blog/art-therapy-healing-through-art, accessed 5 Jan. 2022. In this novel, Tahira's re-engagement with painting makes a case for the point. Art effectively alleviates Tahira and aids her in bypassing the pressing demands of Shehzad and her in-laws. In the rigid Pakistani society in which divorce is considered a social taboo, Tahira fails to dissolve her relationship with Shehzad legally, but through her resort to art, she reasserts herself. Contrary to her earlier days when Tahira used to feel guilty for not meeting Shehzad's standards, she now feels disgusted with the external world, the domestic qualms, her children's demands and Shehzad's dominance. She utters:

Tahira, through her paintings, successfully ushers herself into a world in which she can express, create and embrace the meanings of life on her terms. For Tahira, art unfurls a new horizon of life untainted by misogynistic society. At the end of the novel, Tahira appears to be an independent woman who no longer wishes to hide or crawl in fear of patriarchal dominance, but instead cherishes a triumphant sense of accomplishment through her art. Tahira regains her self-esteem and starts experiencing her own psychosexuality intimately and viscerally—a strikingly different experience from the numbness that had plagued her for years. Fascinatingly, 'she realized, astonished, that she was angry, deeply, insanely, bloodily enraged … and her rage began to give shape to a series of compositions.'[98] What is noteworthy in Tahira's intrinsic experientiality is the development of a unique perceptiveness that inspires her to see or decipher the world exclusively through her own self and not through the parameters set by Shehzad or the larger phallocentric society. Subsequently, Tahira makes her paintings from these intricate experientialities. Her paintings come out compulsively from her pain, fury and grief. Tahira's irresistible urge to convert her deeply felt emotions to art forms can be understood through Helene Cixous's concept of the 'ecriture feminine'—a mode of representation/language informed by the 'psychosexual specificity' of women that 'empowers [them] to overthrow masculinist ideologies and to create new female discourses.'[99] Paintings for Tahira emerge as an avenue to vent out her suppressed feelings and violations and thus formulate a space for herself by ousting the patriarchal hegemonies. It is through art that Tahira 'write[s] herself … [and] put[s] herself into the text—as into the world.'[100] In a society that refutes a woman's right to articulate and assert, art in a compelling fashion provides Tahira with a new meaning of life. With her sense of self-accomplishment, Tahira develops the courage to terminate her emotionally dysfunctional relationship with Shehzad. Tahira decides to move out of Shehzad's house and raise her children in her parental home. Tahira's agency highlights that art has the capacity to 'potentially produce emotional responses that are compelling, insidious and expressive because they elude the usual verbal explanations and set up resonances among … nonverbal sensory/affective representations.'[101] Pertinently, Tahira's resurrected selfhood vis-à-vis her recourse to art aids her to refute the male-oriented social inscriptions on women's bodies and psyches and indulge in a celebration of an essential female identity, liberated and empowered. Art thus restores to Tahira a sense of stability and mental wellbeing—which otherwise would have been beleaguered by marriage and unruly social systems. Conclusion Abbas's The Empty Room brings to the forefront the complexities that enmesh the lives of ordinary Pakistani women and nuances of South Asian patriarchy in general. Tahira's repressive and precarious married life accurately depicts this image of South Asian patriarchy, which is best understood through the lens of Deniz Kandiyoti's notion of classic patriarchy, according to which 'girls are given away in marriage at a very young age into households headed by their husband's father.'[102] This traditional patriarchy produces a system in which men keep authority over women throughout their lives, as sons and sons-in-law are favoured above daughters, spouses and daughters-in-law. While the narrative hinges on Tahira and her harrowing experiences after her marriage, the novel undeniably makes a decisive intervention on the question of Pakistani women's access to the fundamental rights of autonomy and dignity even in contemporary times. Niaz claims that 'although the threshold to the 21st century has been crossed, traditional modes of violence against women have continued to grow.'[103] In delineating Tahira's disturbed marital life, Abbas's novel attests to the draconian grip of traditional gender assumptions that constrict and stifle women's lives, subjectivities and freedom in varied guises in Pakistan. While this novel is structured around 1970, it invariably is a testimony to issues related to the subjugation of and institutionalised violence against women in any other South Asian country. Conversely, this novel depicts how men in South Asia encounter a 'construction of masculinity'[104] based on their understanding of honour that in the long run becomes responsible for maintaining domestic, communal and even societal 'honour' through regulating the behaviour of daughters, spouses and mothers. Nasreen Akhtar and Daniel A. Metraux claim that 'the teachings of Islam provide full protection and security for women, but in Pakistan, the majority of women are suppressed and victimized by their own family members.'[105] The severity of patriarchal ideologies makes women's lives in Pakistan full of hurdles, and even if 'Pakistani women have the potential and capacity to excel in every field of endeavour, they very often cannot exploit their talent in this chauvinistic male-dominated society'.[106] Through Tahira's victimisation, Abbas quintessentially exposes these chauvinistic attitudes that perpetuate the gender hierarchies in Pakistan, and through her recuperation, attests to a powerful statement of feminism. Abbas's novel transcends the periodicity and evolves as a testimony to the insidious 'element of patriarchy [that] has caused a total disregard for women in the Pakistani society'[107] regardless of the era. In a broader sense, the novel has significant ramifications in that it demonstrates that institutional and interpersonal abuse are not inconceivable phenomena for Pakistani women. In depicting the far-fetched impact of autocracies of patriarchy in marriage and family on women's psychological well-being, Abbas's novel resonates with the literary as well as the other modes of social protests against gender violence, ongoing in Pakistan. As part of the greater objective of employing specific creative forms to counter patriarchal oppression, we demonstrate how art can emphasise and promote women's agency. Tahira's final realisation of the need to establish her selfhood and deflate the definitions of her husband and his family on her body, identity and psyche corroborates the contemporaneity of a feminist narrative. Undoubtedly, Tahira's adherence to and creation of a woman-centric vision of art affirms the triumph of an ordinary Pakistani woman against a patriarchal system that is relentlessly coercive. In a way, the novel thus enlists its significance in the domain of Pakistani women's writing and also aligns with the critical discourses of South Asian literature on female oppression and violence. Thus, the novel symbolises how the patriarchal framework in Pakistan renders the 'room' (un)habitable for women, and we conclude our study by revisiting the observations of Muhammad Ali Jinnah, a barrister, politician and the founder of Pakistan, regarding the predicament of women in his nation:

Notes [1] Honor in its definition is seen to be a virtue, linked with morality, integrity of character, and altruism. This definition has been derived from this article: Deler Singh and Dipali S. Bhandari, 'Legacy of honor and violence: An analysis of factors responsible for honor killings in Afghanistan, Canada, India, and Pakistan as discussed in selected documentaries on real cases,' SAGE Open (Apr. 2021): 1–9, specifically p. 2. doi: 10.1177/21582440211022323. [2] Filomena M. Critelli, 'Between law and custom: Women, family law and marriage in Pakistan,' in Journal of Comparative Family Studies 43(5) (2012): 673–93, specifically p. 675. doi: 10.3138/jcfs.43.5.673. [3] Iftikhar H. Malik, The state and civil society in Pakistan: State and Civil Society in Pakistan Politics of Authority, Ideology and Ethnicity, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1997, p. 68. [4] International Crisis Group, 'Women, violence and conflict in Pakistan,' Asia Report No 265, 8 April 2015, p. 2, online: d2071andvip0wj.cloudfront.net/265-women-violence-and-conflict-in-pakistan.pdf, accessed 18 Dec. 2020. [5] Critelli, 'Between law and custom,' p. 675. [6] Shaheen Sardar Ali, 'Using law for women in Pakistan,' in Gender, Law and Social Justice, ed. Ann Stewart, 139–59, London: Blackstone Press, 2000, [7] International Crisis Group, 'Women, violence and conflict in Pakistan,' p. 2. [8] Syeda Mujeeba Batool and Aisha Anees Malik, 'Bringing the focus back: Aurat march and the regeneration of feminism in Pakistan,' Journal of International Women's Studies 22(9) (2021): 316–30, specifically p. 317. [9] Rubina Saigol, Feminism and the Women's Movement in Pakistan: Actors, Debates and Strategies, Islamabad: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, 2016, online: library.fes.de/pdf-files/bueros/pakistan/12453.pdf, site accessed 17 May 2021. [10] Saigol, Feminism and the Women's Movement in Pakistan, p. 40. [11] Filomena M. Critelli, 'Voices of resistance: Seeking shelter services in Pakistan,' Violence Against Women 18(4) (2012): 437–48, specifically p. 438. doi: 10.1177/1077801212452104. [12] Muhammad Arslan, '#MeToo Pakistani moment: Social media for taboo activism,' SSRN (2019), p. 3, doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3475933, accessed 22 Jun. 2021. [13] Sonia Awan, 'Reflections on Islamisation and the future of the women's rights movement in "Naya" Pakistan,' Angles: New Perspectives on the Anglophone World14 (2022): 1-20, pp. 1–4. doi: 10.4000/angles.5030; Amrita Basu, 'Women, political parties and social movements in South Asia,' Occasional Paper: UN Research Institute for Social Development 5 (2005), online: gsdrc.org/document-library/women-political-parties-and-social-movements-in-south-asia/, accessed 12 March 2021. [14] Batool and Malik, 'Bringing the focus back,' p. 317. [15] Shaheen Sardar Ali, Gender and Human Rights in Islam and International Law: Equal Before Allah, Unequal Before Men? The Hague: Kulwer Law International, 2000. [16] Shari'a encompasses the ordinances derived from the Qur'an (which believers accept as the literal word of God. [17] Lisa Hajjar, 'Religion, state power, and domestic violence in Muslim societies: A framework for comparative analysis,' Law & Social Inquiry 29(1) (2004): 1–38, pp. 4–6, doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4469.2004.tb00329.x. [18] Batool and Malik, 'Bringing the focus back,' p. 318. [19] Amina Jamal, 'Gender, citizenship, and the nation-state in Pakistan: Willful daughters or free citizens?' Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 31(2)(2006): 283–304, specifically p. 283. doi: 10.1086/491676. [20] George Kurian, Cross-Cultural Perspectives of Mate-Selection and Marriage. Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1979; G. Kurian, 'South Asians in Canada,' International Migration 24 (1) (1991): 421–32, specifically p. 427, doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2435.1991.tb01029.x. [21] Arshia U. Zaidi and Muhammad Shuraydi, 'Perceptions of arranged marriages by young Pakistani Muslim women living in a Western society,' Journal of Comparative Family Studies 33(4) (2002): 495–514, specifically p. 496, doi: 10.3138/jcfs.33.4.495. [22] Kalwant Bhopal, 'Education makes you have more say in the way your life goes: Indian women and arranged marriages in the United Kingdom,' British Journal of Sociology of Education 32(3) (2011): 431–47, specifically p. 434, doi: 10.1080/01425692.2011.559342. [23] Karen R. Blaisure and Katherine R. Allen, 'Feminists and the ideology and practice of marital equality,' Journal of Marriage and Family 57(1) (1995): 5–19, specifically p. 6, doi: 10.2307/353812; Myra Marx Ferree, 'Beyond separate spheres: Feminism and family research,' Journal of Marriage and Family 52(4) (1990): 866–84, specifically p. 873, doi: 10.2307/353307. [24] Peter Dodd, 'Family honor and the forces of change in Arab society,' International Journal of Middle East Studies 4 (1973): 40–54; Louise Cainkar, 'Palestinian–American Muslim women: Living on the margins of two worlds,' in Muslim Families in North America, ed. Earle H. Waugh, Sharon M. Abu-Laban and Regula B. Qureshi, 282–307, Alberta: The University of Alberta Press, 1991. [25] Sadia Abbas, The Empty Room, New Delhi: Zubaan, 2018, p. 3. [26] Abbas, The Empty Room, p. 22. [27] Sundari Anitha and Aisha Gill, 'Coercion, consent and the forced marriage debate in the UK,' Feminist Legal Studies 17(2) (2009): 165–84, doi: 10.1007/s10691-009-9119-4; Amrit Wilson, Dreams, Questions, Struggles: South Asian Women in Britain, London: Pluto Press, 2006, pp. 18–22. [28] Aisha K. Gill and Heather Harvey, 'Examining the impact of gender on young people's views of forced marriage in Britain,' Feminist Criminology 12(1) (2017): 72–100, doi: 10.1177/1557085116644774. [29] Abbas, The Empty Room, p. 27. [30] Abbas, The Empty Room, p. 28. [31] Abbas, The Empty Room, p. 32. [32] Rebecca Emerson Dobash and Russell Dobash, Violence Against Wives: A Case Against the Patriarchy, New York: The Free Press, 1979, p. 24. [33] R.W. Connell, Masculinities, Cambridge, MA: Polity Press, 1995, p. 258. [34] Catharine A. MacKinnon, Feminism Unmodified: Discourses on Life and Law, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1987, p. 34. [35] Abbas, The Empty Room, p. 10. [36] Abbas, The Empty Room, p. 30. [37] Abbas, The Empty Room, p. 30. [38] Ti-Grace Atkinson, Amazon Odyssey, New York: Links Book, 1974, p. 14. [39] Adrienne Rich, 'Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence,' in Desire: The Politics of Sexuality, ed. Ann Barr Snitow, Christine Stansell and Sharon Thompson, 212–41, London: Virago, 1984. [40] Shulamith Firestone, The Dialect of Sex: The Case for Feminist Revolution, New York, NY: William Morrow and Company, 1970, p. 157. [41] Firestone, The Dialect of Sex, p. 152. [42] Firestone, The Dialect of Sex, p. 157. [43] Abbas, The Empty Room, p. 31. [44] Abbas, The Empty Room, p. 32. [45] Atkinson, Amazon Odyssey, p. 16. [46] Abbas, The Empty Room, p. 34. [47] Abbas, The Empty Room, p. 70. [48] Critelli, 'Between Law and Custom,' p. 673. [49] Evelyn Nakano Glenn, 'Gender and the family,' in Analyzing Gender: A Handbook of Social Science Research, ed. Beth B. Hess and Myra Marx Ferree, 348–80, Newbury Park, CA: Sage, 1987. [50] Shireen Quadri, 'Sadia Abbas: Mapping misogyny', the punch magazine (December 2019), online: thepunchmagazine.com/the-byword/interviews/sadia-abbas-mapping misogyny, accessed 16 Jun. 2021. [51] Pamela M. Fishman, 'Interaction: The work women do,' in Language, Gender, and Society, ed. Barrie Thorne, Cheris Kramarae and Nancy Henley, 89–101, Rowley, MA: Newbury House, 1983; Linda Thomson and Alexis J. Walker, 'Gender in families: Women and men in marriage, work, and parenthood,' Journal of Marriage and Family 51(4) (1989): 845–71, doi: 10.2307/353201. [52] Andreas Nordin, 'Altruism or mutualism in the explanation of honour with reference to reputation and indirect reciprocity?' Sociology and Anthropology 4(2) (2016): 125–33, specifically p. 130, doi: 10.13189/sa.2016.040210. [53] Judith Butler, Frames of War: When Is Life Grievable? London: Verso, 2009, p. 14. [54] Abbas, The Empty Room, p. 24. [55] Abbas, The Empty Room, p. 36. [56] Sunita Mahtani Stewart, Michael H. Bond, L. M. Ho, Riffat Moazam Zaman, Rabiya Dar and Muhammad Anwar, 'Perceptions of parent and adolescent outcomes in Pakistan,' British Journal of Developmental Psychology 18(3) (2000): 335–52, specifically p. 342, doi: 10.1348/026151000165733. [57] Abbas, The Empty Room, p. 36. [58] Judith Butler, 'Performativity, precarity and sexual politics,' AIBR. Revista de Antropología Iberoamericana 4(3) (2009): i–xiii, specifically p. ii, online: www.aibr.org/antropologia/04v03/criticos/040301b.pdf, accessed 12 Jul. 2022. [59] Unaiza Niaz, 'Women's mental health in Pakistan,' World Psychiatry 3(1) (2004): 60–62, specifically p. 60, online: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1414670/, accessed 12 Jul. 2022. [60] Abbas, The Empty Room, p. 83. [61] Isabell Lorey, State of Insecurity: Government of the Precarious, translated by Aileen Derieg, London: Verso, 2015, p. 12. [62] Lorey, State of Insecurity, p. 21. [63] Purna Sen, 'Crimes of honour,' in Value and Meaning, ed. Lynn Welchman and Sara Hossain, 42–63, specifically p. 52, London: Zed Books, 2005. [64] Shaheen Sardar Ali, 'Using law for women in Pakistan,' in Gender, Law and Social Justice, ed. Ann Stewart, 139–59, specifically p. 147, London: Blackstone Press, 2000. [65] F. Bari, 'Country briefing paper: Women in Pakistan,' Asian Development Bank (July 2000): 1–58, specifically p. 42, online: www.adb.org/sites/default/files/institutional-document/32562/women-pakistan.pdf, site accessed 14 Oct. 2021. [66] Bari, 'Country briefing paper,' p. 38; Khawar Mumtaz and Farida Shaheed (eds), Women of Pakistan: Two Steps Forward, One Step Back, London: Zed Books, 1987, p. 12. [67] Gayle Rubin, 1975. 'The traffic in women: Notes on the "political economy" of sex,' in Toward an Anthropology of Women, ed. Rayna R. Reiter, 157–210, specifically p. 175, New York and London: Monthly Review Press, 1975. [68] Abbas, The Empty Room, p. 83. [69] Akbar S. Ahmad, Pakistan Society: Islam, Ethnicity and Leadership in South Asia, Karachi: Oxford University Press, 1986, p. 33. [70] Ahmad, Pakistan Society, p. 33. [71] Unaiza Niaz, 'Violence against women in South Asian Countries,' Archives of Women's Mental Health 6(3) (2003): 173–84, specifically p. 180, doi: 10.1007/s00737-003-0171-9. [72] Niaz, 'Violence against women,' p. 180. [73] Ilyas Mirza and Rachel Jenkins, 'Risk factors, prevalence, and treatment of anxiety and depressive disorders in Pakistan: systematic review,' BMJ 328(7443) (2004): 794, doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7443.794. [74] Farah Qadir, Amna Khalid, Sabahat Haqqani, Zill-e-Huma and Girmay Medhin, 'The association of marital relationship and perceived social support with mental health of women in Pakistan,' BMC Public Health 13(1150) (2013): 1–13, specifically p. 3, doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-1150. [75] Linda Thompson and Alex J. Walker, 'Gender in families: Women and men in marriage, work, and parenthood,' Journal of Marriage and Family 51(4) (1989): 845–71, specifically p. 852, doi: 10.2307/353201. [76] Israel W. Charny and Snan Parnass, 'The impact of extramarital relationships on the continuation of marriages,' Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy 21(2) (1995): 100–15, specifically pp. 100–101, doi: 10.1080/00926239508404389. [77] Abbas, The Empty Room, p. 92. [78] Abbas, The Empty Room, p. 74. [79] Abbas, The Empty Room, p. 74. [80] Abbas, The Empty Room, p. 74. [81] Kumaralingam Amirthalingam, 'Women's rights, international norms, and domestic violence: Asian perspectives,' Human Rights Quarterly 27(2) (2005): 683–708, specifically p. 684, doi: 10.1353/hrq.2005.0013. [82] Amirthalingam, 'Women's rights, international norms, and domestic violence,' p. 697. [83] Abbas, The Empty Room, p. 184. [84] Carole Pateman, The Sexual Contract, Cambridge: Polity Press, 1988. [85] Heidi Hartmann, 'Capitalism, patriarchy, and job segregation by sex,' in Capitalist Patriarchy and the Case for Socialist Feminism, ed. Zillah R. Eisenstein, 206–47, specifically p. 208, New York, NY: Monthly Review Press, 1979. [86] Nicola Barker, The Evolution of Marriage and Relationship Recognition in Western Jurisdictions, New York, NY: UN Women, 2018, p. 8. [87] Marilyn Friedman, 'Autonomy, social disruption, and women,' in Relational Autonomy: Feminist Perspectives on Autonomy, Agency, and the Social Self, ed. Catriona Mackenzie and Natalie Stoljar, 35–51, specifically p. 37, New York: Oxford University Press, 2000. [88] Theresa Van Lith, Patricia Fenner and Margot Schofield, 'The lived experience of art making as a companion to the mental health recovery process,' Disability and Rehabilitation 33(1) (2011): 652–60, specifically pp. 652–56, doi: 10.3109/09638288.2010.505998. [89] Abbas, The Empty Room, p. 194. [90] Abbas, The Empty Room, p. 244. [91] Oscar Wilde, 'The Critic as Artist,' in The Artist as Critic: Critical Writings of Oscar Wilde, ed. Richard Ellmann, 340–408, specifically p. 389, New York, NY: Random House, 1986. [92] Heather L. Stuckey and Jeremy Nobel, 'The connection between art, healing, and public health: A review of current literature,' American Journal of Public Health 100(2) (2010): 254–63, specifically p. 254, doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.156497. [93] Abbas, The Empty Room, p. 253. [94] Jean Grimshaw, 'Autonomy and identity in feminist thinking,' in Feminist Perspectives in Philosophy, ed. Morwenna Griffiths and Margaret Whitford, 90–108, specifically p. 105, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1988. [95] John Graham-Pole, Illness and the Art of Creative Self-Expression, Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications, 2000, p. 32. [96] Paul M. Camic, 'Playing in the mud: Health psychology, the arts and creative approaches to health care,' Journal of Health Psychology 13(2) (2008): 287–98, specifically p. 293. doi: 10.1177/1359105307086698. [97] Abbas, The Empty Room, p. 314. [98] Abbas, The Empty Room, p. 316. [99] Ann Rosalind Jones, 'Writing the body: Toward an understanding of "L'Ecriture Feminine",' Feminist Studies 7(2) (1981): 247–63, specifically p. 251, doi: https://doi.org/10.2307/3177523. [100] Hélène Cixous, Keith Cohen and Paula Cohen, 'The laugh of the Medusa,' Signs 1(4) (1976): 875–93, specifically p. 875, doi: 10.1086/493306. [101] Ellen Dissanayake, What is Art For? Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press, 1988, p. 157. [102] Deniz Kandiyoti, 'Bargaining with patriarchy,' Gender and Society 2(3) (1988): 274–90, specifically p. 278, doi: 10.1177/089124388002003004. [103] Niaz, 'Violence against women,' p. 178. [104] Tanya D'Lima, Jennifer L. Solotaroff and Rohini Prabha Pande, 'For the sake of family and tradition: Honour killings in India and Pakistan,' ANTYAJAA: Indian Journal of Women and Social Change 5(1) (2020): 22–39, specifically p. 24, doi: 10.1177/2455632719880852. [105] Nasreen Akhtar and Daniel A. Metraux, 'Pakistan is a dangerous and insecure place for women,' International Journal on World Peace 30(2) (2013): 35–70, specifically p. 36. [106] Akhtar and Metraux, 'Pakistan is a dangerous and insecure place for women,' p. 36. [107] Sanchita Bhattacharya, 'Status of women in Pakistan,' Journal of the Research Society of Pakistan 51(1) (2014): 179–211, specifically p. 186, online: pu.edu.pk/images/journal/history/PDF-FILES/7v51_No1_14.pdf, accessed 12 Jul. 2022. [108] Muhammad Ali Jinnah, 'Speech at a meeting of the Muslim University Union,' Aligarh (10 March 1944), quotepark.com, online: quotepark.com/quotes/1938147-muhammad-ali-jinnah-no-nation-can-rise-to-the-height-of-glory-unless-y/, accessed Feb. 2022. |

|